Category: Neoliberalism

August 19th, 2018 by geoffhodgson1946

More on the Seven Dimensions of Liberalism

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

The common core of all varieties of liberalism is the stress on individual liberty and universal rights, including the rights to private property and to freedom of expression. These universal rights and liberties require equality under the law, under a competent legal system that protects rights and pursues justice.

In a previous blog I laid out Seven Dimensions of Liberalism. The present blog extends that analysis by considering different varieties of liberalism within this seven-dimensional space. I contrast what (in forensic mood) might be described as neoliberalism with what I call liberal solidarity.

Classical liberalism

There are several possible names come to mind as possible labels for the highly varied constituent territories of liberalism. Terms such as classical liberalism, new liberalism, social liberalism, neoliberalism and libertarianism should be considered. But all these labels have their problems.

Adam Smith

Consider classical liberalism. This is typically applied to foundational liberal thought from John Locke, through Adam Smith and Jeremy Bentham to John Stuart Mill. But there are profound divisions within classical liberalism.

Thomas Paine’s pursuit of measures to reduce inequality is unmatched by his liberal contemporaries.

Adam Smith’s emphasis on the importance of “moral sentiments” and justice contrasts greatly with the reductionist-utilitarian approaches developed by Hume and Bentham and adopted (albeit with reservations) by Mill.

Apart from the emphasis on individual rights including private property, the classical liberals agreed on the need for a small state. But they lived in a period when the state and its tax levels were much smaller than they became in the twentieth century.

We cannot automatically assumed that they would have taken the same small-state view in the present context, especially if they were responsive to practical experiment and historical experience.

Consequently, classical liberalism does not denote one distinctive type or phase of liberalism. The original Liberalism from the seventeenth to the mid-nineteenth century contained widely diverging variants.

New liberalism and other labels

A major turn in liberal thought was foreshadowed by Mill and developed in the later decades of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century by Thomas H. Green, Leonard T. Hobhouse and John A. Hobson in the UK, and in the US by Lester Frank Ward, John Dewey and others.

These “new liberals” saw individual liberty as something achievable only under favourable social and economic conditions. Poverty and ignorance were barren soils for individual freedom and fulfilment. They argued that individual flourishing required the development of an education system, a welfare state and other state action to reduce unemployment and poverty.

John A Hobson

Thinkers such as Green, Hobhouse, Hobson, Ward and Dewey have been described as new liberals. But their ideas are no longer new and the label is in little use today. It also risks confusion with the now-ubiquitous and over-stretched swear-word of neoliberalism.

Social liberalism is another term that has been to describe the strain of liberal thinking – from Green to Dewey – that pursued greater state intervention and a welfare state.

But a problem with this label lies in the multiple meanings of the word social. Many used social liberalism to signal an emphasis on the need for cooperation between individuals through social arrangements to further human fulfilment. The word social here is used in a broad and inclusive sense.

An alternative understanding of social is exclusive: social is regarded as an antithesis to economic. This commonplace but problematic dichotomy contrasts the economic sphere of business and profit-seeking with the social sphere of the family, non-market relations, reciprocity and so on.

This enabled an alternative interpretation of social liberalism as liberalism applied to the narrowly-conceived social sphere. It would involve, for example, the promotion of homosexual rights and the decriminalization of the use of recreational drugs. Worthy as those aims may be, this is a much narrower agenda than that promoted by social liberalism in the broader sense.

Another option is the word solidarism. Inspired by Émile Durkheim and Léon Bourgeois, ideas emerged in France that were similar to and at about the same time as the new liberalism of Hobhouse and Hobson in Britain.

The solidarists criticized extreme laissez-faire and argued that individuals had a debt to society as a whole, which should be repaid through taxation and social welfare schemes. But solidarism in France took a distinctive form, putting more limited emphasis on state intervention than the proposals of some of their British counterparts.

Ambiguities of social democracy

A final term to be considered here is social democracy. This has shifted more successfully in meaning than socialism, but originally they amounted to more or less the same thing. Many of the early social democratic parties were led by Marxists, including the important Social Democratic Workers’ Party of Germany, founded in 1869. Although some social democrats favoured peaceful reform rather than violent revolution, at that time they mostly agreed on the goal of large-scale common ownership.

Harold Wilson

During the twentieth century the usage of the term social democracy shifted radically. After the Second World War it came to mean the promotion of greater economic equality and social justice within a capitalist economy. It also connoted a political strategy orientated toward the interests of the trade unions and the working class.

The term social democracy still carries this historical and strategic baggage. It has been eschewed by some because of its links with socialism. Others argue that its strategic, class-orientated vision has become obsolete. Another problem is that the word social does not make a clear addition to democracy, which few would oppose.

Post-war social-democratic policies are challenged by the fragmentation of their traditional base in the organized working class and by the heightened forces of globalization.

Consequently, while a reformed and reinvigorated social democracy may have some mileage, I suggest we consider the alternative term liberal solidarity to describe an important zone within liberalism. We should examine its principles and its agenda for reform. But first it is necessary to deal with the tricky label and substance of neoliberalism.

Original diversity within the Mont Pèlerin Society

The Mont Pèlerin Society changed in substance and direction. It began under a different name in the 1930s and was first convened under its current name in 1947. It was then an attempt to convene different kinds of liberals in defence of a liberal market economy, just after the defeat of fascist tyranny, during an expansion of Communist totalitarianism, and while witnessing the rise of statist socialist ideas in Western Europe and elsewhere. Liberalism broadly was on the rocks: it needed its defenders.

Michael Polanyi

Michael Polanyi (the brother of Karl Polanyi) advocated Keynesian macroeconomics in a market economy, alongside a radical redistribution of income and wealth. He rejected a universal reliance on market solutions, seeing it as a mirror image of the socialist panacea of planning and public ownership. He did not mince his words against this “crude Liberalism”:

“For a Liberalism which believes in preserving every evil consequence of free trading, and objects in principle to every sort of State enterprise, is contrary to the very principles of civilization. … The protection given to barbarous anarchy in the illusion of vindicating freedom, as demanded by the doctrine of laissez faire, has been most effective in bringing contempt on the name of freedom … .”

Although he attended the first meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society, Polanyi had drifted away by 1955, stressing its inadequate solutions to the problem of unemployment and its promotion of a narrow view of liberty as the absence of coercion, neglecting the need to prioritize human self-realization and development.

In its early years, the Mont Pèlerin Society hosted debates on the possible role of the state in promoting welfare, on financial stability, on economic justice, and on the moral limits to markets. Like Polanyi and other early members of the society, Wilhelm Röpke argued that the state was necessary to sustain the institutional infrastructure of a market economy. The state should serve as a rule-maker, enforcer of competition, and provider of basic social security. Röpke’s ideas were highly influential for those laying the foundations of the post war West German economy.

While they received a more sympathy from Hayek, Ludwig Mises regarded Röpke’s views as “outright interventionist”. Mises became so frustrated with these arguments in favour of a major role for the state that he stormed out of a Mont Pèlerin Society meeting shouting: “You’re all a bunch of socialists.”

The rise of modern neoliberalism

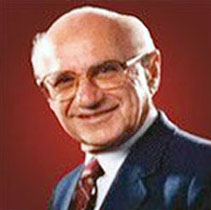

Angus Burgin’s history of the society shows how its early period of relative inclusivity was followed by schisms, departures, and a narrowing of opinion. People like Polanyi and Röpke became inactive. Eventually the primary locus of the Mont Pèlerin Society shifted to the US, with greatly increased corporate funding under the rising intellectual leadership of Milton Friedman.

Milton Friedman

Hence the Mont Pèlerin Society evolved from a broad liberal forum to one focused on promoting a narrow version of liberalism that is more redolent of Herbert Spencer than of Adam Smith, Thomas Paine or John Stuart Mill. This ultra-individualist liberalism entailed a narrow definition of liberty as the absence of coercion, it relegated the goal of democracy, it neglected economic inequality, it overlooked the limits to markets, it saw very limited grounds for state welfare provision and intervention in financial markets, and it stressed self-interest rather than moral motivation.

