Category: Tony Benn

October 11th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

If you wish to cultivate an image of being principled and politically pure, then avoidance of policy details, plus a good dose of historical ignorance, can be very useful. You may conjure up figures from past history and recruit them to the cause of your choice.

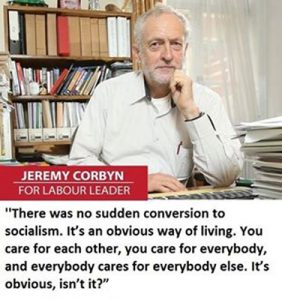

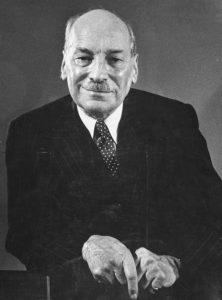

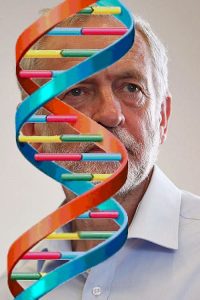

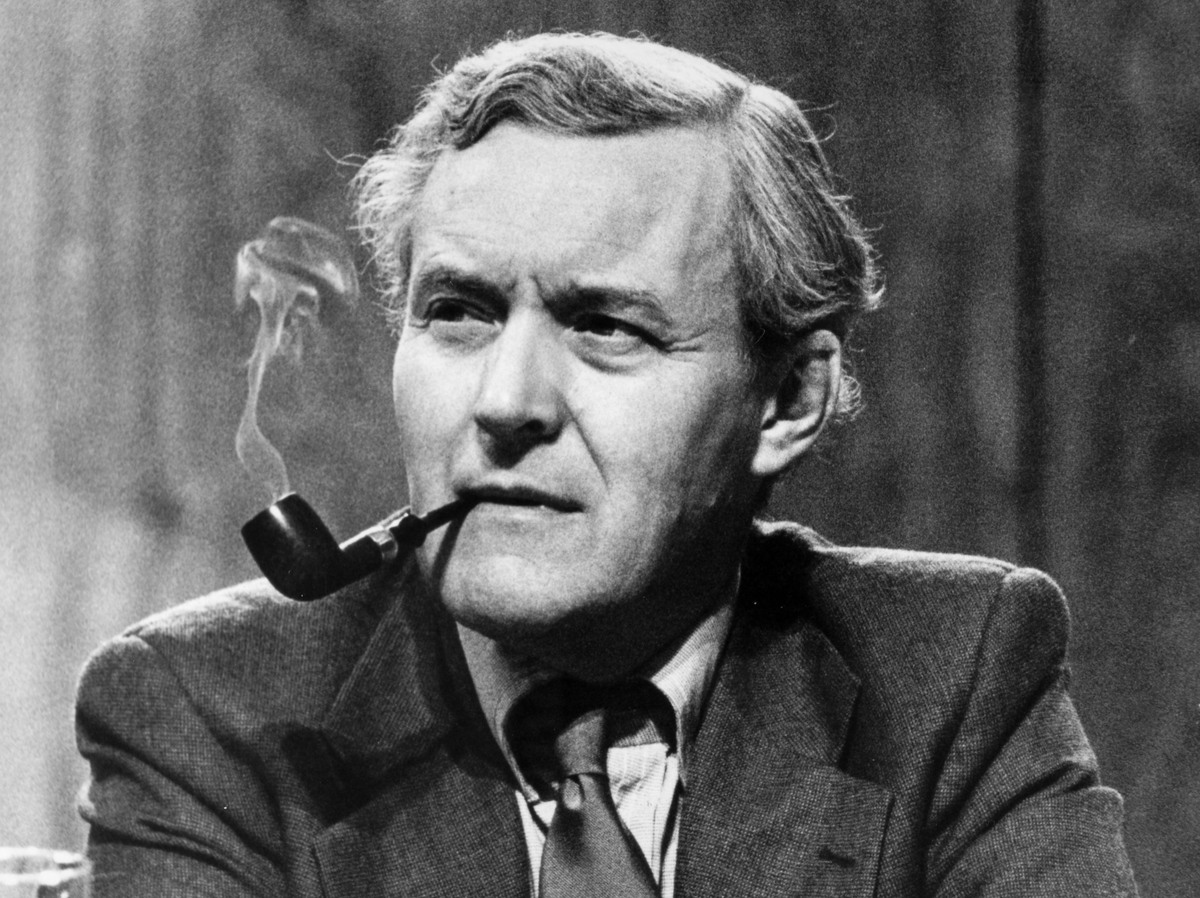

Perhaps unwittingly, Jeremy Corbyn acquired these methods from his mentor Tony Benn. Their shared cause, or course, is socialism. But its details must be kept vague and the statist pill must be sugared with ample use of the word “democratic”. Not too much thought must be applied to how the “democratic” bit works in practice.

Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn

Ignorance of history is an asset. You find some radical heroes who have opposed injustice, inequality, and the status quo. Don’t go into too many details. It might prove embarrassing. Simply suggest that because of their radical energy these radicals must have been, or they were on the way to becoming, “democratic socialists”.

It’s even better if you can go back in history long before there was any movement calling itself socialist – long before the word was invented. Then you can do a bit of hand-waving with phrases like “their ideas were moving towards democratic socialism” or “what would they think today?” with less fear of contradiction.

After all, if they were true and principled radicals, then they must have been moving in that direction. Socialism is obvious. Isn’t it?

