May 5th, 2018 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

Karl Marx was born on 5 May 1818. He was one of the greatest social scientists in human history. The intellectual structure of his thought has affected our understanding of history, of economic development and of political power. All modern scholars of significance have to define their position in relation to Marx’s monumental achievement.

Many of Marx’s predictions were wrong. He was mistaken, for example, about the general deskilling of the working class. On the contrary, although many remain unskilled, average skill levels have increased. Furthermore, although many remain desperately poor, the average standard of living of the working class has vastly increased since his time.

On the other hand, some of Marx’s predictions have been vindicated. He characterized the nature of the capitalist system more acutely than any of his predecessors and he predicted its spread over the entire world. He saw capitalism a dynamic system that broke down archaic institutions and barriers to trade.

Marx also focused on the generation of inequality under capitalism, which has increased and is recognized as a serious problem.

Marx got some forecasts wrong and some right. Prediction is far from everything in social science. What towers above all is his contribution to our understanding of the inner dynamics of capitalism. With all its shortcomings and theoretical flaws, it remains a huge achievement.

Was Marx the author of the Marxist tragedy?

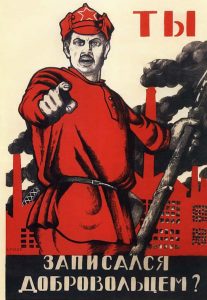

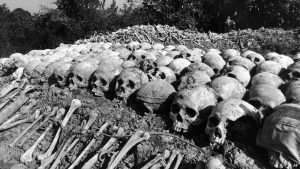

Let us turn from Marx the social scientist to Marx the politician. Remarkably, from 1917 to the present day, a number of regimes have been set up by revolutionary activists who have claimed to be Marxists. All of these turned sour: these totalitarian regimes led to millions of deaths. Estimates vary. 90 million is on the conservative side, with about 65 million in Mao’s China alone.

Marxism has various ideological immune systems to deal with these brutal facts. One gambit is to blame it on the hostile interventions of foreign powers. But it is implausible that these alone are responsible for the outcomes. No foreign intervention prompted Mao’s Great Leap Forward of his Cultural Revolution, for example, which together led to about 40 million deaths.

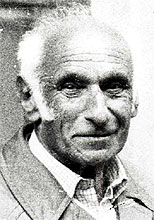

Leon Trotsky

Another argument – due to Leon Trotsky – is to blame it on the creation by tyrannical leaders such as Stalin of a bureaucratic caste that denied the working class any democratic power. But this implausibly assumes that a huge nationwide bureaucracy can somehow be run on the basis of meaningful votes on every important decision. No-one with any practical experience of a large organization would entertain such a fantasy.

A more colourful recent excuse is due to Yanis Varoufakis, the influential Greek academic and politician. He argued that the Marxist texts were too powerful. As a result they attracted devious opportunists who rode the Marxist rhetoric for “their own advantage.”

The problem, it seems, was that Karl Marx and Frederick Engels were too powerful with their prose. If only they had written more turgid texts – then millions would have been saved from the famines and the Gulags.

Seriously, though, the greater problem is not the power of the language, but what it says and what it empowers and enables. Marxism creates a sense of historical destiny, where the creation of socialism is a seemingly obvious solution to the ills of the world, which will defied only by the rich, whose resistance must be crushed.

Marx bears some responsibility for the murdered millions

At least two major aspects of Marx’s thought removed protections of human rights and paved the way for brutal totalitarianism.

The first was his doctrine of class struggle. Analytically, this may have some value and it is subject to academic debate. But it was also a normative doctrine, about the working class seizing power and ending the rule of the capitalists.

Marx and Engels argued that the current aims and desires of the proletariat were less important than its historical destiny to abolish capitalism and become the ruling class. They wrote:

This is the first totalitarian impulse. Marxist revolutionaries are deemed to know better what is in the interests of the working class than the working class itself. Democracy becomes an impediment to the realization of those true interests, about which the masses are not fully aware.