But in the seventh dimension it tolerated a multiplicity of positions, as exemplified by Friedman’s opposition to the Iraq War. In all of the seven dimensions of liberalism, the post-1970 position of the Friedman-led Mont Pèlerin Society was redolent of Spencer, but without some of the latter’s Victorian idiosyncrasies. In the first six dimensions, this post-1970 neoliberalism is very different from liberal solidarity.

It is only after the 1960s that the Mont Pèlerin Society acquired a narrower identity, which at a pinch might be described as neoliberalism. Here Mirowski is onto something: “Neoliberals seek to transcend the intolerable contradiction by treating politics as if it were a market and promoting an economic theory of democracy.” In other words this neoliberalism reduces, all of politics, law and civil society as markets, and are analysed using market categories.

Neoliberalism’s affinity with Marxism

This neoliberalism has an odd similarity with Marxism, despite other major differences in theory and policy. Marx and Engels also reduced civil society to economic matters of money and trade. Marx wrote in 1843: “Practical need, egoism, is the principle of civil society … The god of practical need and self-interest is money.”

Karl Marx

Civil society, for Marx, was the individualistic realm of money and greed. Hence Marx concluded that “the anatomy of civil society is to be sought in political economy.” The analysis of the political, legal and social spheres was to be achieved with an economics based on the assumption of individual self-interest.

Furthermore, the state, law and politics under capitalism were made analytically subservient to this dismembered, economistic vision of civil society.

Accordingly, Frederick Engels wrote in 1886 that under capitalism “the State – the political order – is the subordinate, and civil society – the realm of economic relations – the decisive element.” Everything was deemed a matter of greed and commerce, to be understood through economic analysis.

Hence, in its theory of capitalism, classical Marxism was a harbinger of modern neoliberalism, reducing everything to market relations. There was no defence of civil society in its own right.

When attempts were made to build socialism on Marxist principles, not only markets were minimized but also civil society was virtually destroyed. Before 1989, the restoration of civil society was one of the foremost demands of the dissident movements in Eastern Europe.

Certainly there are more sophisticated and less reductionist treatments by Marxists of civil society and the state, not least by Antonio Gramsci. But Marx and Engels, alongside some neoliberals, embraced economic reductionism. Everything turns into the economics of trade, eclipsing the autonomy of politics and law, and neglecting the vital importance of non-commercial interaction and association within civil society.

Neoliberalism versus liberal solidarity

On these vital issues, liberal solidarity stresses its differences from both neoliberalism and classical Marxism. It does not treat the individual purely as a self-interested, market-oriented maximizer. It is committed to democracy as a distinctive source of legitimation for government, and a means of individual and social development (dimension 2), not as a marketplace for power.

Liberal solidarity stresses the feasible and moral limits to markets (dimension 4). It upholds a view of the individual that combines measures of self-interest with a moral concern for justice and fairness (dimension 6). On all these points it is distinct from these other doctrines.

Today, liberal solidarity must emphasise its radical differences from both post-1970 neoliberalism and from Marxism. This is made extremely difficult in a leftist intellectual context when any defence of markets or private enterprise, to any extent or degree, is pushed aside as neoliberal. Current cavalier uses of the term do much more harm than good.

Many so-called anti-neoliberals are also anti-liberals. They prioritize neither liberty nor freedom of expression. They offer no defence of private enterprise or markets, to any extent or in any form. They promote a state-dominated economy, which we know from history will always threaten freedom and human rights. They believe they are principled. They may have good intentions. To quote from their mentor Lenin: “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” But as Marxists fail to understand, the only principled and effective defence of human rights is some form of liberalism.

Liberalism has to be fortified, but not in all of its forms. Liberal solidarity is the radical alternative to the illiberal or undemocratic populisms of the left or right. It can address the problems created by large corporate interests, by the power of undemocratic capitalist technocrats or by incipient dictatorships. It emphasises the importance of markets and private property, but without regarding them as universal panaceas. It retains uppermost the importance of human rights and human cooperation, with the goal of human flourishing and social development.

19 August 2018

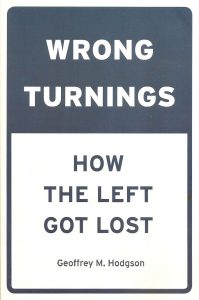

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

References

Burgin, Angus (2012) The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press). See pp. 16, 80-86, 121.

Jacobs, Struan and Mullins, Phil (2016) ‘Friedrich Hayek and Michael Polanyi in Correspondence’, History of European Ideas, 42(1), pp. 107-30.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Frederick (1962) Selected Works in Two Volumes (London: Lawrence and Wishart). See vol. 1, pp. 362, 394-5.

Marx, Karl and Engels, Frederick (1975) Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works, Vol. 3, Marx and Engels: 1843-1844 (London: Lawrence and Wishart). See p. 172.

Mirowski, Philip (1998) ‘Economics, Science and Knowledge: Polanyi vs. Hayek’, Tradition and Discovery: The Polanyi Society Periodical, 25(1), pp. 29-42.

Mirowski, Philip (2009) ‘Postface: Defining Neoliberalism’, Mirowski, Philip and Plehwe, Dieter (eds) (2009) The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press), pp. 417-55. See p. 456.

Mirowski, Philip (2013) Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown (London and New York: Verso). See p. 71.

Polanyi, Michael (1940) The Contempt of Freedom: The Russian Experiment and After (London: Watts). See pp. 35 ff., 57-58.

Polanyi, Michael (1945) Full Employment and Free Trade (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). See pp. 142-6.

Polanyi, Michael (1951) The Logic of Liberty: Reflections and Rejoinders (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul).

Posted in Democracy, Karl Marx, Left politics, Lenin, Liberalism, Ludwig von Mises, Markets, Michael Polanyi, Neoliberalism, Philip Mirowski, Private enterprise, Property, Right politics, Socialism

August 1st, 2018 by geoffhodgson1946

Beyond its shared stress on liberty and rights, liberalism comes in many different forms. One of these varieties is liberal solidarity.

All versions of liberalism stress individual liberty and universal rights, including the rights to private property and to freedom of expression. These universal rights and liberties require equality under the law, under a competent legal system that protects those rights and pursues justice.

Original conservativism differs from liberalism because it stresses established or religious authority and tradition over rights. Socialism generally differs from liberalism because it downgrades the right to private property. But there is no historical case where personal and civil liberties have existed without extensive rights of private property.

Statist socialism further differs from liberalism also because it concentrates politico-economic power in the hands of the state, thus undermining countervailing power, which is necessary to sustain democracy and individual rights. Marxism differs from liberalism to an even greater degree, because it regards all liberal rights as bourgeois: it rejects the idea of universal individual rights in favour of the class rule of the proletariat.

Liberalism was broadly defined in its struggles against despotism. But once autocracy is removed, and freedom and legal equality are established, then liberalism as a whole lacks a further common purpose, other than the preservation or consolidation of those liberal gains. At this point, the wide liberal coalition divides into multiple zones, exploring different districts of their spacious common territory, and falling on different sides of key dilemmas.

Hence the Enlightenment triumph of liberalism gave way to rival liberalisms, each stressing different priorities or visions of the future. These differences range across multiple dimensions in conceptual hyperspace.

While exploring seven dimensions of this hyperspace, I accent a particular variety of liberalism that I call liberal solidarity.