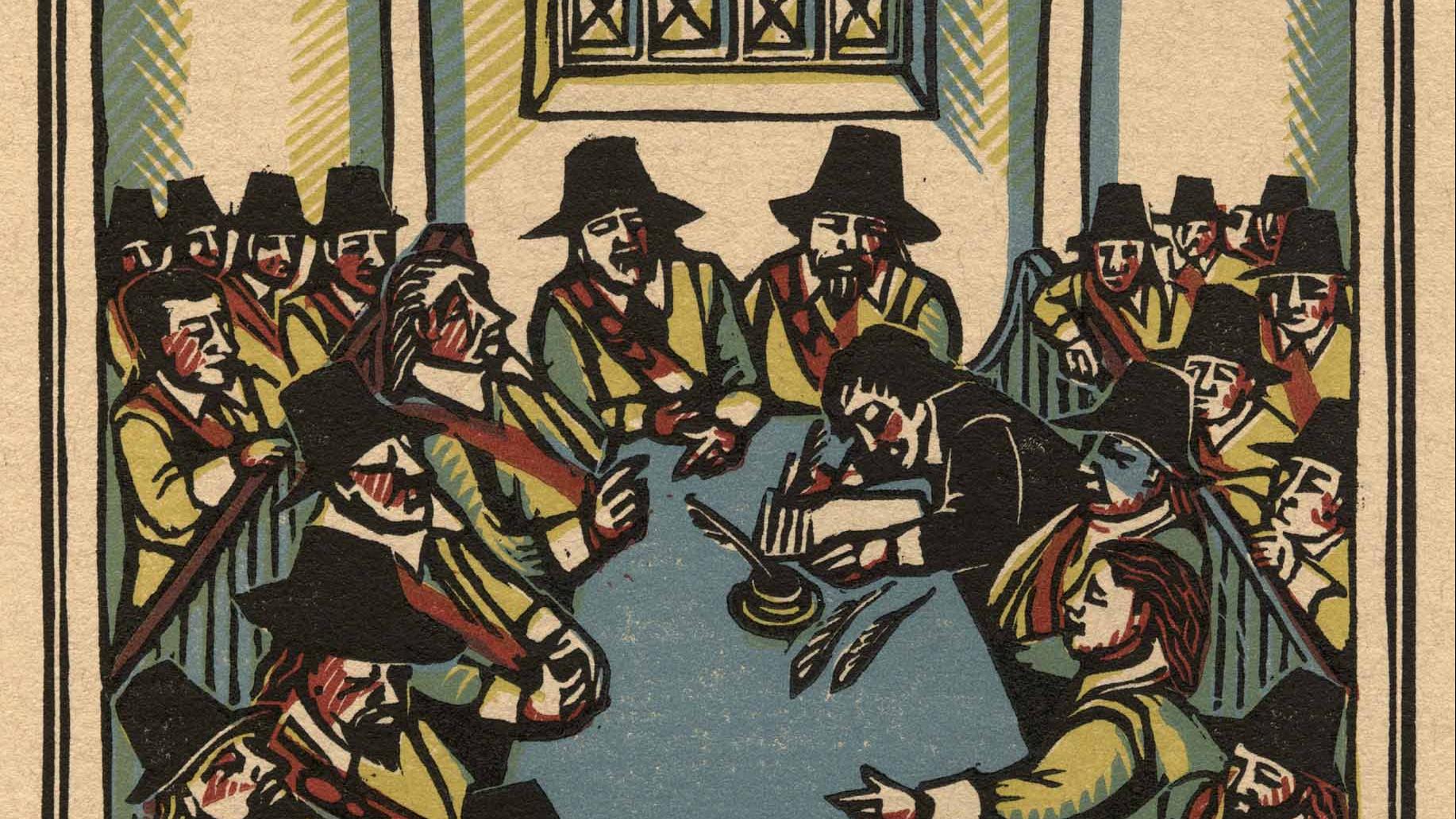

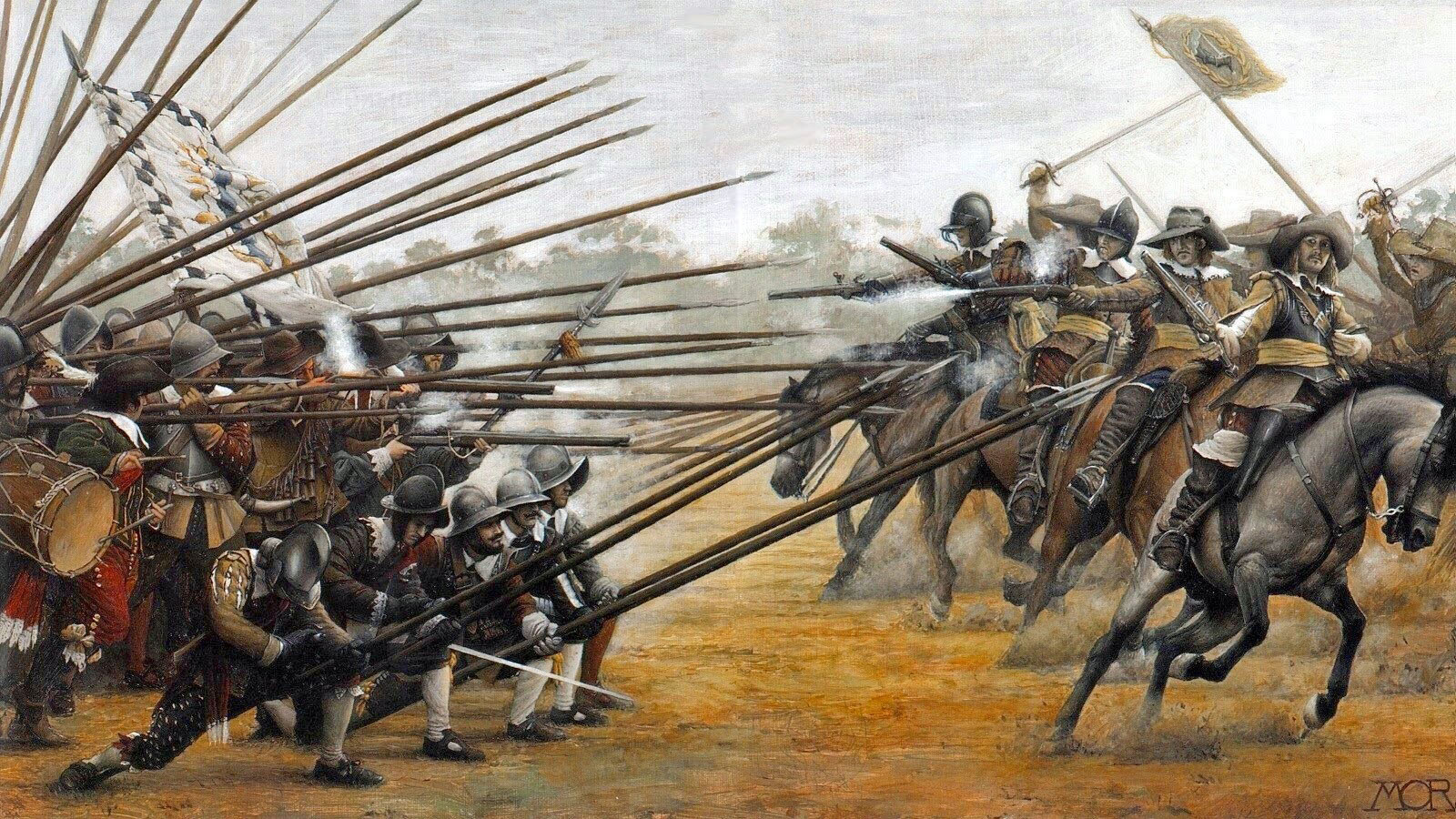

The English Civil War

The English Civil War of the 1640s is a good hunting ground for your heroes. In a book published in 1980, the veteran Labour Party MP Fenner Brockway declared the seventeenth-century Levellers and Diggers as Britain’s First Socialists. His friend Tony Benn had already located them there. Jeremy Corbyn followed their cue.

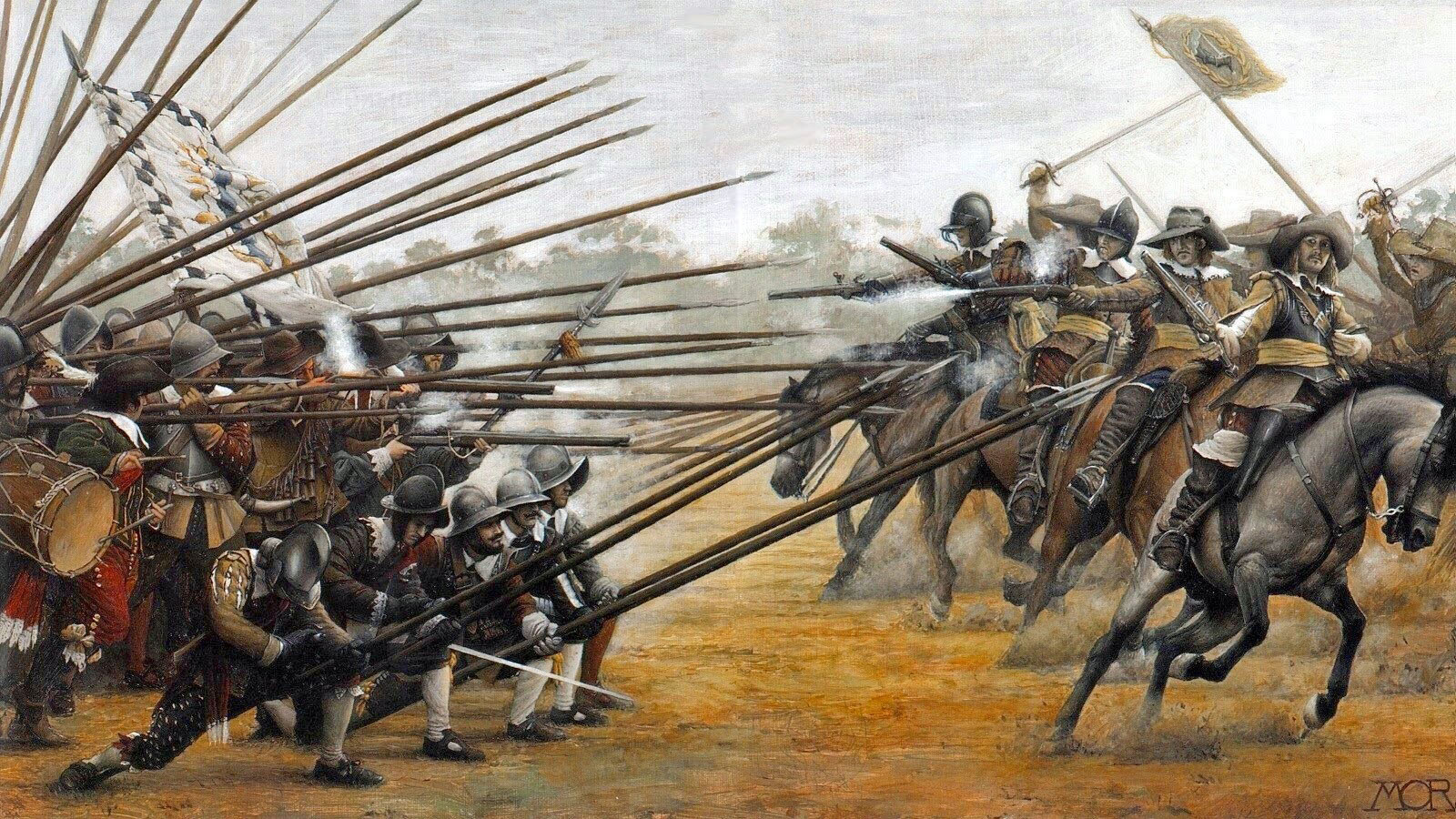

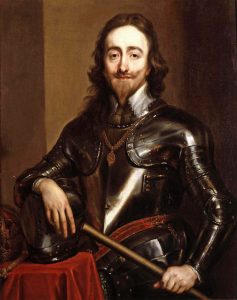

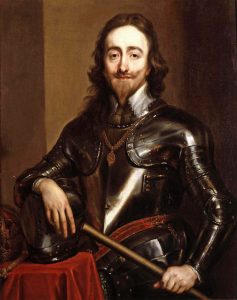

The English Civil War erupted in 1642, as a conflict of authority between the King and Parliament. King Charles I claimed to rule by divine right, deriving his sovereignty from religion. By contrast, Parliament professed to represent the will of the people. But only a small minority of males had the right to vote in parliamentary elections. Women had no vote.

Parliamentarians and Royalists warred throughout Britain until the defeat and execution of Charles I in 1649 and the installation of a republic under Oliver Cromwell.

Parliamentarians and Royalists warred throughout Britain until the defeat and execution of Charles I in 1649 and the installation of a republic under Oliver Cromwell.

The Civil War stimulated seminal debates concerning power and authority. There was a growth of dissident Protestant groups, who saw the established Protestant Church of England as too hierarchical and conservative.

These widening schisms forced the question of the legitimation of government authority onto the immediate agenda.

Political ideas of the Levellers

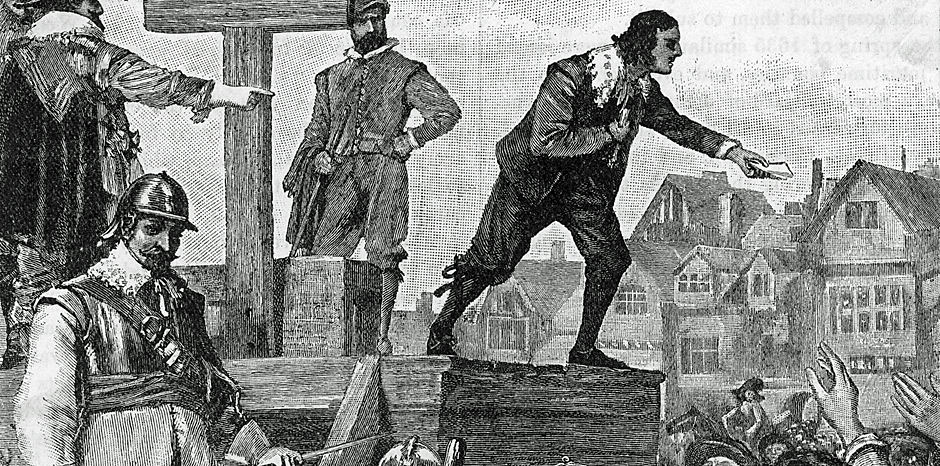

Prompted by debates over what to do with the monarchy and the King after his defeat, a major political movement developed within the Parliamentarian army. They were called Levellers.

Participants in the earlier anti-enclosure uprising in the Midlands in 1607 had been called “levellers” because they levelled hedges and fences.

Participants in the earlier anti-enclosure uprising in the Midlands in 1607 had been called “levellers” because they levelled hedges and fences.

The Levellers of the 1640s were given this nickname by their enemies, and they repeatedly repudiated the description. They often protested that they were not promoting the “levelling” of landed estates or any general redistribution of property.

The Levellers emphasized popular sovereignty, an extended male franchise, equality before the law, and religious tolerance. They believed in natural and inalienable rights, bestowed by God.

The inalienability of these rights put limits on the powers of any majority in Parliament, because democracy cannot stifle inalienable rights. But otherwise they were strong supporters of democracy.

While they defended private property, they railed against undemocratic tyranny. Hence their position was different from some modern libertarians who, while generally supporting liberty, argued on occasions that if private property rights were threatened, then democracy might justifiably be replaced by temporary dictatorship.

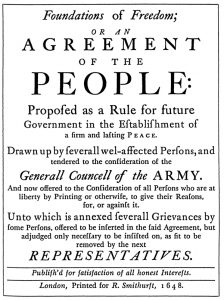

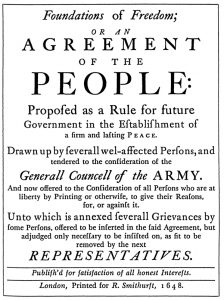

From 1647 to 1649 the Levellers published a series of manifestos entitled The Agreement of the People. The Levellers were the first political movement in Europe to call for the separation of church and state and for a secular republic.

Authority would be vested in the House of Commons rather than in the King or the House of Lords. Specified “native rights” were declared sacrosanct for all Englishmen: freedom of conscience, freedom of worship, freedom from impressment into the armed forces, and equality before the law.

Authority would be vested in the House of Commons rather than in the King or the House of Lords. Specified “native rights” were declared sacrosanct for all Englishmen: freedom of conscience, freedom of worship, freedom from impressment into the armed forces, and equality before the law.

The Levellers argued for a constitution based upon an extended manhood suffrage and biennial Parliaments. But they did not advocate female suffrage. And as C. B. Macpherson noted:

“the Levellers consistently excluded from their franchise proposals two substantial categories of men, namely, servants or wage-earners, and those in receipt of alms or beggars.”

Oliver Cromwell and the Levellers

The Levellers were influential in Cromwell’s army. At a rendezvous near Ware in Hertfordshire on 15 November 1647, two regiments carried copies of the Agreement of the People and stuck pieces of paper in their hat-bands with the Leveller slogan “England’s Freedom, Soldiers’ Rights”.