The normative doctrine of class struggle has another outcome. It means that the rights of one social class are privileged over another. Universal individual rights are no more. As Engels put it, legal and individual rights are “nothing more than the idealized kingdom of the bourgeoisie.”

Their normative arguments in favour of socialism are not based on any alleged rights. Instead, socialism is seen as historic destiny. Marx tried to show that crises within capitalism are recurrent and inevitable, and that capitalism digs its own grave by enlarging and empowering the working class.

The consequence of this class deprivation of human rights was enshrined in law under Marxist-socialist regimes. The 1918 Constitution of the young Soviet regime distinguished between the rights of the workers and the rights of others. The Soviet state also announced that it

The consequence of this class deprivation of human rights was enshrined in law under Marxist-socialist regimes. The 1918 Constitution of the young Soviet regime distinguished between the rights of the workers and the rights of others. The Soviet state also announced that it

A major problem here was that the criteria used to decide what was detrimental were unspecified, opening the door to arbitrary repression by the authorities. This is exactly what happened.

A regime that denies rights to some, especially with malleable criteria concerning who is denied those rights, ends up denying rights to everyone. These are the consequences of Marx’s “dictatorship of the proletariat”.

A full concentration of economic power leads to totalitarianism

A second aspect of Marx’s thought that promoted totalitarianism concerns the economy.

But as subsequent experiences from Russia to Venezuela illustrate, such a massive concentration of economic power requires for its enforcement, and sustains as an outcome, a massive concentration of political power that is intolerant of democracy. The good intentions or democratic inclinations of leaders are not enough. Those most hungry for power, and least affected by moral qualms in exercising it, will eventually rise to the top.

There is a widespread opinion among non-Marxist social scientists (including Barrington Moore, Douglass North and Francis Fukuyama) that democracy requires countervailing political and economic power to have a chance of survival. In Marxist terms, if the economic “base” determines the “superstructure”, then a pluralist polity requires a pluralist (or mixed) economy, not one that is overshadowed by a massive state.

A complete concentration of political and economic power in the hands of the state, which Marx and Engels advocated with enthusiasm as well as eloquence, always requires and enables a despotic political regime. There are no exceptions.

Leszek Kolakowski

Over forty years ago, Leszek Kolakowski was an Eastern European dissident and a perceptive critic of Marxism. He wrote:

“My suspicion is that this was both Marx’s anticipation of perfect unity of mankind and his mythology of the historically privileged proletarian consciousness which were responsible for his theory being eventually turned into an ideology of the totalitarian movement: not because he conceived of it in such terms, but because its basic values could hardly be materialized otherwise.”

Kolakowski was right. Many have still to learn the tragic lessons of Marxist failure in practice, as well as of its partial but flawed analytical success.

Critics will say that giving Marx some blame for the atrocities of the twentieth century is like trying to blame Jesus for the atrocities of the Spanish Inquisition. They are wrong, Jesus never advocated class war or a concentration of economic power in the hands of the state, both of which create the conditions for tyranny.

5 May 2018

Minor edits – 6 May 2018

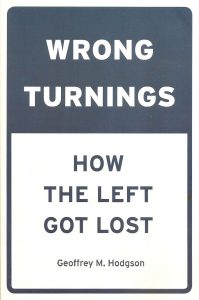

This book elaborates on the issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Courtois, Stéphane, Werth, Nicolas, Panné, Jean-Louis, Packowski, Andrzej, Bartošek, and Margolin, Jean-Louis (1999) The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press).

Fukuyama, Francis (2011) The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution (London and New York: Profile Books and Farrar, Straus and Giroux).

Kolakowski, Leszek (1977) ‘Marxist Roots of Stalinism’, in Robert C. Tucker (ed.) (1977) Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation (New York: Norton), pp. 283-98.

Moore, Barrington, Jr (1966) Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World (London: Allen Lane).

North, Douglass C., Wallis, John Joseph and Weingast, Barry R. (2009) Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press).