The seven dimensions

Consider the following seven vital dilemmas:

1. Broad versus narrow conceptions of liberty.

The narrow definition of liberty, promoted by Freidrich Hayek and Milton Friedman among others, is the absence of coercion. Other liberals – including John Stuart Mill, Michael Polanyi, Isaiah Berlin and Amartya Sen – argued that this is insufficient. They asked us to consider the conditions enabling the individual to appraise his or circumstances and then to act freely, typically in cooperation with others. These conditions constitute positive or public liberty, in contrast to the negative or private liberty provided by the absence of coercion. As well as the capacities for choice and action, some writers argue that liberty is also about the opportunities for self-development and for human flourishing.

2. Degrees of commitment to representative political democracy.

Most liberals support representative political democracy, as long as it does not overturn basic human rights, including the rights of minorities. But some liberals, such as Ludwig Mises and Hayek, have regarded democracy as dispensable under specific conditions, believing that the preservation of private property and markets are more important. The counter argument is that democracy is strongly correlated with economic development, the protection of human rights, and the absence of war and famine. Hence democracy is vital for a healthy, tolerant and open society.

3. Degrees of emphasis on economic equality.

Thomas Paine was a liberal who stressed the interdependence of individuals in a free society. Hence, given our debt to others, we are obliged to pay taxes for the common good. Also John Stuart Mill argued there should be some redistribution of inherited wealth. Against libertarian individualists, many liberals defend responsible trade unions as a way of empowering working people and reducing inequality. These are cases of liberal solidarity rather than atomistic individualism.

4. Possible limits to choice and markets.

While liberals generally stress the importance of individual choice, in both trade and politics, some also stress the practical and moral boundaries to contracts and to markets. Today we condemn the holding and trading of slaves. For democracy to be uncorrupt, there should not be markets for the votes of ordinary people or politicians. Other market arrangements are challengeable, on moral or practical grounds, suggesting that contracts and markets are not the solution to every problem.

5. Grounds for state intervention and a welfare state.

Some liberals, including John A. Hobson and John Dewey, saw the provision of adequate healthcare and education as vital for individual self-determination and flourishing. Individuals should also be as free as possible from the anonymous coercions of ignorance, destitution and illness. Hence the liberals David Lloyd George and William Beveridge built the foundations of the welfare state in the UK. John Maynard Keynes pointed to the need for the state to intervene to prevent financial crashes and minimize unemployment. Many modern liberals also accept the legitimacy of judicious state action to mitigate climate change.

By the above five criteria, liberal solidarity recognizes liberty as more than the absence of coercion, defends political democracy, attempts to reduce extremes of economic inequality, and conceives of a larger role for the state than small-state versions of liberalism. It promotes a mixed economy including some public ownership and a variety of forms of private enterprise. The mixture would include worker cooperatives (which are the most viable positive legacy of small socialism).

Liberal solidarity counters the original liberal emphasis on minimal government. Some state intervention is necessitated by the limitations of markets and by growing complexity. Nevertheless, all liberals acknowledge the dangers of excessive bureaucracy and concentrations of state power, and they call for mechanisms of scrutiny and accountability, as well as for countervailing powers.

6. Self-interest versus cooperation and morality.

Several liberals have argued that social order emerges out of the interactions of self-interested, pleasure-maximizing individuals. But this is not a universal view among liberals. While recognizing the selfish aspects of human nature and the incentives they offer for trade and innovation, many liberals stress the importance of morality, justice or duty. They argue that adequate social cohesion cannot be achieved on the basis of selfishness alone. Adam Smith expressed this view: he was not an unalloyed advocate of individual selfishness. Charles Darwin – who politically was a liberal – explained how, alongside a measure of self-interest, morality and cooperation were products of human evolution, and thus part of our nature. Hobson took up this Darwinian view, also underlining the importance of moral motivation. Relatedly, Keynes saw the Benthamite utilitarian calculus of pleasure-seeking, as “the worm which has been gnawing the insides of modern civilisation and is responsible for the present moral decay.” The motivational bases of liberal solidarity are morality, sympathy and justice, and not simply personal satisfaction or self-interest.

7. Nationalism versus internationalism and openness.

Like socialism and conservativism, liberalism has been divided on questions of foreign policy. Socialists, conservatives and liberals have argued for and against specific wars, for or against imperialism or colonialism, for or against the idea of exporting favoured institutions by invading other countries with armed force. They have also been internally divided on immigration policy, advocating different degrees of restriction or free movement.

Addressing dimension six, liberal solidarity emphasises our potential for cooperation and moral judgment, rather than focusing on self-interest alone. In regard to dimension seven, liberal solidarity opposes imperialism and colonialism. It stresses the importance of social inclusion and the benefits of free movement.

Liberals, Conservatives and Republicans

From the beginning of the twentieth century, in the UK and the US, liberalism became more interventionist. Versions of liberalism prominent in the UK and US are closer to liberal solidarity than some variants in Continental Europe.

When unfettered-market, minimal-state versions of liberalism re-emerged in the UK and US, and became more prominent in the 1970s, they had to find different homes. They took over the Conservative Party in the UK and the Republican Party in the US. Hence Margaret Thatcher was elected as a Conservative Prime Minister in 1979 and Ronald Reagan as a Republican President in 1980. In some their ideas they sounded like nineteenth-century liberals: Whigs became Tories.

When unfettered-market, minimal-state versions of liberalism re-emerged in the UK and US, and became more prominent in the 1970s, they had to find different homes. They took over the Conservative Party in the UK and the Republican Party in the US. Hence Margaret Thatcher was elected as a Conservative Prime Minister in 1979 and Ronald Reagan as a Republican President in 1980. In some their ideas they sounded like nineteenth-century liberals: Whigs became Tories.

But their adoption of unfettered-market ideology was partial, and often compromised when traditional conservative values were threatened. Supported by Thatcher, Reagan ramped up military spending. Their nationalism was heightened when it came to foreign policy and international trade. They retained restrictions on recreational drugs or prostitution. They stressed ‘family values’ as much as rampant individualism.

Like others, these two parties are coalitions, involving unfettered-marketeers, nationalists and traditional conservatives. The election of Donald Trump as US President in 2016 shows the strength of the conservative and nationalist strain among Republicans. Trump is no liberal: he advocates torture, attacks minorities, threatens the press, imposes tariffs and pursues a version of economic nationalism.

Thatcher and Reagan overlooked the absence of democracy in Augusto Pinochet’s Chile and in Apartheid South Africa, and supported stronger military and executive powers. As Andrew Gamble put it, Thatcher and Reagan promoted a ‘free economy and a strong state’.

Thatcher and Reagan were inspired by leading intellectuals such as Hayek and Friedman, who had been working for decades to restore the influence of unfettered-market liberalism. But neither Hayek nor Friedman fits exactly into the Thatcher-Reagan mould. Friedman, for example, advocated the decriminalization of drugs and opposed compulsory military service. He also opposed the Gulf War of 1990-1991 and the Iraq Invasion of 2003.

Hayek voiced partial support for a welfare state. Although he did not support redistributive taxation to reduce inequality, he advocated legislation to limit working hours, state assistance for social and health insurance, state-financed education and research, a guaranteed basic income, and other welfare measures. At least once, Hayek also accepted Keynesian-style, counter-cyclic government strategy to deal with fluctuations in economic activity. Consequently there was some significant difference between Hayek and other libertarians.

Challenges for liberal solidarity

Having set out the large, seven-dimensional hyperspace and explored a few of the important positions within it, it is clear that the depiction of liberalism as broad church is an understatement. The potential variation within liberalism is huge. That is both an asset and a problem. Each variety of liberalism faces the difficulty of distinguishing itself from others. We need to subdivide liberalism’s massive territory if we are to navigate and explore different positions. Each important position within the large space needs to be differentiated from others.

A later blog will further explore the seven-dimensional hyperspace of liberalism and develop the case in favour of liberal solidarity. I shall also show a dramatic contrast with what is often described as neoliberalism.