With swords drawn, Cromwell and some of his officers rode into their ranks and ordered them to take the papers from their hats. One of the soldiers was swiftly executed for mutiny.

Putney Debates 1647

Siding with the Levellers in the Putney Debates of 1647, the parliamentarian Colonel Thomas Rainsborough argued that both the rich and poor had a right to a decent life, and that “every man that is to live under a government ought first by his own consent to put himself under that government”.

Burford Churchyard Memorial

But in 1649, Rainsborough was killed, Leveller-led army mutinies in London and Oxfordshire were crushed, and Cromwell effectively destroyed the Levellers as a political force.

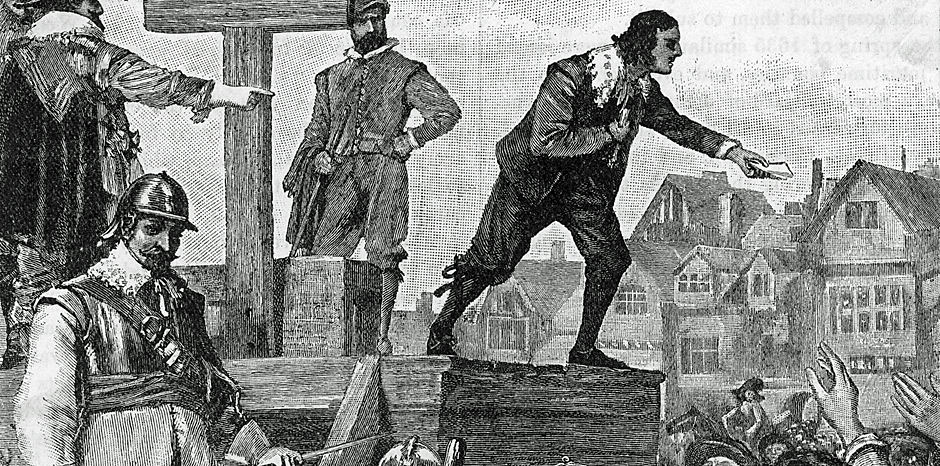

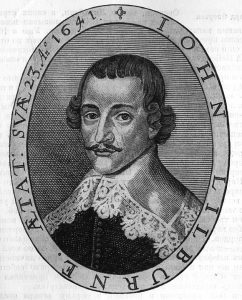

John Lilburne

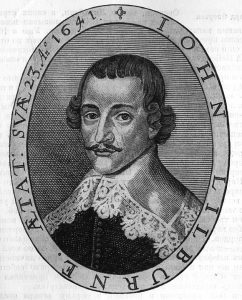

John Lilburne, the Leveller leader, came from County Durham. He was originally a Puritan and he later converted to Quakerism. Arrested in 1637 for circulating unlicensed pamphlets, he was fined £500, whipped, pilloried, and imprisoned.

John Lilburne

During the Civil War, Lilburne served as an officer in the Parliamentarian army. For his agitation against the Cromwellian authorities he spent several more years in prison.

Lilburne coined the term “freeborn rights”, defining them as rights with which every human being is born, as opposed to rights bestowed by government or by its laws. He advocated an extended male suffrage, equality under the law and religious tolerance.

Asked in a 2015 interview with the New Statesman to identify the historical figure he most admired, Corbyn named John Lilburne. In a talk in the same month, Corbyn wrongly hinted that Lilburne was a socialist. In fact, Lilburne was a liberal, although that political term was not in use at the time.

Lilburne explained in 1647 that the term “Leveller” applied to him and his party, only in the sense of equality under the law, namely their “desire that all alike may be levelled to, and bound by the Law”.

But much later their socialist admirers assumed that they wished to “level” all property as well. There is no basis for this supposition in Leveller writings.

The Levellers and common ownership

The Levellers declared that rights to liberty and property were innate to every person. Individuals had rights over their thoughts and bodies, without molestation or coercion, and everyone had the natural right to own private property. The Levellers did not promote common ownership, except when it resulted from the voluntary pooling of the property of everyone involved.

Generally the Leveller leaders did not campaign against the enclosure of common lands. Instead they upheld legally-acquired rights of property. The Marxist historian Christopher Hill pointed out that the Levellers “sharply differentiated themselves from the Diggers who advocated a communist programme”.

A defence of private property and a rebuttal of “levelling” appears in the final, May 1649 version of the Leveller Agreement of the People, in a passage addressed to Members of Parliament:

“We therefore agree and declare, That it shall not be in the power of any Representative … [to] level men’s Estates, destroy Propriety, or make all things Common.”

Even if representatives in the legislature were democratically elected, they did not have the right to overturn individual rights to property.

Lilburne’s arguments against common ownership

Likewise, Lilburne was repeatedly obliged to rebut the charge that the Levellers desired to “level” all property. He wrote in 1652:

“In my opinion and judgment, this Conceit of Levelling of property … is so ridiculous and foolish an opinion, as no man of brains, reason, or ingenuity, can be imagined such a sot as to maintain such a principle, because it would, if practised destroy not only any industry in the world, but raze the very foundation of generation, and of subsistence or being of one man by another.”

Lilburne then explained why this was so:

“For as industry and valour by which the societies of mankind are maintained and preserved, who will take the pains for that which when he hath gotten is not his own, but must be equally shared in, by every lazy, simple, dronish sot? Or who will fight for that, wherein he hath no interest, but such as must be subject to the will and pleasure of another, yea of every coward and base low-spirited fellow, that in his sitting still must share in common with a valiant man in all his brave noble achievement?”

Lilburne concluded:

“… those men in England, that are most branded with the name of Levellers, are of all in that Nation, most free from any design of Levelling, in the sense we have spoken of.”

As well as rebutting the charge of “levelling”, Lilburne here defended the institution of private property in terms of its incentives for “industry” and maintaining “subsistence”. If everything were “equally shared”, then the “lazy” would benefit as much as those “who will take the pains”, thus diminishing incentives for individual effort. Incentives to work hard would be lessened.

The 1/n problem

The 1/n problem

With the above words, Lilburne pointed to the crucial problem of scale in all communistic ventures.

It is a version of what economists call “the free-rider problem”. As the size of the community increases, the free-rider problem can be exacerbated. If the number of people in a working community that shares its income is n, then individual incentives to contribute to community output are very roughly in proportion to 1/n.

As n increases, the extra effort of any single individual is rewarded less, because the output from extra effort is shared between n people. We may call this the 1/n problem. As far as I am aware, Lilburne was the first person to identify it.

Crucially, at low values of n, such as in a family or in a small cooperative, incentives to work hard can be enhanced by face-to-face mechanisms involving reciprocity, trust, commendation, satisfaction, shame, scorn or punishment.

These social mechanisms are effective because they have evolved in human tribes over millions of years. Elinor Ostrom’s case studies of the community management of common pool resources show what is feasible in more recent settings.

Elinor Ostrom

Hence some form of socialism may work on a small scale. But at higher levels of n these interpersonal mechanisms become relatively less effective. Other incentives, involving money and property, are required.

The Levellers on free trade and (state) monopolies

The Levellers advocated free trade. For them, the basic division in society was not between workers and owners of property: it was between the rich and influential – who profited from (state and other) monopolies and government favours – and the rest of the people. A clause in the May 1649 version of The Agreement of the People tells Parliament:

“That it shall not be in their power to continue or make any Laws to abridge or hinder any person or persons, from trading or merchandizing into any place beyond the Seas, where any of this Nation are free to trade.”

Leveller leaders Lilburne, Richard Overton and William Walwyn attributed the existence of low wages to monopolies, restrictions on trade, and excise taxes.

In 1652 Walwyn presented to the Parliamentary Committee for Trade and Foreign Affairs a defence of free trade against the Levant Company, urging the abolition of monopolies and trade restrictions. Walwyn saw free trade as a common right, conducive to common good.

The Levellers and Diggers contrasted

Yet the myth that the Levellers promoted common ownership persists. Tony Benn often mentioned the Levellers favourably, but he ignored their strong commitment to private ownership, and instead suggested that their arguments pointed to “common ownership and a classless society”.

An entertaining four-part television series set during the English Civil War entitled The Devil’s Whore (released in North America as The Devil’s Mistress) has Rainsborough speaking in favour of common ownership, without any objection from Lilburne.

An entertaining four-part television series set during the English Civil War entitled The Devil’s Whore (released in North America as The Devil’s Mistress) has Rainsborough speaking in favour of common ownership, without any objection from Lilburne.

There is no historical evidence to sustain such depictions. They are fantasies promoted by Benn, Brockway, Corbyn and others.

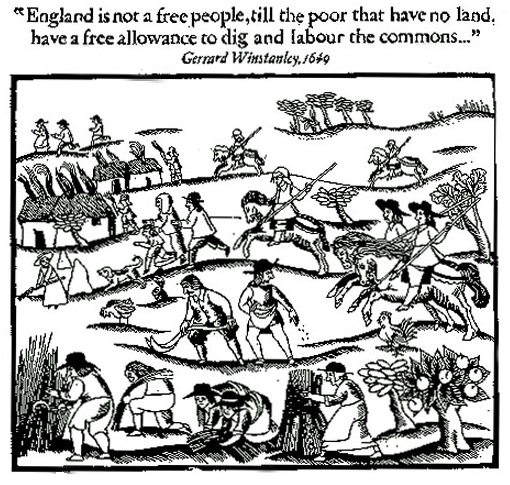

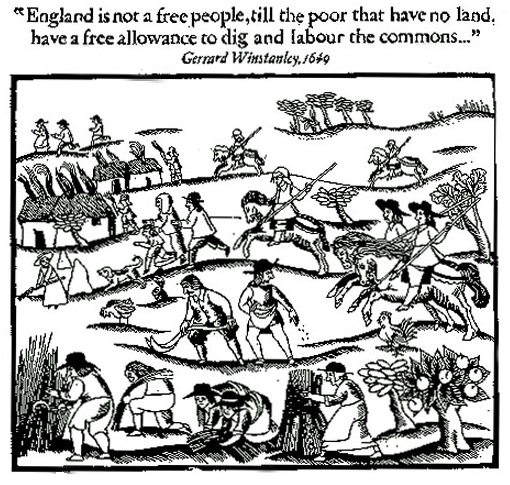

By contrast, the Diggers opposed private property. From 1649-1650 groups of Diggers squatted on several stretches of common land in southern England. They set up communes whose members worked together on the soil and shared its produce. The Digger leader Gerrard Winstanley published a series of pamphlets advocating common ownership of land.

The Diggers

Winstanley regarded the institution of property as a limitation of the freedom of others. Land was bestowed to all by God. Unlike the Levellers, Winstanley criticized trade, because it led to cheating and discontent. He envisioned an agrarian society, in which all goods would be communally owned, and all commerce and wage labour would be outlawed.

Hence the Levellers and Diggers had very different ideological positions. The Levellers advocated individual autonomy, private ownership and free trade. Although they appealed to religion, they saw democratic legitimation as the source of government authority. By contrast, the Diggers proposed a rigid, small-scale, religiously-inspired, agrarian communism.

Conclusion

The Levellers were political theorists as well as activists. They helped to develop the intellectual foundations of Enlightenment liberalism.