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, Karl Marx, Labour Party, Left politics, Lenin, Leszek Kolakowski, Liberalism, Mao Zedong, Markets, Nationalization, Politics, Private enterprise, Property, Robert Owen, Socialism, Uncategorized

September 20th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

I was born in 1946. I lived in a council house until I was 16. My family were Labour. My privilege was not money, but that my parents and grandparents all valued education and culture. But none of them obtained a university degree, because they were less accessible at the time.

Harold Wilson

I became involved in the Labour Party in 1964 and then saw myself as a Tribune socialist following the steps of great radicals such as Michael Foot. After welcoming Harold Wilson’s election victory in 1964, I became critical of the new Prime Minister because of his nominal support for the US in the Vietnam War.

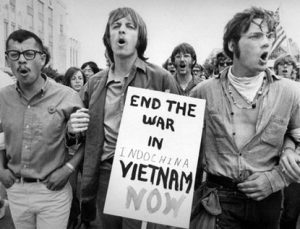

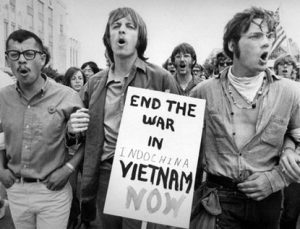

Vietnam and Marxism

For my baby-boom generation, the Vietnam War was a great generator of radicalism. Like many of my university friends, I became a Marxist in 1966. We were drawn into a turbulent and exciting world that combined activism with ideas and debate. I saw myself as a Marxist until about 1980.

I studied mathematics and philosophy from 1965 to 1968 and economics from 1972 to 1974. Both periods were at the University of Manchester. In the intervening years I taught myself Marxist economics. My knowledge of economics became enduringly significant in my political evolution.

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

Marxists dominated the activists on the university campuses. The left was divided and fractious. There were Soviet Bloc loyalists in the Communist Party of Great Britain. There were lovers of Mao Zedong and several rival Trotskyist sects. I could not bring myself to support any totalitarian regime – East or West – so I joined the forerunner of what is now the Socialist Workers’ Party, which saw everything existing as “capitalist”.

My departure from the SWP came in 1971 when they expelled a dissident faction with which I sympathised. (That critical faction eventually became the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty, of Momentum fame in the Corbyn Era.)

I flirted briefly with the International Marxist Group, which included glamorous figures such as Tariq Ali, and Robin Blackburn of the New Left Review. The IMG was stronger in its support for the women’s movement and for gay rights.

After a few years among the sects I could see that something was wrong. These groups were aiming to help create a much better society, but they were generally dogmatic and intolerant. Some were ruthless, pugnacious and fanatical. I did not want to see any social system facilitated or run by these people.

But on the other hand I then accepted the Marxist view that capitalism was exploitative and frequently led to oppression and war. The evidence of this was seemingly before our eyes.

Re-joining Labour and changing strategy

After Labour’s electoral defeat in 1970, there was a strong and growing left in the Labour Party and that seemed the best hope for socialists. Against the advice of Ralph Miliband (whom I knew personally) and others, I re-joined Labour in 1974.

In 1975 I published a pamphlet entitled Trotsky and Fatalistic Marxism. This tried to explain the fanaticism and intolerance of many Marxists in terms of their belief in the imminent decay and collapse of capitalist democracies. Trotskyists had failed to appreciate the enormous expansion and dynamism of capitalism after 1945. Their explanations of the survival of capitalism were weak.

Published in 1977, a longer work entitled Socialism and Parliamentary Democracy elaborated more of my thinking. Marxist-Leninists believed that parliament and the capitalist state should be “smashed”. Influenced by Max Weber and others, I argued that in modern democracies, government drew their perceived legitimacy from parliamentary elections. If socialism became a majority view, then socialists could and should gain a majority in parliament.

In the book I criticised the 1968 revolutionary movement in France for boycotting the elections called by President Charles de Gaulle in that year. Victory in the elections gave de Gaulle legitimacy. The huge movement of students and workers was crushed.