1 August 2018

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Gamble, Andrew (1988) The Free Economy and the Strong State: The Politics of Thatcherism (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

Posted in Democracy, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Michael Polanyi, Neoliberalism, Private enterprise, Property

July 9th, 2018 by geoffhodgson1946

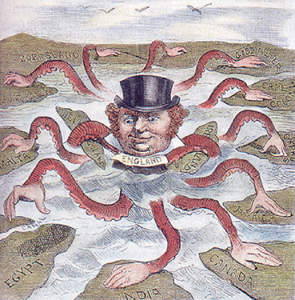

Despite their declared support for free trade, Tory libertarians like David Davis and Jacob Rees-Mogg are acting as if there were still a British Empire.

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

The Brexiteers in the Tory Party do not understand the mechanics of modern trade and have no viable blueprint for Brexit.

Substantial harmonization of standards and regulations is required when trade crosses international borders. The EU Single Market enables massive gains from trade within a harmonized system of regulation. EU member states have a say in the development of those regulations, within a common system.

Outside the EU, the UK would have to replace a huge apparatus of EU-wide regulation that has grown up since 1973 when it joined. This regulatory legislation would be an even more formidable burden than any increased tariff levels that would be adopted if the UK leaves the EU Customs Union and Single Market.

Outside the EU, the UK would have to replace a huge apparatus of EU-wide regulation that has grown up since 1973 when it joined. This regulatory legislation would be an even more formidable burden than any increased tariff levels that would be adopted if the UK leaves the EU Customs Union and Single Market.

This problem creates a dilemma for libertarians who distrust all state machines – especially large ones outside their national comfort zone. Hence, alongside nationalists and hard left socialists, libertarians were in the intellectual forefront of the 2016 Brexit vote in the UK, chiming in with overblown complaints about Brussels bureaucracy, made more strident because this bureaucracy spans national boundaries and is staffed by foreigners.

Some of these libertarians are atomistic individualists, unable to accept that markets consist of more than individuals in isolation. These libertarians are seemingly unaware that all trade and markets must involve commonly accepted rules, as well as the wills and assets of individuals. Markets, in short, are social institutions.

Entering or leaving markets requires dealing with systems of rules. In practice, exit from the EU Single Market means either that regulations have to be developed independently, thus reducing trade possibilities, or that EU regulations have to be accepted for future trade, while having little say in their formation.

The libertarian dilemma

Minimal-state libertarians are thus caught in a dilemma. They have either to accept the adjudications of a foreign court, thus dramatically violating their characteristic anti-state position, by accepting not only state legal system but one outside their homeland, or they have to curtail their cherished ideological ambitions for free trade and markets across national boundaries.

More generally, any contract between sellers and buyers across international boundaries requires agreement on the means of adjudication, if a dispute arises over its terms or fulfilment. Typically it is agreed that disputes will be resolved in the courts of one nominated country. The European Court of Justice was set up to deal with contractual disputes within the EU, and between EU traders and contracting businesses located outside the EU.

More generally, any contract between sellers and buyers across international boundaries requires agreement on the means of adjudication, if a dispute arises over its terms or fulfilment. Typically it is agreed that disputes will be resolved in the courts of one nominated country. The European Court of Justice was set up to deal with contractual disputes within the EU, and between EU traders and contracting businesses located outside the EU.

Regulatory harmonization and trade dispute adjudication create problems for libertarians. Just as big socialists believe in a fantasy world where the state can do everything, some libertarians believe in the obverse fantasy of a minimal state, where trade somehow operates without an extensive state legal infrastructure. As Jamie Peck put it, these “neoliberals” espouse “a self-contradictory form of regulation-in-denial”.

Nevertheless, when faced with the real world of business and contract, these libertarians acquiesce with the state machine and its legal system within their own national boundaries. Their nationalism means that they can live with that outcome.

But when trade crosses international boundaries, the problems of regulatory harmonization and dispute adjudication compel these libertarians to accept – especially when trading with a larger economic bloc – that disputes may have to be resolved in courts outside their national boundaries.

For closet nationalists in libertarian clothing, accepting the judgments of a foreign court is a step too far. The lenience granted to their national courts is not granted to those of foreigners.

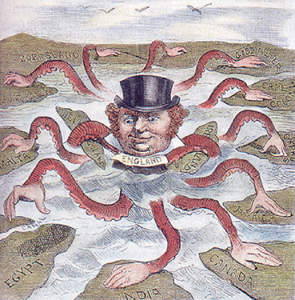

Bring back the British Empire – and other fantasies

British nationalists in libertarian clothing may then call up another fantasy from the past. They can imagine that Britain is still a great power, and that it has the capacity to compel that all trade disputes be resolved in British courts. In their imagination these libertarians bring back the British Empire. Imperial power makes everyone else a rule-taker. They may talk of that bygone world in the corridors of Eton, but it is far beyond the reality of global power today.

Across the Atlantic, American nationalists in libertarian clothing perform ideological gymnastics by allying themselves with politicians such as Donald Trump. He an economic nationalist rather than an advocate of international free trade. As long as these dubious libertarians can concentrate their gaze on the domestic US market and avoid the world beyond, then with some additional fantasising they might continue to believe in their myth of a minimal state.

Instead of the Empire, a US national fantasy is the Wild West. Historically, this was a short-lived zone, partly out of reach of the state and its system of law. Deals were done, aside the barrel of a gun. It is the US version of a mythological libertarian paradise. Global reality today, however, is very different.

A third fantasy is the idea of Jeremy Corbyn that Britain can leave the EU and build socialism. This is a mythical as the other fantasies. Corbyn does not understand markets and has no viable blueprint either – but that is the subject of other blogs. In the meantime, we note that all these efforts to leave the EU are based on fantasies that have little connection to the world in which we live today.

9 July 2018

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

References

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2018) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Peck, Jamie (2010) Constructions of Neoliberal Reason (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press). See p. xiii.

Posted in Brexit, Donald Trump, Jeremy Corbyn, Left politics, Liberalism, Markets, Neoliberalism, Populism, Property, Right politics, Socialism, Uncategorized

June 1st, 2018 by geoffhodgson1946

Stretching the word “neoliberal” to cover people as different as Deng Xiaoping and Donald Trump has turned it into an absurdity.

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Once upon a time, the word neoliberalism might have been confined to an extreme form of individualism that eschews state regulation, promotes economic austerity and a minimal state, opposes trade unions and vaunts unrestrained markets as the solution to all major politico-economic problems.

But today the usage of the word neoliberalism is no longer so restricted. I have been told more than once that anyone who is not a socialist is automatically a neoliberal. Any defence of the existence of markets now risks quick rejection with an angry neoliberal stamp upon it.

More frequently these days, a wide range of politicians, from Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan at one extreme, to Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, Emmanuel Macron and Tony Blair at the other limit, are all described as neoliberals, despite, for example, hugely varied policies on taxation, government expenditure and the role of the state.

In their book on Neoliberalism, Damien Cahill and Martijn Konings describe the US President Donald Trump as a neoliberal. Yet he is a supporter of protectionism and he has imposed import tariffs: he does not believe in free trade. The word neoliberal is now stretched beyond credence and coherence.

Sneaky Deng Xiaoping was a neoliberal

Guardians of socialist purity have described some errant Marxist or socialists as neoliberals. In his Brief History of Neoliberalism, Marxist academic David Harvey described revisionist-Marxist Deng Xiaoping as a neoliberal.

From 1978, Deng supported the reintroduction of markets into the Chinese economy. But he still proposed a strong guiding hand by the state, including centralized management of the macro-economy and the financial system.

Harvey admitted that Deng’s policies led to strong economic growth and “rising standards of living for a significant proportion of the population” but he passed quickly over this ellipsis.

Harvey admitted that Deng’s policies led to strong economic growth and “rising standards of living for a significant proportion of the population” but he passed quickly over this ellipsis.

In fact, Deng’s Marxist-revisionist “neoliberal” reforms lifted more than half a billion people out of extreme poverty, albeit unevenly and at the cost of greater inequality. That was about one-twelfth of the entire world population in 2000. With this development, China halved the global level of extreme poverty. The bulk of the poverty reduction in China came from rural areas.