Unlike later liberals such as Thomas Paine, they did not advocate a welfare state. Unlike John Stuart Mill they did not call for female suffrage. Unlike twentieth century liberals such as John A. Hobson, John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge they did not advocate substantial state regulation in a mixed capitalist economy.

But the Levellers were liberals and democrats nevertheless. Their arguments against large-scale socialism remain pertinent today.

11 October 2017

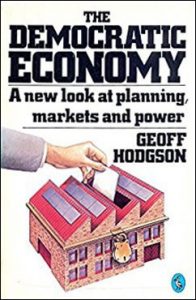

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Benn, Tony (1976) ‘What would the Levellers do Today?’ 15 May. https://seagreensociety.wordpress.com/tag/levellers-day/.

Brailsford, H. N. (1961) The Levellers and the English Revolution (London: Cresset Press).

Brockway, Fenner (1980) Britain’s First Socialists: The Levellers, Agitators and Diggers of the English Revolution (London: Quartet).

Hampton, Christopher (ed.) (1984) A Radical Reader: The Struggle for Change in England, 1381-1914 (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Hill, Christopher (1975) The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas During the English Revolution (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Macpherson, Crawford B. (1962) The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism: Hobbes to Locke (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Manning, Brian (1976) The English People and the English Revolution, 1640-1649 (London: Heinemann).

Morton, A. L. (1975) Freedom in Arms: A Selection of Leveller Writings (London: Lawrence and Wishart).

Ostrom, Elinor (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Otteson, James R. (ed.) (2003) The Levellers: Overton, Walwyn and Lilburne – Works by these and by other British Levellers (Bristol: Thoemme Press).

Robertson, D. B. (1951) The Religious Foundations of Leveller Democracy (New York: Kings Crown Press, Columbia University).

Woodhouse, A. S. P. (ed.) (1951) Puritanism and Liberty: Being the Army Debates of 1647-9 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Left politics, Liberalism, Socialism, Tony Benn

October 1st, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

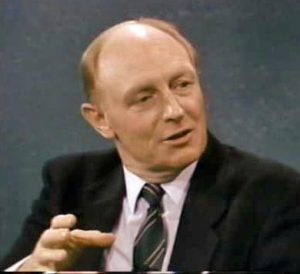

Ken Loach was a prominent celebrity at the 2017 Labour Party conference, being photographed in the main conference hall and elsewhere in close proximity to Jeremy Corbyn. But it seems that Loach was not then a member of the Labour Party. Instead he was a recent founder of a rival political party – Left Unity – which was set up to oppose Labour.

This is not a personal attack on Loach. Generally, he is a dignified and caring person. He is entitled to his views, but they are dogmatic and impractical. The question is why Labour now welcomes with open arms a member of a rival political party, with views far more extreme than those that Labour has traditionally professed.

What does Loach’s invitation tell us about the state of the Labour Party today? We need to look at his political views. We need to understand the politics of a celebrity that Labour now chooses to put on public display.

What does Loach’s invitation tell us about the state of the Labour Party today? We need to look at his political views. We need to understand the politics of a celebrity that Labour now chooses to put on public display.

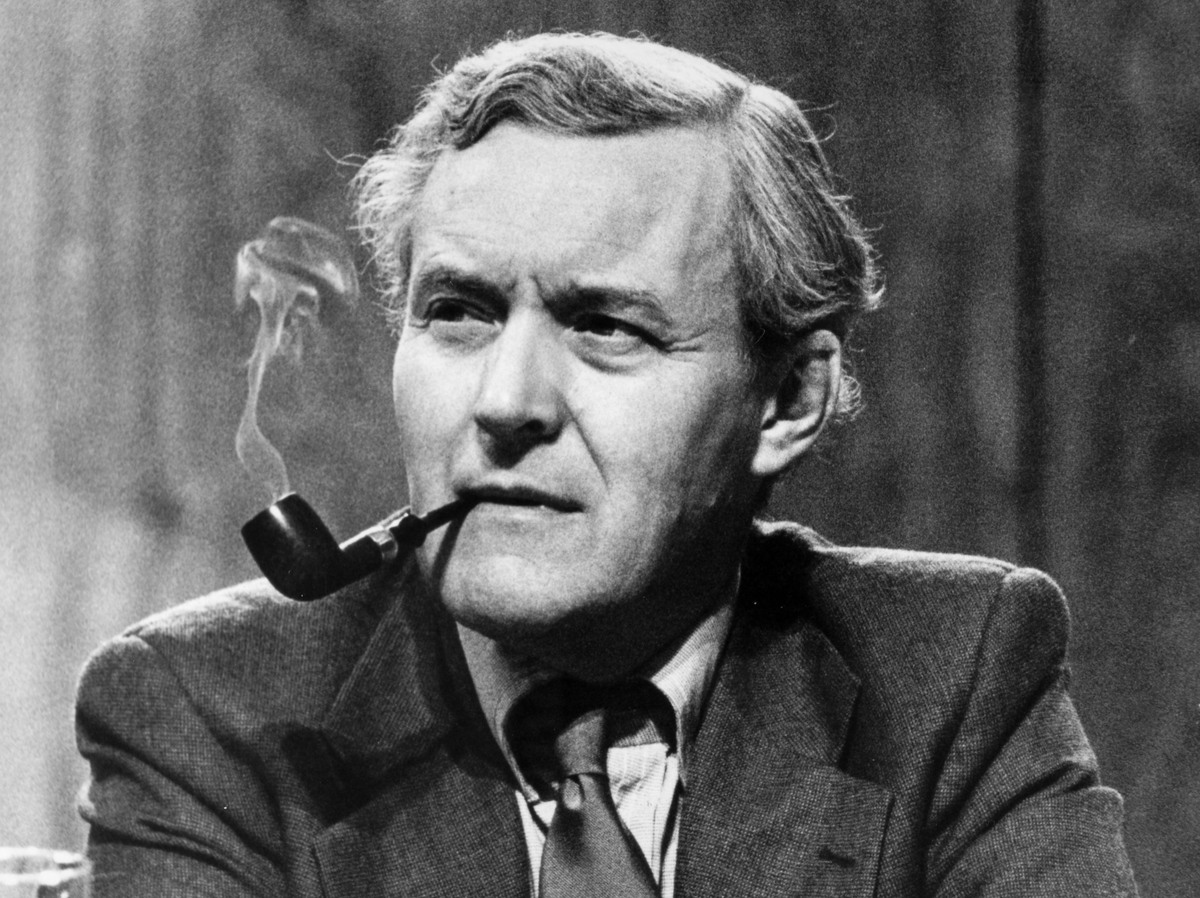

Ken Loach’s contributions to film and to public debate

Loach is a brilliant film director and his work has rightly received global recognition. Two of his films received the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. He has also received BAFTA awards.

His best work shows us in moving, dramatic detail how working class people can be trapped by the system, suffering poverty and the tragic loss of their human potential. Such were the personal and emotional stories in Cathy Come Home (1966), Poor Cow (1967), Kes (1969), Raining Stones (1993) I, Daniel Blake (2016) and other great films. Loach, with his gritty, realist style has awakened and re-awakened us over decades to the shamefully enduring problems of poverty, inequality, discrimination and exploitation.

Other projects by Loach are different in style. He was to direct Jim Allen’s controversial stage play, Perdition. Allen was a Trotskyist and a close friend of Loach, until his death in 1999. Presented as a courtroom drama, the play dealt with an allegation of collaboration between Hungarian Zionists and the Nazis during the Holocaust. This allegation has been strongly contested by historians.

Other projects by Loach are different in style. He was to direct Jim Allen’s controversial stage play, Perdition. Allen was a Trotskyist and a close friend of Loach, until his death in 1999. Presented as a courtroom drama, the play dealt with an allegation of collaboration between Hungarian Zionists and the Nazis during the Holocaust. This allegation has been strongly contested by historians.

The play was due to open at the Royal Court Theatre in January 1987, but it was cancelled 36 hours before the opening night. This same claim of Zionist-Nazi collaboration, citing the same contested sources, was repeated more recently by Ken Livingstone and it led to his suspension from the Labour Party.

From gritty realism to unrealistic politics

In contrast to the gritty realism of his working class dramas, Loach takes a less realistic line when it comes to history.

For example, Land and Freedom (1995) is set in the Spanish Civil War. The script was written by Allen. Scenes in Land and Freedom depict an ideological battle within the Republican camp. The Communist Party opposes others on the left, including anarchists and revolutionary socialists.

Against the Communist Party, Allen and Loach took the side of the revolutionary socialists calling for a socialist revolution and for the seizure of the land by the peasants. This unrealistic ultra-leftism mars the film. It brushes aside the argument that General Franco’s insurrectionary fascism would have been best fought by the broadest possible popular front, from liberals to communists.

A similar unrealism appears in The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006). The script was written by Paul Laverty. The film is set in Ireland in the period 1919-1923. It depicts the struggle for independence and the subsequent civil war.

A similar unrealism appears in The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006). The script was written by Paul Laverty. The film is set in Ireland in the period 1919-1923. It depicts the struggle for independence and the subsequent civil war.

Again there is a sequence where key characters discuss their strategic options. Again full-blooded socialism is mooted as the only way of liberating the country, from poverty and from British tyranny.

But a socialist revolution in Ireland in 1919-23 was even less likely than one in the 1930s in Spain. Ireland was a country of small tenant farmers. It had little urban concentration or industrial development. The small urban working class was not as well organised as in Britain. Socialism had a tiny following.

A socialist revolution in these circumstances was a fantasy of the film’s director and its script writer. Again the insertion of unrealistic revolutionary socialist preaching spoils the film.

Left Unity

Left Unity founded in 2013 when film director Loach appealed for a new party to replace the Labour Party. In March 2014 Loach condemned Labour for following other parties by upholding “the importance of the market economy”. Like other governments, Labour “cuts back on public enterprise and prioritises the interests of big corporations and private companies”. Loach continued:

Loach called on true socialists to abandon Labour and join Left Unity. More than 10,000 people supported Loach’s appeal. In 2014, the party had 2,000 members and 70 branches across Britain.

Left Unity put up ten candidates in the 2015 general election, to stand against prominent Labour figures including Andy Burnham and Harriet Harman. Left Unity also contested some local elections. There is an unintentional irony in the u-word in its name.

Left Unity put up ten candidates in the 2015 general election, to stand against prominent Labour figures including Andy Burnham and Harriet Harman. Left Unity also contested some local elections. There is an unintentional irony in the u-word in its name.

Rejecting social democracy

At the launch of his party’s manifesto, Loach said that Left Unity is “against the logic of the market” which he believed had “failed in every respect”.

Loach decisively rejected social democracy. Referring to Labour and other similar parties, he said that “they’re mainly social democrat parties that think you can manipulate the markets to the advantage of ordinary people”.

Loach decisively rejected social democracy. Referring to Labour and other similar parties, he said that “they’re mainly social democrat parties that think you can manipulate the markets to the advantage of ordinary people”.

For Loach, such manipulation is impossible: “The market demands cheap labour, it demands labour that can be turned on and off like a tap, zero-hours contracts, short-term contracts, agency work.” For him, the market offers us no other option. Hence social-democratic reformism and Keynesian intervention are both fatally flawed.

