Geoffrey M. Hodgson

‘This is a thundering good read’ – Peter Smith

‘The best article I’ve read for a while’ – Karen Bradley

‘Brilliant on why socialism isn’t “obvious”’ – Robbie Hudson

‘Very informative & sobering. Highly recommended’ – Jan Davies

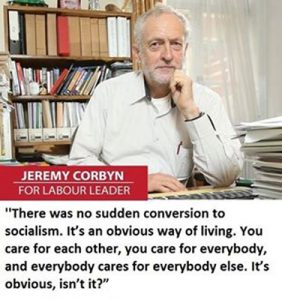

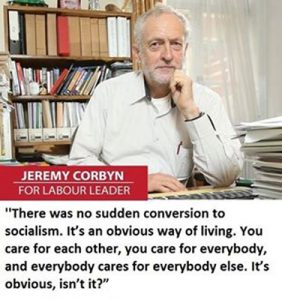

One thing in British politics is very obvious: Jeremy Corbyn and his followers are very keen on something they call socialism. But this word has migrated in meaning since it first appeared in English in 1827. So it is reasonable to ask what they mean by it.

I’ve tried. I got lots of vague answers.

I fully appreciate that the Mirror is an unsuitable forum for a detailed account of the workings of the future socialist utopia, but unfortunately I have little else to go on. Apart from some gestures in favour of nationalization, and some sentimentality for the pre-Blair version of Labour’s Clause Four, I can find no fuller account of what Corbyn’s ‘socialism’ means.

Yet we are told twice (in one short quote) that it is ‘obvious’.

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me.

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me.

My comrades and I saw these deformations as unfortunate results of Stalinist bureaucracy plus Western hostility. We believed that a different, ‘democratic socialism’, was possible.

What persuaded me that socialism is not ‘obvious’ was a consideration of how such a system could work, in detail and in practice. How would production and distribution be organised? How would dispersed information concerning production and distribution be gathered and processed? How would resources be allocated? Who would decide? How would trillions of dispersed decisions be somehow processed by democratic committees? How would less-devoted workers be incentivized or persuaded to work harder or with greater attention to detail? What incentives would exist to encourage innovation and change, especially when everything had to be referred to some democratic council? And so on.

Once you begin to ask these difficult questions, socialism becomes much less ‘obvious’.

Numbers and incentives

Some version of socialism might work on a small scale. Cooperation can work in small groups, based on close, inter-personal interactions. Humans have co-operated in this way, in families and tribal units, for many thousands of years.

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Their small size allows participants to monitor each other, to ensure that necessary tasks are carried out and that the interests of the community are served.

Enforcement mechanisms range from praise to punishment. Within these relatively small and cohesive groups, trust and targeted sanctions are mechanisms for encouraging cooperation, reciprocity and compliance with social rules.

But these mechanisms depend on a degree of familiarity with one another. Big problems emerge when we move from tribal to large-scale societies. These began to develop about twelve thousand years ago. Our natural and cultural dispositions to cooperate and to help one another had to be supplemented by other mechanisms.

In larger societies, face-to-face, trust-based mechanisms to sustain cooperation are relatively less effective. When we move from communities of a hundred or so, where it is possible for everyone to know everyone else, to communities of thousands or more, then interpersonal trust and reputation are much less successful with large-scale interactions, and they have to be supplement by other incentives and constraints.

The increase of scale can create incentive problems that can be overcome in smaller communities. Many socialist experiments involved collectivisation. But when thousands of people are brought together, and rewards are shared, then there is less incentive to make the extra effort, because the rewards from that additional work would be hugely diluted.

This problem was illustrated dramatically in China. After the Communist Revolution of 1949, agriculture was organized into large collective farms. Farmers had little incentive to improve productivity, other than by threats and bureaucratic bullying. Risky innovation was unwise. Productivity remained low and often there were shortages of food.

Mao Zedong died in 1976, opening up the possibility of reform. In 1978 some peasant farmers decided to withdraw from collective farms and take responsibility for production at the household level, where the household (instead of the collective) received the revenue from its sold output. Individual households had much greater incentives to work harder and to innovate.

After decades of slow growth under Mao, China’s explosive economic growth began with those changes in rural areas. As a result, unprecedented millions were lifted out of poverty. China’s spectacular economic growth began when agriculture began to pass into the private control of the peasants after 1978.

|

This book by G. M. Hodgson elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

|

While interpersonal interactions can engender cooperation on a small scale, and they continue to do so in families and small communities, in large-scale societies other mechanisms and incentives are necessary. Economic history teaches us that modern dynamic economies depend on markets, competition and a large private sector, as well as an effective state.