Paris – May 1968

As I had anticipated, my heresies were dismissed out of hand by the far left sects. But the book proved to be rather influential in the UK and internationally. It received a strongly sympathetic hearing on the Labour left. It was translated into Italian, Japanese, Spanish and Turkish. It persuaded a leading member of the violent Basque separatist group ETA to abandon terrorism.

I don’t know if he read my book, but Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the leader of the revolutionary movement in France in May 1968, later argued that it had been a mistake to boycott the French parliamentary elections.

Labour had been reconciled to the parliamentary road to socialism since its formation. The sects argued that it wouldn’t work. My response was that insurrection would not work either. In democracies we needed a combination of parliamentary and extra-parliamentary action.

Questioning ends as well as means

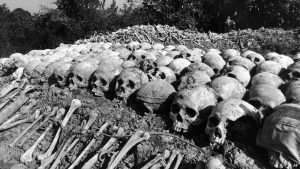

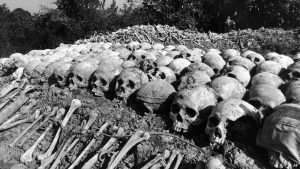

The killing fields in Cambodia affected me deeply. After seizing power in 1975 the Khmer Rouge forced everyone into the countryside and obliterated about two million people – a quarter of the Cambodian population – in the pursuit of their communist utopia.

I could not dismiss this as an aberration. After all, the Khmer Rouge aims, which included the abolition of money, private property and markets, were central to the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels.

Khmer Rouge Killing Fields

The far left were able to publish papers and debate ideas because they lived in a democracy that tolerated freedom of expression. But the ideas and actions of the sects, if they gained influence or power, would curtail these very liberties upon which they had depended.

Crucially, I was not naïve enough to believe that freedom and political pluralism could be guaranteed simply by the goodwill of a more enlightened Marxist leadership, who valued these things more than the Khmer Rouge. Good intentions were not enough.

I had retained a good lesson from Marxism. Effective ideas and practices draw their strength from agglomerations of power sustained by the structures of the politico-economic system. Hence a genuinely pluralist and tolerant political sphere depended on pluralism and decentralisation in the economic domain. A pluralist polity requires a pluralist economy.

Beatrice & Sidney Webb

Prominent Labour thinkers such as Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and G. D. H. Cole had all argued for a decentralised socialist system. But they still sought the abolition of private property and markets. The state would ultimately own everything. So what institutional, legal or other politico-economic forces could stop it retrieving all delegated powers to the centre, when deemed required, or when goodwill wore thin?

Any viable socialism always needs markets

I came to the view that genuine and lasting decentralisation would depend on the existence of organisations with some genuine autonomy and legal independence, providing powers to own property and trade with other organisations. Any viable socialism would always need markets – it was not simply a matter of tolerating or compromising with them.

This crucial transition of my thinking occurred between 1977 and 1980. I cannot recall the detailed influences. But I am sure that the initial impetus did not come from Ludwig von Mises or Friedrich Hayek. I did not delve deeply into their works until the early 1980s.

János Kornai

There had been several socialist proposals to nationalise the sector producing capital goods but retain competition and markets for consumer goods. I was more attracted by the Hungarian economist János Kornai’s more sophisticated proposal (originally published in 1965) to use a dynamic combination of markets and planning, where planning provided strategic impetus, and markets signalled information and gave scope for innovation and planning adjustment.

Over the new year of 1979-1980 I went on a short tourist group visit to the Soviet Union. Some of my companions were dewy-eyed admirers of the system, but I was prepared for its flaws, including the ubiquitous black markets and corruption.

I had been given the address in Moscow of an Englishman married to a Russian. As a former Communist, he explained in detail in his apartment how and why his views had quickly changed: “I challenge any supporter of the Soviet Union to live here just for six months.”

Alec Nove

When Alec Nove published a classic article on feasible socialism in New Left Review in early 1980 I was ready for it. Nove also argued that markets were essential to any viable socialism. He realised that he was attacking deeply-ingrained orthodoxy on the left.