Nationalising the supermarkets

The 2014 Constitution of Left Unity supported a mixed economy, as a transitional arrangement within an over-arching national plan. But in its 2015 General Election Manifesto, Left Unity took a much more extreme line, reflecting Loach’s absolutist anti-market views:

Note here the common ownership of all “means of producing wealth”. There are no exceptions. Everything, from banks to supermarkets, would be publicly owned. Marx would have liked that.

Lenin would have also liked the suggestion that this fully planned economy should be run democratically. Lenin argued this in his State and Revolution in 1917. But as soon as his Bolsheviks came to power they had to abandon the idea. Such ultra-democracy is totally impractical.

A quick leap to the higher phase of communism

But Marx might have criticised the Labour Unity Manifesto’s conflation of long and short-term aims. In his Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx wrote that “from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” could apply only in

By contrast, Loach and Left and Unity put “to each according to their needs” alongside immediate aims in an election manifesto. It seems that they wanted to leap to “a higher phase of communism” right away.

Loach and Left Unity now want to abolish all markets and all private ownership of the means of production. This went much further than Corbyn and his team, who have argued for a “mixed economy”. But Corbyn’s embrace of Loach and his views might suggest that they share the long-term view that all markets and private enterprise should be abolished.

Even in Marxist terms, the position of Loach and Left Unity on markets is rather crude. Markets have existed for thousands of years. Marx never saw them as the key defining feature of capitalism – instead, for him, it was the system of wage labour. Following Joseph Schumpeter, I would also stress the role of finance.

Resemblances with pro-market economics

But remarkably, the views of Loach and Left Unity replicate some arguments by extreme pro-market economists. Against a majority view, economists such as Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek argued that a mixed economy cannot work. As von Mises put it in 1949:

Left Unity seems to follow the same logic as these uncompromising, pro-market economists. By contrast, many economists accept that there is a case for some judicious state regulation and intervention in a market economy, to deal with problems such as externalities and market instability.

In my book Conceptualizing Capitalism I go further, to argue that the state is necessary to part-constitute the legal framework of a capitalist economy. Hence some state intervention in a market economy is unavoidable. Given this, the practical question for progressives is where and how it should intervene. The literature on varieties of capitalism shows that many different outcomes are possible within capitalism, and defects such as inequality can be significantly diminished.

In my book Conceptualizing Capitalism I go further, to argue that the state is necessary to part-constitute the legal framework of a capitalist economy. Hence some state intervention in a market economy is unavoidable. Given this, the practical question for progressives is where and how it should intervene. The literature on varieties of capitalism shows that many different outcomes are possible within capitalism, and defects such as inequality can be significantly diminished.

In particular, Loach and Left Unity overlook the successes of social democracy, particularly in Northern Europe. During the twentieth century they have built up strong welfare states, redistributed some wealth and regulated markets.

Of course, there have been strong and sustained attempts to reverse these achievements. But it is much more realistic to defend social-democratic gains against the free-marketeers than to urge a quick leap to the higher phase of communism.

Against NATO – for a boycott of Israel

The foreign policy of Left Unity is “anti-imperialist”. Like Corbyn, it calls for Britain to quit NATO. But unlike Corbyn, Left Unity does not support Brexit.

Loach supports the boycott of Israel, calling it an “apartheid regime”. Before his election as leader, Corbyn also pushed for boycotts of Israel. This selective targeting of Israel now seems a widespread opinion among Labour members, but it is not official party policy.

Rather than accepting that anti-Semitism as a problem within Labour, Loach argues that the claims are false: those that raise the issue are trying to undermine Corbyn’s leadership.

Supporting ISIS

Another remarkable incident tells us not so much about Loach, but about some of the people who join Left Unity.

In a 2014 conference of Left Unity, a minority proposed support for the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). True to their Leninist credentials, they argued that the left “has to acknowledge and accept the widespread call for a Caliphate among Muslims as valid and an authentic expression of their emancipatory, anti-imperialist aspirations.” They supported ISIS as a “stabilising force” with “progressive potential”.

A warm welcome

In the 2015 General Election, Left Unity’s parliamentary candidates received a pitiful average of 288 votes – all losing their deposits. Later that year, after Corbyn’s election as Labour leader, Left Unity voted against affiliation to the Labour Party but resolved not to put up any more candidates against Labour.

Because of Corbyn’s leadership victory, several hundred members resigned from Left Unity and joined Labour. Left Unity is now a depleted party, without a viable independent strategy.

It seems that Labour is now welcoming their members, ignoring their extremist and unrealistic views and their fervent opposition to social-democratic reform. This is a suspicious unity of a dubious left.

1 October 2017

Minor edits – 3, 5 Oct 2017

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Cohen, Nick (2007) What’s Left? How the Left Lost its Way (London and New York: Harper).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Mises, Ludwig von (1949) Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (London and New Haven: William Hodge and Yale University Press).

Rich, Dave (2016) The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism (London: Biteback).

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Labour Party, Left politics, Markets, Nationalization, Private enterprise, Socialism, Tony Benn

September 20th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

I was born in 1946. I lived in a council house until I was 16. My family were Labour. My privilege was not money, but that my parents and grandparents all valued education and culture. But none of them obtained a university degree, because they were less accessible at the time.

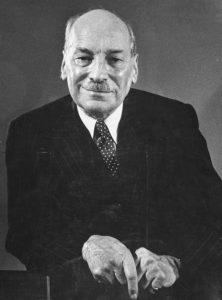

Harold Wilson

I became involved in the Labour Party in 1964 and then saw myself as a Tribune socialist following the steps of great radicals such as Michael Foot. After welcoming Harold Wilson’s election victory in 1964, I became critical of the new Prime Minister because of his nominal support for the US in the Vietnam War.

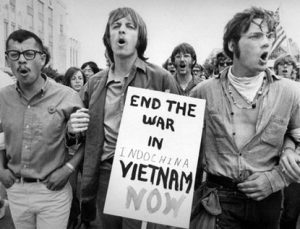

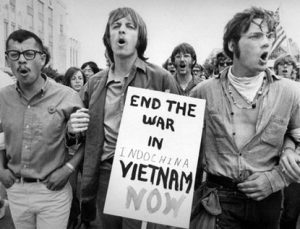

Vietnam and Marxism

For my baby-boom generation, the Vietnam War was a great generator of radicalism. Like many of my university friends, I became a Marxist in 1966. We were drawn into a turbulent and exciting world that combined activism with ideas and debate. I saw myself as a Marxist until about 1980.

I studied mathematics and philosophy from 1965 to 1968 and economics from 1972 to 1974. Both periods were at the University of Manchester. In the intervening years I taught myself Marxist economics. My knowledge of economics became enduringly significant in my political evolution.

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

Marxists dominated the activists on the university campuses. The left was divided and fractious. There were Soviet Bloc loyalists in the Communist Party of Great Britain. There were lovers of Mao Zedong and several rival Trotskyist sects. I could not bring myself to support any totalitarian regime – East or West – so I joined the forerunner of what is now the Socialist Workers’ Party, which saw everything existing as “capitalist”.

My departure from the SWP came in 1971 when they expelled a dissident faction with which I sympathised. (That critical faction eventually became the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty, of Momentum fame in the Corbyn Era.)

I flirted briefly with the International Marxist Group, which included glamorous figures such as Tariq Ali, and Robin Blackburn of the New Left Review. The IMG was stronger in its support for the women’s movement and for gay rights.

After a few years among the sects I could see that something was wrong. These groups were aiming to help create a much better society, but they were generally dogmatic and intolerant. Some were ruthless, pugnacious and fanatical. I did not want to see any social system facilitated or run by these people.

But on the other hand I then accepted the Marxist view that capitalism was exploitative and frequently led to oppression and war. The evidence of this was seemingly before our eyes.

Re-joining Labour and changing strategy

After Labour’s electoral defeat in 1970, there was a strong and growing left in the Labour Party and that seemed the best hope for socialists. Against the advice of Ralph Miliband (whom I knew personally) and others, I re-joined Labour in 1974.

In 1975 I published a pamphlet entitled Trotsky and Fatalistic Marxism. This tried to explain the fanaticism and intolerance of many Marxists in terms of their belief in the imminent decay and collapse of capitalist democracies. Trotskyists had failed to appreciate the enormous expansion and dynamism of capitalism after 1945. Their explanations of the survival of capitalism were weak.

Published in 1977, a longer work entitled Socialism and Parliamentary Democracy elaborated more of my thinking. Marxist-Leninists believed that parliament and the capitalist state should be “smashed”. Influenced by Max Weber and others, I argued that in modern democracies, government drew their perceived legitimacy from parliamentary elections. If socialism became a majority view, then socialists could and should gain a majority in parliament.

In the book I criticised the 1968 revolutionary movement in France for boycotting the elections called by President Charles de Gaulle in that year. Victory in the elections gave de Gaulle legitimacy. The huge movement of students and workers was crushed.

Paris – May 1968

As I had anticipated, my heresies were dismissed out of hand by the far left sects. But the book proved to be rather influential in the UK and internationally. It received a strongly sympathetic hearing on the Labour left. It was translated into Italian, Japanese, Spanish and Turkish. It persuaded a leading member of the violent Basque separatist group ETA to abandon terrorism.

I don’t know if he read my book, but Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the leader of the revolutionary movement in France in May 1968, later argued that it had been a mistake to boycott the French parliamentary elections.

Labour had been reconciled to the parliamentary road to socialism since its formation. The sects argued that it wouldn’t work. My response was that insurrection would not work either. In democracies we needed a combination of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary action.

Questioning ends as well as means

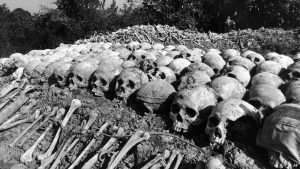

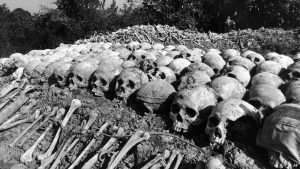

The killing fields in Cambodia affected me deeply. After seizing power in 1975 the Khmer Rouge forced everyone into the countryside and obliterated about two million people – a quarter of the Cambodian population – in the pursuit of their communist utopia.

I could not dismiss this as an aberration. After all, the Khmer Rouge aims, which included the abolition of money, private property and markets, were central to the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.

Khmer Rouge Killing Fields

The far left were able to publish papers and debate ideas because they lived in a democracy that tolerated freedom of expression. But the ideas and actions of the sects, if they gained influence or power, would curtail these very liberties upon which they had depended.

Crucially, I was not naïve enough to believe that freedom and political pluralism could be guaranteed simply by the goodwill of a more enlightened Marxist leadership, who valued these things more than the Khmer Rouge. Good intentions were not enough.

I had retained a good lesson from Marxism. Effective ideas and practices draw their strength from agglomerations of power sustained by the structures of the politico-economic system. Hence a genuinely pluralist and tolerant political sphere depended on pluralism and decentralisation in the economic domain. A pluralist polity requires a pluralist economy.

Beatrice & Sidney Webb

Prominent Labour thinkers such as Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and G. D. H. Cole had all argued for a decentralised socialist system. But they still sought the abolition of private property and markets. The state would ultimately own everything. So what institutional, legal or other politico-economic forces could stop it retrieving all delegated powers to the centre, when deemed required, or when goodwill wore thin?