This achievement is unprecedented in human experience. If China’s extension of markets is neoliberalism, then neoliberalism is the most beneficial economic policy in history.

Vladimir Lenin and Josip Tito as neoliberals

But earlier contenders for the title of “the first neoliberals” can be found. In her book on Markets in the Name of Socialism: The Left-Wing Origins of Neoliberalism, the sociologist Johanna Bockman found roots of neoliberalism in the experiments in so-called “market socialism” in Josip Tito’s Yugoslavia from the 1950s and in Hungary from the 1960s.

There is no stopping this neoliberal treachery – infiltrating socialism as well as capitalism!

Josip Tito

Adopting the methodology of Harvey and Bockman, I would like to nominate Vladimir Ilyich Lenin as the first neoliberal, for his betrayal of socialist central planning and his introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in Soviet Russia in 1921. In this admitted “retreat” from socialism, Lenin re-introduced markets and profit-seeking private firms.

Crucially, in support of this nomination, there is evidence that Deng’s post-1978 reforms drew a strong inspiration from Lenin.

“A brainless synonym for modern capitalism”

Of course, I am being ironic. My point is that, thanks to Harvey and others, neoliberalism as a term has become virtually useless. As Philip Mirowski and Dieter Plehwe put it, neoliberalism for some has become “a brainless synonym for modern capitalism.”

Mirowski also complained that opponents “often bandy about attributions of ‘neoliberalism’ as a portmanteau term of abuse”. But Mirowski did not drop the term.

Geoffrey Hodgson & Philip Mirowski

In his superb history of the Mont Pèlerin Society, Angus Burgin commented critically on the term neoliberalism:

“It is extremely difficult to treat in a sophisticated manner a concept that cannot be firmly identified or defined.”

The word is no longer sound currency. Bad usage has driven out the good. It has become a swear-word rather than a scientific term.

Neoliberalism as a ruling class strategy

Part of the impetus behind the excessive and ultimately destructive use of the word neoliberal is the Marxist belief, expressed by David Harvey among others, that neoliberalism is a strategy serving the interests of the capitalist class.

Following the post-war settlement of 1945-1970, which conceded greater power and shares of income to organized labour, rising neoliberalism allegedly rescued the capitalist class.

Their evidence is that in several major countries from the 1970s, trade unionism declined in strength and the shares of national incomes going to the top five per cent increased.

Second, in several countries, including most dramatically in China, standards of living have increased, even for the lower income deciles. While for many people in the US, real wages have stagnated, this has not been the case in several other countries, particularly prior to the 2008 crash.

Third, the argument may exaggerate the degree to which the capitalist class is united, in terms of their real interests or of their perceptions of them.

Fourth, it is questionable that capitalist interests are best served by declines in real wages, given the powerful Keynesian argument that capitalist prosperity depends on effective demand in the economy as a whole. Higher real wages can increase prosperity across the board, and serve the interests of capitalists and capitalism.

Fifth, there are other, possibility more effective, strategies for countering the power of organized labour and reducing the incomes of many people in favour of the top five per cent. These alternatives include economic nationalism, which can take the extreme form of fascism. Generally these are not free-market, small-state approaches. If they are all labelled neoliberal, and regarded as the grand global strategy of the bourgeoisie, then the analysis becomes dangerously insensitive to the increasingly probable threats of economic nationalism and fascism.

Neoliberalism and the Mont Pèlerin Society

Perhaps the most well-informed and intelligent attempt to give neoliberalism a distinctive meaning is by Philip Mirowski, who associates it, more or less, with the Mont Pèlerin Society.

But the Mont Pèlerin Society changed to a degree, in substance and direction. It began under a different name in the 1930s and was first convened under its current name in 1947. It was then an attempt to convene different kinds of liberals in defence of a liberal market economy, just after the defeat of fascist tyranny, during an expansion of Communist totalitarianism, and while witnessing the rise of statist socialist ideas in Western Europe and elsewhere. Liberalism broadly was on the rocks: it needed its defenders.

As a measure of the relative inclusivity and internal diversity of the Mont Pèlerin Society, consider the testimony of the philosopher Karl Popper, who was a friend of Hayek and a prominent Mont Pèlerin member in the early years. Popper wrote to Hayek in 1947 that his aim was “always to try of a reconciliation of liberals and socialists”.

Michael Polanyi and Wilhelm Röpke

Michael Polanyi – the brother of Karl Polanyi – was a founder member of the Mont Pèlerin Society. He advocated Keynesian macroeconomics in a market economy, alongside a radical redistribution of income and wealth. He rejected a universal reliance on market solutions, seeing it as a mirror image of the socialist panacea of planning and public ownership. He did not mince his words against this “crude Liberalism”:

“For a Liberalism which believes in preserving every evil consequence of free trading, and objects in principle to every sort of State enterprise, is contrary to the very principles of civilization. … The protection given to barbarous anarchy in the illusion of vindicating freedom, as demanded by the doctrine of laissez faire, has been most effective in bringing contempt on the name of freedom …”

Polanyi had drifted away from the Mont Pèlerin Society by 1955, stressing its inadequate solutions to the problem of unemployment and its promotion of a narrow view of liberty as the absence of coercion, neglecting the need to prioritize human self-realization and development.

Michael Polanyi

In its early years, the Mont Pèlerin Society hosted debates on the possible role of the state in promoting welfare, on financial stability, on economic justice, and on the moral limits to markets. Like Polanyi and other early members of the society, Wilhelm Röpke argued that the state was necessary to sustain the institutional infrastructure of a market economy. The state should serve as a rule-maker, enforcer of competition, and provider of basic social security. Röpke’s ideas were highly influential for those laying the foundations of the post war West German economy.

While they received a more sympathy from Hayek, Ludwig Mises regarded Röpke’s views as “outright interventionist”. Mises once became so frustrated with these ongoing arguments in favour of a major role for the state that he stormed out of a Mont Pèlerin Society meeting shouting: “You’re all a bunch of socialists.”

The rise of Milton Friedman

Angus Burgin’s history of the society shows how its early period of relative inclusivity was followed by schisms, departures, and a narrowing of opinion. People like Polanyi and Röpke became inactive. Eventually the primary locus of the Mont Pèlerin Society shifted to the US, with greatly increased corporate funding under the rising intellectual leadership of Milton Friedman.

Milton Friedman

Hence the Mont Pèlerin Society evolved from a broad liberal forum to one focused on promoting a narrow version of liberalism that is more redolent of Herbert Spencer than of Adam Smith, Thomas Paine or John Stuart Mill.

This ultra-individualist liberalism entailed a narrow definition of liberty as the absence of coercion, it relegated the goal of democracy, it neglected economic inequality, it overlooked the limits to markets, it saw very limited grounds for state welfare provision and intervention in financial markets, and it stressed self-interest rather than moral motivation.

Perhaps Friedman was a neoliberal. Perhaps Hayek too. But if we add Lenin, Tito, Deng or Trump to the list, then we are in the realms of absurdity – the term becomes useless.

1 June 2018

This book elaborates on the issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Bockman, Johanna (2011) Markets in the Name of Socialism: The Left-Wing Origins of Neoliberalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

Burgin, Angus (2012) The Great Persuasion: Reinventing Free Markets since the Depression (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press). See esp. pp. 57, 80-86, 116, 121.

Cahill, Damien and Konings, Martijn (2017) Neoliberalism (Cambridge UK and Medford MA: Polity Press). See esp. pp. 144-5.

Harvey, David (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press). See esp. pp. 1-3, 120-22.

Jacobs, Struan and Mullins, Phil (2016) ‘Friedrich Hayek and Michael Polanyi in Correspondence’, History of European Ideas, 42(1), pp. 107-30.