Corbyn is right: it is very important that we care for one another. But in terms of practical input, we cannot care equally for everyone. We can care more readily for those close to us, who we know well: our family, our friends and our workmates. But extending our caring to society as a whole becomes more of a political and less of a personal project. We need caring governments, but the practical extension of caring from the personal to the political is neither obvious nor easy.

Corbyn is right: it is very important that we care for one another. But in terms of practical input, we cannot care equally for everyone. We can care more readily for those close to us, who we know well: our family, our friends and our workmates. But extending our caring to society as a whole becomes more of a political and less of a personal project. We need caring governments, but the practical extension of caring from the personal to the political is neither obvious nor easy.

The need for countervailing power

A simplistic response would be to suggest that we elect a government that is staffed by well-meaning individuals. But to different degrees, almost everyone is corruptible. Even the uncorrupt have their own biased agendas and priorities.

There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail.

There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail.

Even if politicians are competent and well meaning – lots of them are – they still face the problems of dispersed knowledge and uncertainty in modern, large-scale, and highly complex economies.

Consequently, relatively little can be planned from the top. Solutions to real-world, nitty-gritty problems are rarely ‘obvious’. There is a need for both humility and experimentation. We need to try and see what works and learn from mistakes, rather that rushing headlong towards what seems obvious.

The survival of democracy depends on a dispersion of real economic and political power. A healthy, pluralist polity depends on a pluralist economy, with multiple centres of autonomous decision-making. This means a system of private enterprise, as well as a political system with checks, balances and power that can be held to account. The state can and must also play a vital role in the economy, but not to the extent that it smothers private enterprise and initiative.

There is a large and fascinating analytical literature on the problems involved in classical socialism, and I cite a few works on this below. There is not the space to go into it further here. These works are not all written by neoliberals. But intelligent neoliberals – despite their limitations – are often worth reading. Although there are disagreements on approach and detail, the general conclusion is that large-scale socialism cannot work effectively and democratically. This analytical conclusion is corroborated by the historical experience of stagnation in innovation in Soviet-style regimes.1

The ‘obvious’ roots of fanaticism and intolerance

The ‘obviousness’ of socialism empowers its supporters with enduring energy and even fanaticism. If socialism is ‘obvious’, how do we explain the failure of other intelligent people to get on board? If they are not stupid, then they must be acting out of personal malice or greed. They must have sold out their principles in some way. Or they are just plain nasty. When socialism is seen as ‘obvious’, its opponents are regarded as stupid or evil.

The perceived ‘obviousness’ of socialism fuels both fanaticism and intolerance. Because the solution to the problem is ‘obvious’, there can be no doubt. There is no need to experiment, to seek wise counsel, or to listen to critics. Those that deny the obvious are deluded, corrupted, or in the pay of those that gain from the existing system.

The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said:

The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said:

‘What is objectionable, what is dangerous about extremists is not that they are extreme, but that they are intolerant. The evil is not what they say about their cause, but what they say about their opponents.’

We have seen this elsewhere, in the brutal fanaticism of religious zealots, as well as in the murderous tragedies of twentieth-century socialism under Stalin and Mao. They all shared in common the absence of doubt, the certainty of redemption or victory, and the confidence in their own righteousness.

It is deeply saddening that the once-great British Labour Party has been taken over by people who think that their aims and long-term solutions are ‘obvious’. Once the zealots take over, there is no way back. The party is then trapped in a vicious circle.

A diminished vote in an election is a success because it is seen as a big vote for a purer socialism. When Labour lost the 1983 election on a socialist manifesto, with the lowest share of the vote since 1918, Tony Benn greeted the result as a triumph for socialist ideas.

Even small successes – such as winning elections to parish councils – feed frenzies of celebration. All acknowledged failures are blamed on others, such as the ‘mainstream media’ or the ‘traitors’ within.

Even small successes – such as winning elections to parish councils – feed frenzies of celebration. All acknowledged failures are blamed on others, such as the ‘mainstream media’ or the ‘traitors’ within.

With an ideology where no possible event can falsify the ‘obvious’, the doubters are purged. The wise give up. The fanatics win.2

Touting socialism as an ‘obvious’ solution empowers a fanaticism that can crush all traces of liberal tolerance, which is essential for democracy within any political party, as well as within the political system as a whole. Corbyn’s victory in the 2016 leadership election marks the point of no return for Labour. It is beyond the beginning of the end. Labour is now dying. Thoughtful radicals must go elsewhere.