Any viable socialism always needs markets

I came to the view that genuine and lasting decentralisation would depend on the existence of organisations with some genuine autonomy and legal independence, providing powers to own property and trade with other organisations. Any viable socialism would always need markets – it was not simply a matter of tolerating or compromising with them.

This crucial transition of my thinking occurred between 1977 and 1980. I cannot recall the detailed influences. But I am sure that the initial impetus did not come from Ludwig von Mises or Friedrich Hayek. I did not delve deeply into their works until the early 1980s.

János Kornai

There had been several socialist proposals to nationalise the sector producing capital goods but retain competition and markets for consumer goods. I was more attracted by the Hungarian economist János Kornai’s more sophisticated proposal (originally published in 1965) to use a dynamic combination of markets and planning, where planning provided strategic impetus, and markets signalled information and gave scope for innovation and planning adjustment.

Over the new year of 1979-1980 I went on a short tourist group visit to the Soviet Union. Some of my companions were dewy-eyed admirers of the system, but I was prepared for its flaws, including the ubiquitous black markets and corruption.

I had been given the address in Moscow of an Englishman married to a Russian. As a former Communist, he explained in detail in his apartment how and why his views had quickly changed: “I challenge any supporter of the Soviet Union to live here just for six months.”

Alec Nove

When Alec Nove published a classic article on feasible socialism in New Left Review in early 1980 I was ready for it. Nove also argued that markets were essential to any viable socialism. He realised that he was attacking deeply-ingrained orthodoxy on the left.

(Later I had the pleasure of meeting both Kornai and Nove several times. Nove died in 1994 but Kornai is still alive. I am delighted to be invited as a keynote speaker at a conference in his honour in Budapest in 2018.)

Labouring as a revisionist

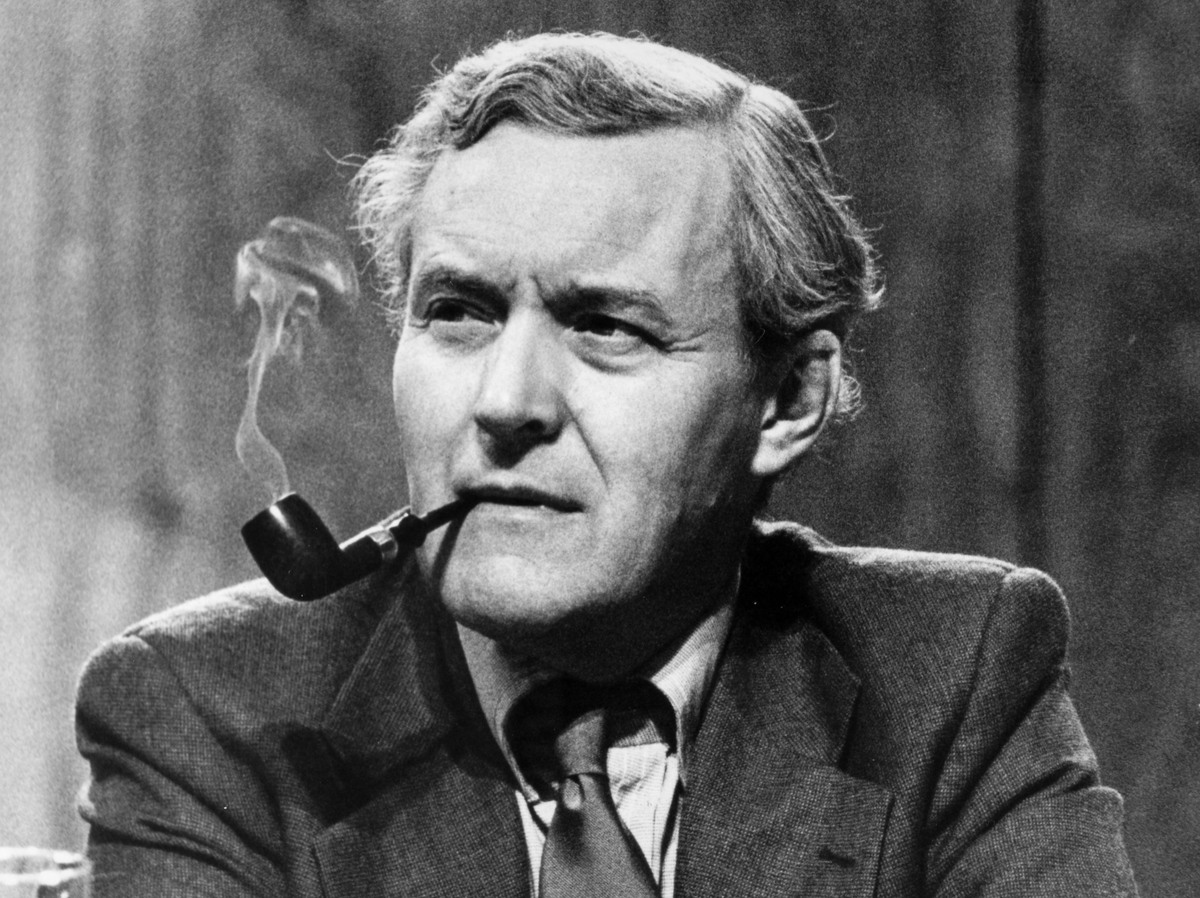

Any acceptance of markets was an anathema to followers of both Karl Marx and Tony Benn. Benn distanced himself from those who supported the persistence of markets.

But I found common ground with Benn and others over what was called “the alternative economic strategy”. I outlined my positive views on this in a pamphlet entitled Socialist Economic Strategy in 1979. It was published by Independent Labour Publications.

Independent Labour Publications was the residue of the old Independent Labour Party, which had played a central role in Labour history from the 1890s to the 1940s. The Independent Labour Party split from the Labour Party in 1931. But in 1975 it formally dissolved as a party and rejoined Labour as Independent Labour Publications.

I was involved in this organisation briefly. Despite outward appearances they turned out to be another sect, lacking any vision of a workable socialism. They too were uneasy about my revisionism. Although my Socialist Economic Strategy was a bestseller by their standards, they refused to reprint it. We parted company in 1981.

Geoff Hodgson, Jean Shepherd & John Maguire in 1979

In 1979 I was the unsuccessful Labour Parliamentary Candidate for Manchester Withington. The seat became Labour in 1987.

I met Benn a few times and supported him in the 1981 deputy leadership election. This alignment was marked in my book Labour at the Crossroads, published in that year. Therein I again supported the alternative economic strategy. But against Benn himself, I argued in that book that in some sectors of the economy “there is no substitute for competition and a market” (p. 206).

(In his important book on The Labour Party’s Political Thought, Geoffrey Foote quotes me (pp. 320, 347) as a “Bennite”. But because of my explicit acceptance of markets, I was unrepresentative of the Bennite stream of thought.)

Subsequently my opinion of Benn shifted. He was a magnificent speaker, but his writings on socialism are vague and unclear. His use of history is unscholarly and cavalier. He was not a well-read intellectual like Michael Foot.

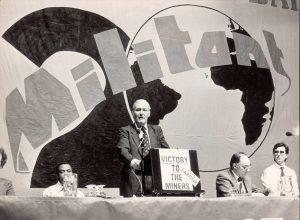

Tony Benn at a Militant meeting

While Benn’s “alternative economic strategy” accepted markets and a private sector for the present, it seemed to me that he wanted to move eventually toward a socialist economy without any markets at all. It was no accident that Benn and his followers defended the Trotskyist sect Militant when they were pushed out of the party from 1985 to 1992.

In 1984 I published my book on The Democratic Economy, where I set out my view on the importance and complementarity of both markets and planning. My argument was framed in socialist language but therein I distanced myself from Marxism. The book received a critical response from many on both the soft and hard left.

The Labour Coordinating Committee

Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. One of Thatcher’s most popular policies was to promote the sale of council-owned housing to the tenants. Labour had opposed this policy. The disastrous 1983 defeat of Labour on a Bennite manifesto prompted a rethink, on this and several other issues.

For some of us, this rethink amounted to more than expedient doctrinal trimming. Encouraging home ownership was really a good idea: why should all property be owned by the rich? But while supporting home ownership, we argued that the government should also build more social housing and enlarge the stock available for rent by low-income families.

But these ideas met stiff resistance in the Labour Party ranks, and not simply from Trotskyist entryists such as Militant. The resistance from Benn and his supporters was substantial and even more enduring. It was clear that old-fashioned socialist ideas still had a tenacious appeal among Labour’s membership.

The Labour Coordinating Committee (LCC) became one of the primary modernising forces within Labour. Its leadership included Hilary Benn, Cherie Blair, Mike Gapes, Peter Hain, Harriet Harman, Kate Hoey (the Brexiteer) and others of enduring fame. I was elected to the LCC executive committee. We worked closely with the new leader Neil Kinnock, and with members of his shadow cabinet, including Robin Cook.

Changing Clause Four

I have detailed elsewhere my LCC attempt to bring about discussion to change Labour’s Clause Four. The version that had been in place since 1918 called for the “common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange”. This provided for no exception: all production would be in common ownership and there would be no private sector.

Although some Labour Party thinkers began to entertain the possibility of some private enterprise, many party members remained resolutely in support of widespread common ownership.

Against my efforts, the 1983 AGM of the Labour Coordinating Committee defeated the proposal that Clause Four should be rewritten. This was out of fear of antagonising the Benn wing. Instead, the LCC resolved that Clause Four should be “clarified”.

But a resolution on long-term aims, which I had helped to draft, was passed by a large majority. The resolution called for the Labour Party to draft a new statement of aims, upholding “that socialism involves extended democracy and real equality. Democracy under socialism is extended to industry and the community … and must involve a substantial decentralisation of power.”

There was a commitment to “political pluralism” and to “economic pluralism” involving “a variety of forms of common ownership … and the toleration of a small private sector including self-employed workers and other private firms.” The economy must be dominated by mechanisms of “democratic planning … but also accommodating a market mechanism in some areas.”

But there was strong hostility to these mildly revisionist ideas from within Labour’s ranks at the time, including from Jeremy Corbyn and Tony Benn.

Tony Benn & Jeremy Corbyn

The Guardian newspaper reported the LCC conference with the headline: “Labour breaks taboo on ownership”. For a while, the LCC tried to keep the conversation going on the need to revise Labour’s aims. The LCC held a conference in Liverpool in June 1984 on “The Socialist Vision”. But enthusiasm for this discussion fizzled out. By 1985 the LCC’s revisionist initiative had been kicked into the long grass. My efforts had failed.

But to their credit, Neil Kinnock and his deputy Roy Hattersley saw the need for Labour to modernise its aims. I advised them both for a while. But after 1987 I became less active in the Labour Party. My inactivity was born partly out of frustration that it was so difficult to shift Labour from its congenital hostility to markets and private enterprise.

But after a fourth election defeat in 1992 the party became more pliable. Tony Blair was elected as leader in 1994. Blair successfully changed the wording of Clause Four to endorse a strong private sector, but the dramatic rise of Corbyn in the party since 2015 shows that the old collectivist DNA has endured.

Towards liberalism

In many ways I have always been a liberal, especially in my support for freedom of expression, other human rights and democracy. By the late 1970s I also accepted the importance of markets and private property. But the emphasis in my thinking has shifted further in the last 30 years.