Mirowski, Philip (2013) Never Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: How Neoliberalism Survived the Financial Meltdown (London and New York: Verso). See esp. pp. 29, 71.

Mirowski, Philip and Plehwe, Dieter (eds) (2009) The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press). See esp. p. xvii.

Pantsov, Alexander and Levine, Steven I. (2015) Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press). See esp. p. 373.

Polanyi, Michael (1940) The Contempt of Freedom: The Russian Experiment and After (London: Watts). See esp. pp. 35 ff., 57-58.

Ravallion, Martin, and Shaohua Chen (2005) ‘China’s (Uneven) Progress against Poverty’, Journal of Development Economics, 82(1), pp. 1-42.

Posted in Donald Trump, Left politics, Lenin, Liberalism, Markets, Michael Polanyi, Neoliberalism, Philip Mirowski, Private enterprise, Right politics, Soviet Union, Tony Blair, Uncategorized

February 18th, 2018 by geoffhodgson1946

But it does not deserve to be there

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Despite the disastrous record of self-described “socialist” regimes, socialism (whatever it means) is remarkably popular.

According to a 2017 survey of American adults, 37 per cent preferred (what they described as) socialism to capitalism. Among millennials (meaning those reaching adulthood in the early twenty-first century), 44 per cent preferred socialism over capitalism. This survey broadly confirmed previous American polls from about 2015, which showed a surge of support for socialism, especially among younger people.

According to a 2017 survey of American adults, 37 per cent preferred (what they described as) socialism to capitalism. Among millennials (meaning those reaching adulthood in the early twenty-first century), 44 per cent preferred socialism over capitalism. This survey broadly confirmed previous American polls from about 2015, which showed a surge of support for socialism, especially among younger people.

Polling in the UK found that 39 per cent of adults have an unfavourable view of capitalism, while 33 per cent were favourable. Also in the UK, 36 per cent viewed socialism favourably, compared to 32 per cent negatively. Germans were reported as even more positive about socialism, with 45 per cent being favourable and 26 per cent unfavourable.

These polling figures are remarkable, especially when we take into account that regimes describing themselves as socialist led to over 90 million deaths in the twentieth century. Socialism has captured the ethical high ground, despite the poor record of socialist regimes in terms of human rights.

Somehow today’s socialists evade this legacy. They argue that these regimes were not really socialist. Or they were corrupted by bad leaders. Or they suffered largely because of antagonism from the capitalist West. All these arguments assume that a humane socialism is feasible and that there are not congenital flaws in socialism that lead it to dictatorship.

Love, care and cooperation

Socialism raises the moral flag because it claims to be the creed of love, care and cooperation. By contrast, it is argued, capitalism and markets encourage selfishness and greed.

Socialism raises the moral flag because it claims to be the creed of love, care and cooperation. By contrast, it is argued, capitalism and markets encourage selfishness and greed.

Socialists point to defenders of capitalism such as Ayn Rand, who like the fictional Gordon Gekko in the 1987 movie Wall Street, promoted the view that that greed is good and altruism is evil.

Mainstream Economists are tainted too: they often favour markets and assume individual self-interest as an axiom. Socialism will subdue markets, private profits and other spurs to greed, and through common ownership create a system that encourages people to cooperate together and act unselfishly.

So the argument goes. But the evidence tells a different story. The socialists, the “greed is good” defenders of capitalism, and believers in our total selfishness are all wrong.

So the argument goes. But the evidence tells a different story. The socialists, the “greed is good” defenders of capitalism, and believers in our total selfishness are all wrong.

Theory and evidence, from Darwin onwards, show that evolution has provided humans with a mixture of selfish, cooperative and moral capacities, which can be stunted or developed according to different cultural and institutional settings.

There is also strong evidence that market or trading relationships can enhance sentiments of fairness and reciprocity. The notion that markets always make people greedy, selfish and amoral has been refuted. The moral high ground claimed by socialism is challenged not simply by the misdeeds of socialist dictators, but also by extensive evidence about human nature and how it is affected by markets or other institutional circumstances.

Small-scale societies have relied on sentiments of cooperation and moral solidarity that have evolved within groups over millions of years. Solidarity within tribes or bands helped them survive in competition over resources with their rivals. But unfortunately evolution has not disposed us to be nice to outsiders.

The modern world has built up citizen loyalty to nation states, but the downsides have been hostility to foreigners and belligerent nationalism. In the modern world, institutions are needed to encourage mutual understanding and reciprocity on a global scale.

Thomas Paine

One of these institutions is the market. There is impressive evidence that, on balance, international free trade can reduce the risks of war between nations. In larger-scale systems, despite market competition, trade can build bonds and reduce conflict.

While the complete commercialisation of family and community life could undermine trust and altruism, wider trade on a larger scale increases mutual interdependence. As Thomas Paine, Richard Cobden, John Hobson and several others argued, markets can help to build solidarity within and between nations.

Socialism as “obvious”

Yet, despite evidence to the contrary, socialism still clings to the high moral ground. For Jeremy Corbyn and many others, socialism is an “obvious” response, where caring for one another supersedes the greed and profit-seeking that is always fostered by capitalism. Little further detailed evidence is deemed necessary.

If socialism is “obvious”, then how do we explain the failure of other intelligent people to get on board? If they are not stupid, then they must be acting out of personal malice or greed. They must have sold out their principles in some way. Or they are just plain nasty.

When socialism is seen as “obvious”, its opponents are regarded as stupid or evil. Because the solution is “obvious” there can be no doubt. There is no need to look at evidence, to experiment, to seek wise counsel, or to listen to critics. Those that deny the obvious are deluded, corrupt, or in the pay of those that gain from the existing system.

Hence the claim that “socialism is obvious” encourages a remarkable intolerance of those that take a different view.

Modern economies are highly complex, and to pose any system or solution as “obvious” is a dangerous populist naivety. Precisely because something called socialism has now become popular, we are entitled to ask more precisely what it means.

Socialists compare an imaginary “obvious” world with the real world, with all its poverty, inequality and other problems. They simply assume that their imaginary world of love and cooperation will work. They assume that much can be decided democratically, ignoring the fact that it is impossible to make more than a small fraction of day-to-day decisions democratic. They ignore the problems of incentivizing work and innovation, and of ensuring functional autonomy without private property. All these problems became apparent in real-world socialist experiments in the past.

Socialism and dictatorship

A major problem with large-scale socialism is that a large concentration of political and economic power in the hands of the state undermines the economic foundations of countervailing power and empowers totalitarian forces and outcomes. These problems are illustrated by developments in Russia, China and Venezuela.

Such a centralization of economic power requires and promotes a strong executive, unburdened by checks and balances. When this concentration of economic power is achieved, it reinforces political centralization in the absence of countervailing interests and powers.

Such a centralization of economic power requires and promotes a strong executive, unburdened by checks and balances. When this concentration of economic power is achieved, it reinforces political centralization in the absence of countervailing interests and powers.

The argument that “good” leaders will avoid these pitfalls is spurious. Without checks and balances there are strong temptations to cut constitutional corners. Eventually a “good” leader will be succeeded by someone worse, who will have less scruples about abusing executive power.

The conclusion is that democracy and human rights require countervailing power and a market economy with a much smaller public sector. Countervailing interest groups, with their own access to resources and an ability to check or influence the state, are necessary to prevent democratic abuses and over-centralization.

Ignoring this powerful argument, in the face of extensive historical evidence in its support, is morally reprehensible. It betokens a moral irresponsibility in the light of ample evidence to the contrary. The socialist tenure of the moral high ground is illegitimate.

Conclusion

Instead, the moral high ground should be conceded to those who understand that:

– modern economic systems are highly complex and cannot be largely planned from the centre

– genuine autonomy requires rights to private ownership

– the existence of democracy and the protection of human rights require countervailing politico-economic power

– mixed economies have the best economic performance

– a welfare state is necessary to protect the poor and needy

– instead of chasing unicorns, we should follow the example of those capitalist countries that have the lowest levels of inequality.