(Later I had the pleasure of meeting both Kornai and Nove several times. Nove died in 1994 but Kornai is still alive. I am delighted to be invited as a keynote speaker at a conference in his honour in Budapest in 2018.)

Labouring as a revisionist

Any acceptance of markets was an anathema to followers of both Karl Marx and Tony Benn. Benn distanced himself from those who supported the persistence of markets.

But I found common ground with Benn and others over what was called “the alternative economic strategy”. I outlined my positive views on this in a pamphlet entitled Socialist Economic Strategy in 1979. It was published by Independent Labour Publications.

Independent Labour Publications was the residue of the old Independent Labour Party, which had played a central role in Labour history from the 1890s to the 1940s. The Independent Labour Party split from the Labour Party in 1931. But in 1975 it formally dissolved as a party and rejoined Labour as Independent Labour Publications.

I was involved in this organisation briefly. Despite outward appearances they turned out to be another sect, lacking any vision of a workable socialism. They too were uneasy about my revisionism. Although my Socialist Economic Strategy was a bestseller by their standards, they refused to reprint it. We parted company in 1981.

Geoff Hodgson, Jean Shepherd & John Maguire in 1979

In 1979 I was the unsuccessful Labour Parliamentary Candidate for Manchester Withington. The seat became Labour in 1987.

I met Benn a few times and supported him in the 1981 deputy leadership election. This alignment was marked in my book Labour at the Crossroads, published in that year. Therein I again supported the alternative economic strategy. But against Benn himself, I argued in that book that in some sectors of the economy “there is no substitute for competition and a market” (p. 206).

(In his important book on The Labour Party’s Political Thought, Geoffrey Foote quotes me (pp. 320, 347) as a “Bennite”. But because of my explicit acceptance of markets, I was unrepresentative of the Bennite stream of thought.)

Subsequently my opinion of Benn shifted. He was a magnificent speaker, but his writings on socialism are vague and unclear. His use of history is unscholarly and cavalier. He was not a well-read intellectual like Michael Foot.

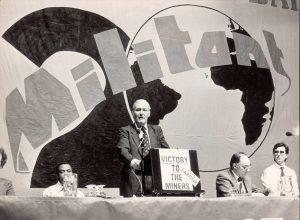

Tony Benn at a Militant meeting

While Benn’s “alternative economic strategy” accepted markets and a private sector for the present, it seemed to me that he wanted to move eventually toward a socialist economy without any markets at all. It was no accident that Benn and his followers defended the Trotskyist sect Militant when they were pushed out of the party from 1985 to 1992.

In 1984 I published my book on The Democratic Economy, where I set out my view on the importance and complementarity of both markets and planning. My argument was framed in socialist language but therein I distanced myself from Marxism. The book received a critical response from many on both the soft and hard left.

The Labour Coordinating Committee

Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979. One of Thatcher’s most popular policies was to promote the sale of council-owned housing to the tenants. Labour had opposed this policy. The disastrous 1983 defeat of Labour on a Bennite manifesto prompted a rethink, on this and several other issues.

For some of us, this rethink amounted to more than expedient doctrinal trimming. Encouraging home ownership was really a good idea: why should all property be owned by the rich? But while supporting home ownership, we argued that the government should also build more social housing and enlarge the stock available for rent by low-income families.

But these ideas met stiff resistance in the Labour Party ranks, and not simply from Trotskyist entryists such as Militant. The resistance from Benn and his supporters was substantial and even more enduring. It was clear that old-fashioned socialist ideas still had a tenacious appeal among Labour’s membership.

The Labour Coordinating Committee (LCC) became one of the primary modernising forces within Labour. Its leadership included Hilary Benn, Cherie Blair, Mike Gapes, Peter Hain, Harriet Harman, Kate Hoey (the Brexiteer) and others of enduring fame. I was elected to the LCC executive committee. We worked closely with the new leader Neil Kinnock, and with members of his shadow cabinet, including Robin Cook.