My academic works show a few markers of my political evolution. On page xvi of my 1999 book Economics and Utopia I wrote of my common ground with the US liberal John Dewey and with

“British social liberalism, which stretches from John Stuart Mill through Thomas H. Green to John A. Hobson, John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge.”

These thinkers still inspire me. But I would now also stress the importance of Thomas Paine. Other heroes include George Orwell and Arthur Koestler.

So by 1999 I was a true liberal, of social-democratic stripe. I had already moved some distance from the ideas in my 1984 book, which had over-stressed the possibilities for large-scale planning and for extensive democratic decision-making in large, complex economies.

But I still believe in judicious state intervention and regulation, and I am still an enthusiast for experiments with worker cooperatives and other forms of worker and community participation. With their lower levels of economic inequality, I see the Nordic countries as good role models for in the rest of the capitalist world.

From leaving Labour to joining the Liberal Democrats

In 2001 I left the Labour Party because of Blair’s energetic support for faith schools, Labour’s inadequate proposal for House of Lords reform and its neglect of the problem of economic inequality. I would have left over the Iraq War. Previously I had sometimes voted tactically for the Liberal Party, when they were second behind the Tories in my constituency. But what was tactical was also in growing part a matter of conviction.

I voted Liberal Democrat in the 1997, 2001, 2005 and 2010 general elections. But I did not approve of the coalition with the Tories. So the Liberal Democrats did not get my vote in 2015.

I re-entered political activity in 2016 after the Brexit referendum. My wife (Vinny Logan) had been a critical but close companion on my long journey since 1980. But unlike me she had always voted Labour. After the Brexit vote she joined the Liberal Democrats and I followed her after a few days. It will be a long hard slog to change British politics for the better, but it is vital that we try.

My wife and I were each brought up in a social culture where the Tories and the Establishment were the enemy, and the Liberals were seen as wishy-washy waverers in the class war. Labour was the only game in town.

It takes a long time to remove these ingrained preconceptions and learn that liberalism is the greatest legacy of the Enlightenment. It is the strongest guardian of both prosperity and freedom. Although Liberals have been in a minority, they are largely responsible for the foundation of the British welfare state. The NHS was originally a Liberal proposal. The Liberal Democrats constitute the most pro-EU party in the UK.

But some Liberal Democrats do not understand that it is the job of government in a recession to increase effective demand, particularly by increasing investment and raising disposable incomes for the poor. But the party is a broad church, and I will argue my corner in favour of Keynesian liberal economic policies.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

Today, both the Conservatives (now ruled by deceitful nationalists) and Labour (where the rising hard left dominate the timid moderates) are dangerous threats to the liberal and democratic rights and values that in the past we have taken too much for granted. We must now stand up to defend those rights and values, against dogma, ignorance, intolerance, petty nationalism and deceit.

20 September 2017

Minor edits – 25 September 2017, 22 October 2017, 10 April 2018.

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Foote, Geoffrey (1997) The Labour Party’s Political Thought: A History, 3rd edn. (London: Palgrave).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1975) Trotsky and Fatalistic Marxism (Nottingham: Spokesman).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1977) Socialism and Parliamentary Democracy (Nottingham: Spokesman).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1979) Socialist Economic Strategy (Leeds: Independent Labour Publications).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1981) Labour at the Crossroads: The Political and Economic Challenge to Labour Party in the 1980s (Oxford: Martin Robertson).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1984) The Democratic Economy: A New Look at Planning, Markets and Power (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1999) Economics and Utopia: Why the Learning Economy is not the End of History (London and New York: Routledge).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Kornai, János (1965) ‘Mathematical Programming as a Tool of Socialist Economic Planning’, reprinted in Nove, Alec and Nuti, D. M. (eds) (1972) Socialist Economics (Harmondsworth: Penguin), pp. 475-488.

Nove, Alec (1980) ‘The Soviet Economy: Problems and Prospects’, New Left Review, no. 119, January-February, pp. 3-19.

Nove, Alec (1983) The Economics of Feasible Socialism (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Nove, Alec and Nuti, D. M. (eds) (1972) Socialist Economics (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Posted in Bertrand Russell, Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Khmer Rouge, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Ludwig von Mises, Mao Zedong, Markets, Nationalization, Private enterprise, Property, Right politics, Socialism, Soviet Union, Tony Benn

September 13th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Many people still call themselves socialists. But rarely is it made clear what they mean by the description. Few seem aware of its original definition, which persisted from the 1830s to the 1950s. Some will argue that the word has acquired a new meaning since then. Words do change their meanings. But there is no consensus on what that new meaning is.

Despite its idealistic connotations of purity and principle, the word socialism hangs around the neck of left parties. It serves as an invitation for infiltration by Marxists and others, who may enter any party proclaiming their “democratic socialism” or their “socialist principles”.

Having being invited by the s-word, they simply have to point to its original meaning to justify their maximalist stances on class struggle and public ownership. The retention of the s-word will always feed the hard left.

Owenites and Marxists

The term socialist emerged in English for the first time in 1827 in the Co-operative Magazine, which was published in London by followers of Robert Owen. It moved into wider usage in the 1830s. For Owen and his followers, socialism meant the abolition of private property. It also acquired the broader ideological connotation of cooperation, in opposition to selfish individualism.

Robert Owen

As Owen argued in 1840, “virtue and happiness could never be attained” in “any system in which private property was admitted”. He aimed to secure “an equality of wealth and rank, by merging all private into public property”.

Owen and his followers attempted to establish several socialist communities in the UK and USA. All failed within a few years. The young Frederick Engels attended an Owenite meeting in Manchester in 1843, and was inspired by Owen’s notion of socialism.

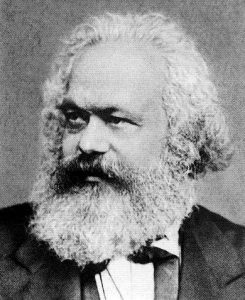

Marx and Engels wanted the complete abolition of the “free selling and buying” of commodities. They advocated common ownership of all means of production and the abolition of commodity exchange and markets.

Hence, from the 1830s until the 1950s, socialism was almost universally defined in terms of the abolition or minimisation of private property and some form of widespread common ownership.

Statist socialism

Marx and Engels insisted that markets should be abolished and all means of production should be placed in the hands of the state.

Karl Marx

Marx and Engels often used the term communism instead of socialism. But this was primarily to distance themselves from the naïve ideas of contemporary socialists rather than to postulate a radically different objective. For them, communism was a label for their movement, rather than their goal. Thus in 1845 they wrote:

Sometimes, as in his Critique of the Gotha Programme of 1875, Marx referred to the “lower” and “higher phases” of communism, instead of socialism.

Sometimes, as in his Critique of the Gotha Programme of 1875, Marx referred to the “lower” and “higher phases” of communism, instead of socialism.

In 1917 Vladimir Ilych Lenin was writing his State and Revolution, on the eve of the Bolshevik seizure of power. Some left critics had argued that Russia was insufficiently developed for socialist revolution.

So Lenin redefined socialism as a transitional stage (still involving extensive state ownership) between capitalism and communism.

By contrast, Marx and Engels did not use the term socialism to refer to a future stage between capitalism and communism. Their aim was described interchangeably as socialism or communism.

French lessons

Engels’ description of Charles Fourier and Claude-Henri de Saint-Simon as “utopian socialists” is inaccurate because – unlike Owen – they supported private ownership of the means of production. They imagined harmonious communities without poverty or strife. But some of Saint-Simon’s followers moved toward socialism.

Philippe Buchez was inspired by Saint-Simon. He promoted worker cooperatives as early as 1831, and his ideas became prominent during the French Revolution of 1848.

Contrary to most of his contemporary socialists and communists, Buchez and his followers eventually recognized the need for multiple, autonomous, worker co-operatives, each owning property and engaging in contracts and markets.

But this tolerance of markets was too much for Marx. In 1875 he described Buchez’s ideas as “reactionary”, “sectarian”, opposed to the workers’ “class movement”, and contrary to the true revolutionary aim of “cooperative production … on a national scale”.

Pierre Joseph Proudhon

In 1840 Pierre Joseph Proudhon published his What is Property? He used both socialism and anarchism to describe his proposed future society. But, like Buchez, Proudhon proposed a system of worker cooperatives linked by contracts and trade. This enraged Marx and Engels, who relentlessly attached Proudhon’s ideas.

Non-statist versions of socialism endured but were overshadowed by statist variants. From the 1870s to the 1950s the dominant view of socialism involved state ownership and control. To emphasise their dissent, Proudhon and other opponents of statist socialism often described themselves as anarchists.

Fabianism

The idea that private property and markets should be abolished was thematic to socialism and unconfined to Marxism. It pervaded the writings of socialists as diverse as Continental revolutionary communists and British Fabians. At least until the 1950s, hostility towards markets and private property were thematic for socialism as a whole. The founding influences of Owen and Marx were long-lasting.

Beatrice & Sidney Webb

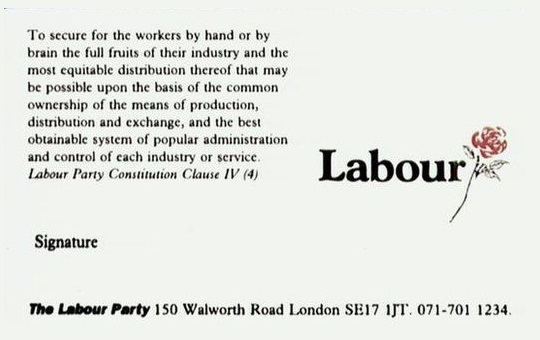

Drafted by leading Fabians Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Clause Four, Part Four of the Labour Party Constitution encapsulated collectivist thinking when it was adopted in 1918:

“To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

This provided for no exception: all production would be in common ownership and there would be no private sector. Although some Labour Party thinkers began to entertain the possibility of some private enterprise, many party members remained resolutely in support of widespread common ownership.

Some Fabian socialists tried to lay out more detail on how socialism would work. The Webbs laid out their ultimate vision of a fully planned and consciously controlled socialist economy where all markets and private ownership of the means of production had been marginalized to insignificance. They wanted private ownership of the means of production to be ended: it was a “perversion”.

They envisaged a massive, complex structure of national, regional and local committees, all involved in decision-making over details of production and distribution. How would these cope with the huge amounts of information and specialized knowledge in modern complex economies? It was simply assumed that this was relatively easy to sort out in some rational manner.

Guild socialism

G D H Cole

The British Fabian G. D. H. Cole is sometimes described as a “libertarian socialist” and as an advocate of “decentralized” or “guild” socialism. But he supported the wholesale nationalisation of industry and the abolition of private enterprise. To his great credit, and unlike most Marxists, Cole did actually try to explain how a future socialist society would work. But his explanation is a failure.

Cole did not show how devolved democracy could function and endure in a society where private property was abolished. His hyper-democratic account of socialism, where individuals make decisions throughout industry as well as the polity, failed to consider the problems of necessary skill in judgment, of obtaining relevant knowledge, and the overwhelming number of meetings and decisions involved.

Cole’s vision of socialism was of an integrated, national system where “a single authority is responsible both for the planning of the social production as a whole and for the distribution of the incomes which will be used in buying it.” Within this “single authority” he also sought devolved worker control. He wanted local autonomy of manufacturing, modelled on the medieval guild.