18 February 2018

Published January 2018

Bibliography

Boehm, Christopher (2012) Moral Origins: The Evolution of Virtue, Altruism and Shame (New York: Basic Books).

Bowles, Samuel and Gintis, Herbert (2011) A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and its Evolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Courtois, Stéphane, Werth, Nicolas, Panné, Jean-Louis, Packowski, Andrzej, Bartošek, and Margolin, Jean-Louis (1999) The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press).

Darwin, Charles R. (1871) The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 2 vols (London: Murray and New York: Hill).

De Waal, Frans B. M. (2006) Primates and Philosophers: How Morality Evolved (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Haidt, Jonathan (2012) The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion (London: Penguin).

Henrich, Joseph, Boyd, Robert, Bowles, Samuel, Camerer, Colin, Fehr, Ernst, Gintis, Herbert and McElreath, Richard (2001) ‘In Search of Homo Economicus: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-Scale Societies’, American Economic Review (Papers and Proceedings), 91(2), May, pp. 73-84.

Henrich, Joseph, Boyd, Robert, Bowles, Samuel, Camerer, Colin, Fehr, Ernst, and Gintis, Herbert (2004) Foundations of Human Sociality: Economic Experiments and Ethnographic Evidence from Fifteen Small-Scale Societies (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press).

Henrich, Joseph, Jean Ensminger, Richard McElreath, Abigail Barr, Clark Barrett, Alexander Bolyanatz, Juan Camilo Cardenas, Michael Gurven, Edwins Gwako, Natalie Henrich, Carolyn Lesorogol, Frank Marlowe, David Tracer, and John Ziker, (2010) ‘Markets, Religion, Community Size, and the Evolution of Fairness and Punishment’, Science, 327 (5972), pp. 1480-84.

Hirschman, Albert O. (1982) ‘Rival Interpretations of Market Society: Civilizing, Destructive, or Feeble?’ Journal of Economic Literature, 20(4), December, pp. 1463-84.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2013) From Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities: An Evolutionary Economics without Homo Economicus (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

McDonald, Patrick J. (2004) ‘Peace through Trade or Free Trade?’ Journal of Conflict Resolution, 48(4), August, pp. 211-22.

Sober, Elliott and Wilson, David Sloan (1998) Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press).

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Labour Party, Left politics, Markets, Nationalization, Neoliberalism, Private enterprise, Property, Socialism, Soviet Union, Venezuela

January 11th, 2018 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Although education is not a public good, there are good reasons why the state should support education services.

As leader of the UK Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn has opined that “education is a public good” and drawn the conclusion that it should all be provided by government and funded by taxation.

All three leaders of the UK Green Party since 2012 – Nathalie Bennett, Caroline Lucas and Jonathan Bartley – have repeated the phrase “education is a public good”. They too implied that all education should be free of charge to the user and paid for out of taxation.

Jeremy Corbyn and Caroline Lucas

Similarly, Shakira Martin, who was elected President of the UK National Union of Students in 2017, remarked: “Education is a public good and should be paid for through taxation.” These influential organizations are led by people who have not learned the lessons of Econ 101.

In addition, this inaccurate rendition of the meaning of public good is common among journalists, who also have a moral responsibility to use terms accurately.

What is a public good?

The economist and Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson established the concept of a public good in an academic paper in 1954, although some of the basic ideas involved had been formulated previously by others.

John Stuart Mill, for example, had argued in his Principles of Political Economy that lighthouses should be built and financed by governments, because their widespread benefits could not readily be financed by passing ships, and no individual had the pecuniary incentive to construct them.

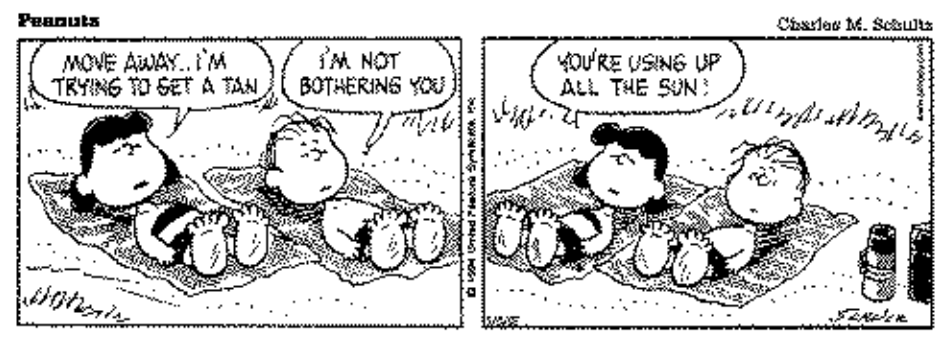

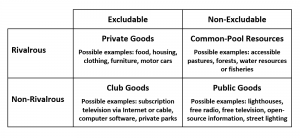

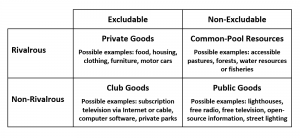

The established technical definition of a public good is a good or service that is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. Non-rivalrous means that its use or consumption by any actor does not significantly reduce the amount available for others.

Non-Rivalrous Consumption

Non-excludable means that potential users cannot practically be excluded from the use of the good or service. This definition can be confirmed by reading any reputable economics textbook.

Consider the example of street lighting. If a town council uses local tax revenues to set up and maintain lighting on its streets, then there are widespread benefits for everyone. But it is not possible to charge people individually, according to whether they benefit from the illumination.

So when elections to the town council occur, self-interested citizens will vote for candidates proposing lower taxes, assuming that they will benefit anyway from any public good provision. Why pay more taxes when the lighting is free at the point of use? Self-interested consumers will try to hitch a free-ride. The outcome is that the street lighting will be underfunded, while everyone would prefer streets that are well-lit.

Free Riders

Samuelson’s argument was popularized by John Kenneth Galbraith in his 1958 book The Affluent Society. Therein Galbraith argued that vital public goods would be under-provided in a market system: there could be the coexistence of “private opulence and public squalor”. The combined efforts of a revered mainstream economic theoretician and of an astute and inventive populariser of economic wisdom helped to pave the way for a wave of interventionist policies in the US and other developed economies.

Do public goods necessitate public provision?

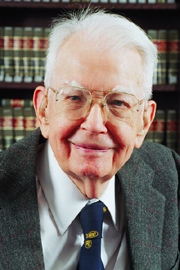

After this action came the reaction. In a 1974 article Ronald Coase (another Nobel Laureate) argued that many early lighthouses in England were privately constructed and financed by tolls at the ports. In fact, an emblematic example of a public good had often been financed privately. Hence “economists should not use the lighthouse as an example of a service which could only be provided by government”.

Ronald Coase

This and other interventions led to a widespread reaction against the Samuelson-Galbraith view that public goods necessarily require public provision or public financing.

It has been pointed out that radio and TV broadcasts and open-source computer software are also public goods. Yet both are often provided by private companies. Private radio and TV broadcasters finance their broadcasts by advertising.

Computer companies sometimes make software readily available to encourage use of their computers, for which the software was designed. The software is given away to help sell the hardware, or there is a charge for support services for software users.

Whether they are desirable or not, in principle there are many possibilities for private provision of public goods. In reality there are numerous cases where the state franchises out the provision of goods or services to private contractors. Such provision could include public goods. In these cases, public financing remains, but provision is private.

The claimed advantages of private franchising would include the introduction of an element of competition between potential franchisees, and the possibilities of efficiency gains through well-focused, relatively autonomous private providers. But here again the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Many public franchising operations have failed to deliver the promised gains. Others have been more successful.