10 August 2016

Minor edits – 11-13 August 2016

A version of this post was published in the i newspaper on 11 August.

More comments on this post:

‘A gloomy but sadly very acute and perceptive analysis’ – Helen Salmon

‘Definitely one of his best, and the best thing I’ve read all week’ – Tom Atkinson

‘Excellent article on the anti-democratic nature of seeing one’s views as “obvious”’ – Francis Hoar

‘Brilliant piece on why “obvious” socialism leads to intolerance (and doesn’t work either)’ – Colin Talbot

‘Thank you so much for your still small voice of reason: it is worth its weight in gold amid this chaos’ – Elizabeth Jones

End Notes

- A recent contribution of mine on the socialist calculation debate can be found here.

- After publication, Colin Williams kindly pointed out that the Russell quote that heads this post – although widely attributed to him and close to other similar quotes by Russell – cannot be found in this exact form in Russell’s works.

Bibliography

Hayek, Friedrich A. (1944) The Road to Serfdom (London: George Routledge).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Lavoie, Donald (1985) Rivalry and Central Planning: The Socialist Calculation Debate Reconsidered (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Mill, John Stuart (1859) On Liberty (London: John Parker & Son).

Nove, Alexander (1991) The Economics of Feasible Socialism Revisited (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Ostrom, Elinor (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Steele, David Ramsay (1992) From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court).

Zhou, Kate Xiao (1996) How the Farmers Changed China (Boulder, CO: Westview Press).

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me.

Here is my own confession: fifty years ago I believed that socialism was ‘obvious’. Eventually I was persuaded otherwise. Initially, it was not my growing awareness of the horrendous consequences of the socialist experiments in Russia, China and elsewhere that jolted me. Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom studied the management of common-pool resources – such as medieval common land, fisheries or agricultural irrigation schemes – and showed how they can be effectively managed by relatively small local communities.

Corbyn is right:

Corbyn is right:  There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail.

There is a need for rules, monitoring and countervailing power. If all economic power is concentrated in the bureaucracy of planners, then will be no effective alternative power that can countervail. The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said:

The great American politician Robert F. Kennedy once said: Even small successes –

Even small successes –

An excellent piece which will resonate with anyone who has had a run in with a Corbynista. Its worth saying that the complete lack of detail in Corbyn’s vision makes it easy for his fans to project their own fantasies onto him. All the Corbynistas will have a different vision of this future utopia but they will never find out just how different these visions are because there is never any discussion of any substance.

Excellent piece.

Bibliography is a treasure trove of necessary reading for all.

Themes outlined also applicable to the SNP support here in Scotland – independence is the ‘obvious’ solution to all problems and fanatics consider you stupid or a tory (which to many, without reasoned argument why, simply means evil).

As William Beveridge said: “Organisation of social insurance should be treated as one part only of a comprehensive policy of social progress. Social insurance fully developed may provide income security; it is an attack upon Want. But Want is one only of five giants on the road of reconstruction and in some ways the easiest to attack. The others are Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness.”

It never surprises me that the left always manage to avoid talking about idleness.

Just brilliant

Interesting to see Alex Nove’ “Economics of Feasible Socialism” among your sources. That was the book that finally killed off my youthful attachment to the socialist cause.

As an appreciative reader of Geoffrey Hodgson’s work on institutional economics, I’m disappointed that he is either ignorant (or pretending to be ignorant) of the distinctions between Stalinism and communism, communism and socialism, and socialism and market socialism. And no-one in their right mind can believe that Corbyn is imagining 1960s communism. Why such an otherwise intelligent author has written such a posturing, straw man piece is beyond me…

I do not say that Corbyn is ‘imagining 1960s communism’. I am in my right mind. And I am not, at least pretending, to be ignorant.

Historically, of course, Marx and Engels often used the term ‘communism’ instead of ‘socialism’. But this was primarily to distance themselves from the analytic, strategic and tactical ideas of contemporary socialists rather than to postulate a radically different objective. For them, ‘communism’ was more a label for their movement, rather than their goal. Thus in about 1845 they wrote: ‘Communism is not for us a state of affairs which is to be established, an ideal to which reality [will] have to adjust itself. We call communism the real movement which abolishes the present state of things.’

It was only with the Bolshevik Revolution that ‘socialism’ came to refer to a distinct stage between capitalism and communism. In 1917 Lenin in his State and Revolution introduced this usage, partly to help defend the planned Bolshevik seizure of power against the criticism that Russia was insufficiently developed for socialist revolution. By contrast, Marx and Engels did not use the term socialism to refer to a future stage between capitalism and communism.