But Cole was tragically unclear about how the two were to be reconciled. How would the autonomous powers of the latter be protected from the control and centralizing ambitions of the “single authority”? There was no adequate answer. His whole system was unworkable.

Clement Attlee and Bertrand Russell

In 1937, eight years before he became UK Prime Minister, Clement Attlee wrote of the “evils” of capitalism: their “cause is the private ownership of the means of life; the remedy is public ownership.” Attlee then approvingly quoted the words of Bertrand Russell:

“Socialism means the common ownership of land and capital together with a democratic form of government. … It involves the abolition of all unearned wealth and of all private control over the means of livelihood of the workers”.

Bertrand Russell

Even within the moderate and non-Marxist Labour Party, the word socialism endured with these collectivist connotations, posed in opposition to private firms, competition and markets.

Russell represented an important strain of thinking within the British left. He wholeheartedly supported the notion of a publicly-owned and planned economy, but he rejected “Bolshevik methods”.

But is it possible to promote a state monopoly of economic power, while preventing a central-state monopoly and potential despotism of political power? In no historical case has the first happened and the second been prevented. Statist socialism, with viable democracy, political pluralism and effective decentralisation, exits only in the imagination of impractical idealists.

‘Market socialism’?

In the 1930s the economist Oskar Lange and others claimed that mainstream economic theory can show how socialism could work. Lange and his co-workers argued that managers of firms should be instructed to expand production until marginal costs were equal to the declared market price of the product.

Oskar Lange

But this assumed that marginal costs could be calculated and that the central planners could smoothly and readily assess whether there were surpluses or shortages, and adjust prices accordingly. Lange and others wrongly assumed that such information was readily available.

These proposals for “market socialism” attempted to simulate markets within a planning system, rather than to establish true markets with private ownership and commodity exchange. There was no private ownership and no capacity for firms to make contracts. The models developed by Lange and his collaborators involved a high degree of centralised co-ordination that excluded any real-world market.

Significantly, no attempt has ever been made to implement a Lange-type model in reality. Lange himself made no effort to persuade the post-1945 “socialist” government in his native Poland of the value of the idea.

Hence the use of the term “market socialism” in this context is highly misleading. Unlike the proposals of Buchez or Proudhon, and unlike the system of worker cooperatives established under Josip Tito in Yugoslavia after the Second World War, Lange’s proposal did not involve true markets.

Post-war revisionism

In 1956 C. Anthony Crosland published The Future of Socialism. This began Labour’s slow reconciliation with markets, private enterprise and a mixed economy. Signalling an attempted shift of meaning, Crosland argued that the central aim of socialism was not necessarily common ownership, but social justice and economic equality, and these could be achieved by different means. But although his argument was highly influential, it was widely attacked within the Labour Party and elsewhere.

Hugh Gaitskell

In 1959 the (West) German Social Democratic Party abandoned the goal of widespread common ownership. In the same year, Hugh Gaitskell tried to get the British Labour Party to follow this lead, but met stiff resistance. The party did not ditch its Clause Four commitment to the complete “common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange” until 1995.

Richard Toye noted that the Labour Party assumed widespread public ownership and failed to develop adequate policies concerning the private sector:

“Labour, until at least the 1950s, showed little interest in developing policies for the private sector. During the 1960s, the party demonstrated continuing ambiguity about whether or not competition was a good thing. This ambiguity continued at least until the 1980s.”

Tony Blair and New Labour

But in 1995, after 77 years, Labour’s Clause Four was changed. Tony Blair successfully ended the Labour Party’s longstanding constitutional commitment to far-reaching common ownership. But this was not without opposition. Tony Benn protested: “Labour’s heart is being cut out”.

Tony Blair

The new wording of “Clause IV: Aims and Values” declared that: “The Labour Party is a democratic socialist party.” But the clause ceased to promote unalloyed common ownership and the full text admitted a positive role for markets and a private sector.

By contrast, the 1918 formulation did not use the word socialism – it had undiluted common ownership instead.

Blair introduced the word socialism in 1995, but he attempted to change its meaning. He promoted “social-ism”, which now meant recognizing individuals as socially interdependent. It also signalled social justice, cohesion and equality of opportunity, within a mixed economy involving both private and public ownership.

Hence, instead of tackling the problem of Labour’s old collectivist DNA more directly, Blair tried to change the meaning of socialism and to airbrush Labour’s history. He failed to promote an adequate alternative vision or philosophy within Labour to replace old-fashioned common ownership. To the traditional left, it appeared as the substitution of purity and socialist principle by fudge and capitalist compromise.

But oddly Blair was responsible for the explicit insertion of socialism in its aims. This inadvertently played into the hands of the party’s enduring, backward-looking left.

Learning no lessons

Blair’s invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the financial crash of 2008 helped to turn the Labour membership against Blair and his compromises with capitalism. As evidence of the Freudian defence mechanism of regression as a response to severe stress, Labour reverted to an earlier stage of its history, re-adopting its infant ideological comforts of collectivism and state control.

The ghost of Tony Benn emerged. His Campaign Group in parliament moved from the margins to the party mainstream.

Like Benn, the current leadership of the UK Labour Party shows little awareness of the chronic problems of managing a modern, complex, centrally-planned economy. They now accept a “mixed economy” as a transition stage, but fail to promote the virtues or enduring role of the private sector.

Jeremy Corbyn

To take one example, Jeremy Corbyn’s 2015 address to the UK Co-operative Party is overwhelming in its blandness and naivety. Therein Corby shows no awareness that viable and meaningful decentralisation of economic power must involve (cooperative or other) firms with the right to own, set prices for, and trade their outputs. He rightly mentions the virtues of worker and consumer participation in decision-making, but shows no awareness of the practical limits of such participation.

Corbyn simply waved the magic wand of “democracy” without any apparent appreciation that it is impossible to involve everyone in more than a tiny fraction of all the complex decisions involved in any modern economy. Corbyn showed no awareness of the practical problems of complex decision-making in large organisations, which are dependent on multiple, localised, skills and expertise.

Withering socialism

Following Labour’s advances in the 2017 general election, the leadership of Corbyn and his allies seems entrenched. Recently they have gained control of the powerful National Executive Committee of the party. For future nominations for the Labour leadership or deputy leadership, it is probable that the 15 per cent threshold of support from Labour MPs will be lowered, making ongoing hard left prominence more likely.

In the 1980s and 1990s the hard left were pushed back with the help of large, moderate trade unions that were affiliated to Labour. Those countervailing forces have gone. The unions are smaller and some are more inclined to the hard left.

With the Brexit vote in 2016, Britain has entered its most dangerous political crisis since the Second World War. The country is governed by an inept Conservative Party that is tearing up the UK constitution and concentrating unprecedented power in the hands of its duplicitous ministers.

With the Brexit vote in 2016, Britain has entered its most dangerous political crisis since the Second World War. The country is governed by an inept Conservative Party that is tearing up the UK constitution and concentrating unprecedented power in the hands of its duplicitous ministers.

Labour’s 2017 electoral advances were partly due to Tory incompetence. In this volatile climate it is possible that Corbyn could soon become prime minister. Subsequently, an obvious danger would be that the concentration of executive power legislated by Tory opponents would prove too tempting for Labour in power to relinquish. After growing authoritarianism from the reactionary right, we might experience a new, collectivist authoritarianism from Labour.

A Labour government committed to dealing with the severe crises in the health, education and housing sectors can bring positive benefits. Substantial state intervention is needed to regulate markets, especially in the area of finance. But such a programme needs to be tempered by heavy measures of pragmatism, pluralism, cautious experimentation and ideological humility that are alien to the current leadership.

They show no sign that they have abandoned their old, statist socialism. There is no recognition that markets and substantial private enterprise are necessary to sustain autonomy and decentralisation. As has become apparent in Corbyn’s favourite socialist experiment in Venezuela, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

Conclusion – More French lessons

However outdated, it is difficult to dislodge the core principles upon which any party is founded. France provides an important illustration. Michel Rocard was a leading member of the French Socialist Party and a prime minister under François Mitterand. He long argued that French socialists

Emmanuel Macron

had failed to modernise and to accept the enduring importance of private property and markets.

Emmanuel Macron was a protégée of Rocard. Macron gained presidential power after breaking from the fractured Socialist Party and building a powerful centre force. Perhaps there are some lessons for progressives in Britain. It would not be the first time that the French have shown us the way forward.

13 September 2017

Minor edits: 16, 21 September 2017

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Attlee, Clement R. (1937) The Labour Party in Perspective (London: Gollancz).

Bestor, Arthur E., Jr (1948) ‘The Evolution of the Socialist Vocabulary’, Journal of the History of Ideas, 9(3), June, pp. 259-302.

Blair, Tony (1994) Socialism, Fabian Pamphlet 565 (London: Fabian Society).

Cole, George D. H. (1920) Guild Socialism Re-Stated (London: Parsons).

Crosland, C. Anthony R. (1956) The Future of Socialism (London: Jonathan Cape).

Harrison, J. F. C. (1969) Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Owen, Robert (1991) A New View of Society and Other Writings (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Landauer, Carl A. (1959) European Socialism: A History of Ideas and Movements from the Industrial Revolution to Hitler’s Seizure of Power, 2 vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Lange, Oskar R. and Taylor, Frederick M. (1938) On the Economic Theory of Socialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

Proudhon, Pierre Joseph (1890) What is Property?: An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government, translated from the French edition of 1840 (New York: Humbold).

Russell, Bertrand (1920) The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Steele, David Ramsay (1992) From Marx to Mises: Post-Capitalist Society and the Challenge of Economic Calculation (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court).

Toye, Richard (2004) ‘The Smallest Party in History’? New Labour in Historical Perspective’, Labour History Review, 69(1), April, pp. 83-104.

Webb, Sidney J. and Webb, Beatrice (1920) A Constitution for the Socialist Commonwealth of Great Britain (London: Longmans Green).

Posted in Bertrand Russell, Brexit, Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Labour Party, Left politics, Lenin, Markets, Nationalization, Private enterprise, Robert Owen, Socialism, Tony Benn, Tony Blair, Tony Blair, Venezuela

May 8th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

This is in part a personal memoir – concerning my role in a minor episode in political history. More importantly, it has lessons concerning Labour’s ideological inertia – the difficulty of modernising the party and bringing it from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century.

Socialism and Labour’s Clause Four

Both Robert Owen and Karl Marx defined socialism as “the abolition of private property”. This kind of collectivist thinking was encapsulated in Clause Four, Part Four of the Labour Party Constitution when it was adopted in 1918:

“To secure for the workers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry or service.”

This provided for no exception: all production would be in common ownership and there would be no private sector. Although some Labour Party thinkers began to entertain the possibility of some private enterprise, many party members remained resolutely in support of widespread common ownership.

Clement Attlee

In 1937, eight years before he became Prime Minister, Clement Attlee approvingly quoted the words of Bertrand Russell: “Socialism means the common ownership of land and capital together with a democratic form of government. … It involves the abolition of all unearned wealth and of all private control over the means of livelihood of the workers.”

After 1945, the position of many leading Labour Party members began to shift. First the realities of gaining and holding on to power – as a majority party for the first time – dramatized the political and practical unfeasibility of abolishing all private enterprise. Some nationalization was achieved, but a large private sector remained.