Accordingly, we end up with a pragmatic rather than a doctrinaire conclusion. Economic systems are complex, with varied, interconnected components. Theory simplifies, and does not catch all the interactive effects. Theory has continuously to be appraised in the light of empirical experience. So far it is clear than the existence of a public good does not necessarily imply that it has to be provided by government, just as there is no compelling case that its private provision will also be superior.

Misunderstanding the meaning of a public good

Careful, rational discussion of the issues surrounding vital debates over public and private provision is not simply impeded by the prevalence of opposing ideological extremes. There is also a growing and prominent disrespect for the careful use of the terms that have been established by scholars in this area.

Combinations of sloppiness and ignorance threaten the utility of key terms. They engender ambiguity, degradation and ultimate uselessness. This has already happened with swear-words such as neoliberalism. It is hoped that it does not happen with cheer-words such as public good.

A prominent misunderstanding of “public good”, is that it means “a good that can only, or should only, be provided by government”. But this conflation of public good with public provision is mistaken.

Another, even cruder, misunderstanding is that “public good” means “good for the public”. While anyone who has taken Econ 101 should spot this error, it is nevertheless widespread. Speakers sometimes give their error away when they give relative stress the “good” in the phrase, as if “good” had the meaning of virtuous or worthwhile.

Yet in the correct definition of “public good” the second word takes another commonplace meaning, denoting a possession, or an item of commerce. This second meaning is found in the pledge “with all my worldly goods I thee endow” in the Book of Common Prayer or in “the goods train went through the station”. Bad things, like tobacco, heroin, cocaine, nuclear bombs and personnel mines, are also goods in this sense.

Is education a public good?

First assume that the claims of Corbyn, Lucas and others were true: education is “good for the public” and it should be funded out of taxation, and maybe even provided by a publicly-owned enterprise.

Many additional things are “good for the public”, including clothing, food and housing. By the same logic, these “goods” should all be funded out of general taxation as well, and distributed without further charge to their users. Influential politicians thus suggest that everything that serves basic needs should be financed, and possibly distributed, by the state. The market would simply be left for luxuries. Their logic implies a state-run economy of which Stalin and Mao would be envious.

Second, even if education were a public good (by the Econ 101 definition) then this would not imply that it should be paid for out of taxation. As noted above, free radio and TV broadcasting is generally a public good, but little of it is paid out of taxation, and it would be difficult to make the case that it should be (unless we fancy a totalitarian state that does all the broadcasting and curtails all private radio and TV stations).

Third, while observing the Econ 101 definition of a public good, note that education is generally a rivalrous rather than a non-rivalrous service. Education services require resources, including buildings, infrastructure, equipment and trained teachers. Additional students generally require additional resources. (Although in some cases the marginal cost is low, such as with mass-distributed online courses.) Consequently, education provision is generally rivalrous.

Third, while observing the Econ 101 definition of a public good, note that education is generally a rivalrous rather than a non-rivalrous service. Education services require resources, including buildings, infrastructure, equipment and trained teachers. Additional students generally require additional resources. (Although in some cases the marginal cost is low, such as with mass-distributed online courses.) Consequently, education provision is generally rivalrous.

Fourth, again with an eye on the Econ 101 definition, note that education services are mostly (but not entirely) excludable. Schools and universities can readily prevent other people from attending, while it is much more difficult to prevent any passing mariner from observing the light from a lighthouse.

Technically, by the standard definition, most education services are private goods, because their provision is both excludable and rivalrous. But there is no necessary reason why all private goods should be privately provided. The Econ 101 distinction between public and private goods does not readily or directly correspond with public and private provision respectively.

The parts of an education system that are actually or virtually non-rivalrous, such as massive online courses, are technically club goods. Like radio and TV broadcasting they can be provided publicly or privately.

Positive externalities in education

When students receive their qualifications, they often have advantages over others on the jobs market. Hence they reap benefits. Nevertheless, with education there are strong positive spill-over effects.

Educated people help to raise the levels of public culture and discourse, and can pass on some of their skills to others. Educated people are also vital for a healthy democracy. But none of this undermines the general excludability of education services.

The spill-over effects are important, and relate to the question of public versus private provision. Another word for a spill-over is an externality: this is a cost or benefit that affects someone who did not choose to incur that cost or benefit.

Externalities can be positive or negative. Examples of negative externalities are pollution or congestion caused by motor cars. Because a driver will suffer only a fraction of the overall pollution and congestion costs of making a car journey, negative externalities impose costs on others without penalty for the car user. By standard assumptions, unless compensatory measures are taken, car use will be excessive and suboptimal.

Arthur Pigou

The theory of externalities was developed by Arthur Pigou, who argued that in the presence of negative externalities some public authority should intervene to impose taxes or subsidize superior alternatives. By such measures, motor car traffic could be reduced and pollution reduced. Inversely, services such as education with positive externalities should receive subsidies or be provided free, to encourage more extensive participation in these activities.

In a famous 1960 paper, Coase dramatically changed the terms of debate with his argument that if transaction costs were zero, then all the extra costs or benefits could be subject to contractual arrangements and the externalities would disappear. For example, if the owner of every dwelling near a road had property rights in the surrounding segment of the atmosphere, then the driver of a passing and polluting car could be sued for degradation of that property. The pollution externality would be internalized.

Coase’s intention was to underline the implications of transaction costs: the existence of externalities is dependent on positive transaction costs. Coase accepted that in many cases it would be impossible to avoid the transaction burden. For example, enforcing rights in the surrounding atmosphere to curb pollution may be too expensive.

Many pro-market zealots ignored or underestimated the transaction-cost aspect of Coase’s argument. Instead, their foremost claim was that Coase had undermined the case of public intervention based on externalities.

Consider the positive externalities of education. It would be impossible or socially destructive for every educated person to charge a fee to participants in an intellectual dinner conversation, or to invoice the government for making a well-informed choice when casting his or her vote in the ballot box. The internalization of these positive externalities by such means is impossible or undesirable.

The issue of missing markets is relevant here, as I discuss in my book Conceptualizing Capitalism. There are missing markets for future employment because to introduce such complete markets would be tantamount to slavery. The prohibition of slavery means that we cannot have complete futures markets for labour. This means not simply the existence of transaction costs but the enforced absence of transactions, which would be equivalent to making the transaction costs infinite.

The issue of missing markets is relevant here, as I discuss in my book Conceptualizing Capitalism. There are missing markets for future employment because to introduce such complete markets would be tantamount to slavery. The prohibition of slavery means that we cannot have complete futures markets for labour. This means not simply the existence of transaction costs but the enforced absence of transactions, which would be equivalent to making the transaction costs infinite.

Consequently, because of these missing markets, education and training will be undersupplied through markets under capitalism. There is a rationale for some kind of public intervention. Of course, government intervention has its problems too. We must experiment, and compare real-world cases, not idealized models.

Mixtures of public and private provision

There are mixtures of public and private provision of education in most countries. The majority of schools in most countries are run by local government. At the other extreme, most on-the-job training is done by private companies.

The US has a mixture of private and state universities, although both types receive substantial public funds. In the UK most universities receive public money for teaching and research, and in return they are obliged to conform to a myriad of government regulations. They also receive student fees and research grants from the private sector.

Technically all UK universities are private (corporate) entities: they have a legal status equivalent to charities (which are also not-for-profit private corporations). By contrast, in several major countries in Continental Europe and elsewhere, most universities are integrated into the state machinery and all their employees are civil servants. This is not the case in the US or the UK. This international diversity of models provides the opportunity to compare different systems and determine what works best, taking account of the different contexts in which they operate.

J’accuse: abetting Trumpism

This growing disrespect for science and expertise is moving democracies toward an extremely dangerous place, where the general public have increasing difficulty segregating lies from truth. This danger could be called Trumpism.

I do not put Jeremy Corbyn or Caroline Lucas in the same box as Trump. Far from it. For example, they share none of his obnoxious racism and sexism. But Corbyn and Lucas are disrespecting experts and ignoring bits of science nevertheless.