So it could be said that socialists are communists. It depends on how these terms are defined.

In addition there is Communism with a capital ‘C’, which might be used to refer to regimes run by Communist Parties, whether or not they can be better described as socialist, fascist, imperialist, capitalist, or whatever.

I discuss some of the problems with the meaning of the term ‘market socialism’ in my 1999 Economics and Utopia book. Socialists rarely embraced markets until after 1945.

A problem is that Corbyn does not clearly define what he means by socialism. It has become a near-empty shibboleth. Yet every prominent Labour member seems to want to claim allegiance to it, whatever it means. Rather than falsely accusing me of ‘imagining’ Corbyn’s own view, you should seek clarification from him.

Thanks for the reply. For the record, wasn’t suggesting you were not in your right mind – I am puzzled by the article precisely because the opposite is the case..

I suppose my issue then is that you appear to be presuming a negative conclusion when in fact the substantive basis for that is merely an absence of information. To put my view differently then: I cannot see why anyone would presume that the socialism Corbyn refers to – even in the vague terms you mention – would suffer from the problems you raise. His policy positions, for example, are not based on an overthrow of existing institutions but rather progressive changes to the status quo. That being the case I can’t really see the justification for the negative tone you adopt.

If the issue is that Corbyn needs to explicate his ‘vision’ further, why not just say so sans the tone of doom?

Again, you miss the key arguments that I am trying to make. Let me summarise in five points.

1. I first propose that Corbyn is not very clear about what ‘socialism’ means, although he is very keen on it. If it is defined in terms of common ownership (and that is unclear in his statements), then, because he is vague, it could mean anything from 100% to (say) 10% common ownership.

2. I note also that Corbyn repeats that socialism (whatever it means) is ‘obvious’. Even if it simply involves ‘progressive changes to the status quo’ (as you put it), then these changes are seen as ‘obvious’. From this I draw two further sets of observations.

3. Practical considerations of how some sort of ‘socialist’ society would work, as traditionally defined, or in moderation, reveal complex problems whose solutions are far from ‘obvious’.

4. The belief that your aims are ‘obvious’ (whatever those aims are) raises questions among the committed as to why many other people fail to support them. This fuels the conclusion that opponents are either stupid or evil, as I explain in the last part of my essay.

5. In response to your last question, Corbyn not only has to explain his ‘vision’ further, but also he has to get into the practical detail of how it would operate. If and when he does, then he will realise that such solutions are far from ‘obvious’ and call upon his followers to stop treating all critics like evil agents of capitalism.

On one level I would agree with much of this, but in a broader context I don’t think it takes us very far since the problem with much of the left is not that they haven’t listened to neoliberal critiques; on the contrary they have accepted too much of them. One result is that Corbyn’s critics have quite failed to articulate a winning alternative policy package.

Rather than focusing on Corbyn’s vague remarks, one might examine the economic policies proposed by McDonnell. Whatever one thinks of their merits, in the highly improbable event of Labour winning the next election they would not lead to totalitarianism. The checks and balances of a modern democracy would ensure that, if nothing else. There have been post-war conceptions of democratic socialism that when put into practice have led to general prosperity and liberty, not tyranny. Governments proclaiming themselves to be socialist have come to power through democratic means; this happened in Western European countries in the post-war period. In the Nordics and elsewhere this did not lead to totalitarianism. On the contrary, these were prosperous societies with some of strongest individual rights in the world. They were also egalitarian. In varying ways they had strong state involvement (it has even been suggested that c.1980 Austria had a higher degree of public ownership than its then communist neighbour Yugoslavia). However one wishes to define socialism this matters because this, rather than Stalin’s Russia or Mao’s China, is what a Labour government might do. And this experience matters because contra Hayek it did not lead to totalitarianism. Hayek’s ‘Road to Serfdom’ is a slippery slope argument and, like many slippery slope arguments, it is wrong. Hayek wrote it in the context of Attlee’s Labour Party, he was not just arguing that Bolshevism must end in tyranny but experiments in democratic socialism too. The state intervention of Attlee’s government led to the NHS and the welfare state, not in.

The neo-liberal approach is not even particularly useful in the context of the communist experience. It is certainly the case that China’s post-Mao growth started with liberalisation, but this was not the sort of policy approach neo-liberals advocated. The Chinese path was gradualist with, to this day, weak property rights. The neo-liberal approach was for shock therapy, tried elsewhere with mixed results to say the least (http://www.theglobalist.com/for-whom-the-wall-fell-a-balance-sheet-of-the-transition-to-capitalism/) . Further, neo-liberal own attitudes to democracy are distinctly ambivalent. This is not just seen in notorious cases such as Hayek et al supporting Pinochet; German ordoliberalism and the Italian ‘Bocconi boys’ have led to the Eurozone operating under structures designed to bypass democratic power and to heavily circumscribe the policies elected governments can pursue.

This matters because, as I have said here before, the centre left has largely failed to address the situation we are now in. Almost eight years after the financial crisis incomes continue to stagnate for large swathes of the workforce in Western economies with particularly poor prospects for younger people (https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jul/14/up-to-70-per-cent-people-developed-countries-seen-income-stagnate). Austerity continues to hold back economies – not least in Europe from the embedded neo-liberal rules – despite historically low interest rates. Inequality has reached levels beyond those that could be justified in terms of incentives. Many rather moderate commentators have been making these points – witness the unlikely spectacle of Jeffrey Sachs, from architect of the Russian privatisation programme to Bernie Sanders supporter! In the face of current challenges states need to spend more and in key areas like finance and the environment they need to intervene more.

Since Corbyn became leader there has been a barrage of comments pointing out his failings as a leader and the weaknesses of his policies. As it happens, I agree with a good deal of this (but far from all of it). As a strategy for changing Labour members’ minds it has been an utter failure (and, for better or worse, it is Labour Party members who choose the leader). Calling people dupes, fools, entryists, thugs and the rest is not likely to change their minds. There needs to be bold and imaginative thinking on the left to address contemporary problems; if Corbyn is not the answer (and electorally he clearly isn’t) there needs to be a credible alternative and the centre left of Labour have singularly failed to articulate one. Philip Mirowski cheekily echoes Hayek in dedicating his ‘Never Let a Serious Crisis: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown’ to ‘neoliberals of all parties’. Traditional left parties across Europe are in crisis – it’s not just Labour – in part because they have accepted much of neo-liberalism (going along, for example, with Euro Zone rules).

It is also worth remarking that it would be easy to find similar statements to Corbyn’s amongst leading Greens. In British political discourse people tend to be fairly nice if patronising to Greens, rather than claiming the logic of their policies would lead to tyranny. Elsewhere though key sections of the right are promoting climate change denial – in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence – precisely because they regard global warming as a Trojan horse for forms of state intervention they thought they had banished. On both sides of the Atlantic Greens have been denounced in these terms (e.g. see this from former Czech premier Vaclav Klaus http://www.klaus.cz/clanky/1206) . Saying Corbyn’s or anyone else’s ideas would, if pushed, lead to tyranny is ultimately not particularly helpful here.

I would like to take up one of the questions asked about how socialism might work in practice: “How would trillions of dispersed decisions be somehow processed by democratic committees?”

The answer is firstly much as they are now. Individuals, businesses and public bodies have to make many decisions on prices, wages, contracts, purchases etc. I would envisage a greater role for elected bodies at local and national level and within industrial co-operatives, but otherwise the process would be similar.

In the longer term many more decisions could be made by direct public vote, which would require advanced technology. This would allow voters to directly set tax rates, benefit levels and public expenditure in various categories.

Thanks for your comment.

Socialism (as classically defined) does not imply that decisions are made “much as they are now”.

Private enterprises under capitalism have rights of autonomy and contract that would not be granted to workplaces within (say) a state-owned enterprise. In a state-owned enterprise decisions and responsibilities lie ultimately with the national board, or the government. The establishment of private enterprise and markets is a necessary condition to allow genuine devolution of much decision-making. The literature on the socialist calculation debate is very clear on all these points.

Some decisions could be made by public vote, using modern information technology. But there are practical limits to the number of decisions that can be made.

Some people may also wonder whether it is a good idea to put as much as possible to the vote, especially give the experience of recent referendums in the UK! There is something to be said for representative rather than direct democracy.

Pingback: Conversations with Corbynites | Commonly understood as [a blawg]

Pingback: The Perils of Corbynista Populism – New Politics

Pingback: Our resurgent enemy: authoritarian nationalism trumps neoliberalism – New Politics

Pingback: What might have happened if Tony Blair had introduced electoral reform? – New Politics

Pingback: From Russia to Venezuela: a century of useful idiocy – New Politics

Pingback: The Levellers were liberal democrats – not socialists – New Politics

Pingback: Socialism has invaded the moral high ground – New Politics

Pingback: 200 Years of Karl Marx – New Politics

Pingback: Brexit, Nationalism and Empire – New Politics