Changing Clause Four

I have detailed elsewhere my LCC attempt to bring about discussion to change Labour’s Clause Four. The version that had been in place since 1918 called for the “common ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange”. This provided for no exception: all production would be in common ownership and there would be no private sector.

Although some Labour Party thinkers began to entertain the possibility of some private enterprise, many party members remained resolutely in support of widespread common ownership.

Against my efforts, the 1983 AGM of the Labour Coordinating Committee defeated the proposal that Clause Four should be rewritten. This was out of fear of antagonising the Benn wing. Instead, the LCC resolved that Clause Four should be “clarified”.

But a resolution on long-term aims, which I had helped to draft, was passed by a large majority. The resolution called for the Labour Party to draft a new statement of aims, upholding “that socialism involves extended democracy and real equality. Democracy under socialism is extended to industry and the community … and must involve a substantial decentralisation of power.”

There was a commitment to “political pluralism” and to “economic pluralism” involving “a variety of forms of common ownership … and the toleration of a small private sector including self-employed workers and other private firms.” The economy must be dominated by mechanisms of “democratic planning … but also accommodating a market mechanism in some areas.”

But there was strong hostility to these mildly revisionist ideas from within Labour’s ranks at the time, including from Jeremy Corbyn and Tony Benn.

Tony Benn & Jeremy Corbyn

The Guardian newspaper reported the LCC conference with the headline: “Labour breaks taboo on ownership”. For a while, the LCC tried to keep the conversation going on the need to revise Labour’s aims. The LCC held a conference in Liverpool in June 1984 on “The Socialist Vision”. But enthusiasm for this discussion fizzled out. By 1985 the LCC’s revisionist initiative had been kicked into the long grass. My efforts had failed.

But to their credit, Neil Kinnock and his deputy Roy Hattersley saw the need for Labour to modernise its aims. I advised them both for a while. But after 1987 I became less active in the Labour Party. My inactivity was born partly out of frustration that it was so difficult to shift Labour from its congenital hostility to markets and private enterprise.

But after a fourth election defeat in 1992 the party became more pliable. Tony Blair was elected as leader in 1994. Blair successfully changed the wording of Clause Four to endorse a strong private sector, but the dramatic rise of Corbyn in the party since 2015 shows that the old collectivist DNA has endured.

Towards liberalism

In many ways I have always been a liberal, especially in my support for freedom of expression, other human rights and democracy. By the late 1970s I also accepted the importance of markets and private property. But the emphasis in my thinking has shifted further in the last 30 years.

My academic works show a few markers of my political evolution. On page xvi of my 1999 book Economics and Utopia I wrote of my common ground with the US liberal John Dewey and with

“British social liberalism, which stretches from John Stuart Mill through Thomas H. Green to John A. Hobson, John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge.”

These thinkers still inspire me. But I would now also stress the importance of Thomas Paine. Other heroes include George Orwell and Arthur Koestler.

So by 1999 I was a true liberal, of social-democratic stripe. I had already moved some distance from the ideas in my 1984 book, which had over-stressed the possibilities for large-scale planning and for extensive democratic decision-making in large, complex economies.

But I still believe in judicious state intervention and regulation, and I am still an enthusiast for experiments with worker cooperatives and other forms of worker and community participation. With their lower levels of economic inequality, I see the Nordic countries as good role models for in the rest of the capitalist world.

From leaving Labour to joining the Liberal Democrats

In 2001 I left the Labour Party because of Blair’s energetic support for faith schools, Labour’s inadequate proposal for House of Lords reform and its neglect of the problem of economic inequality. I would have left over the Iraq War. Previously I had sometimes voted tactically for the Liberal Party, when they were second behind the Tories in my constituency. But what was tactical was also in growing part a matter of conviction.

I voted Liberal Democrat in the 1997, 2001, 2005 and 2010 general elections. But I did not approve of the coalition with the Tories. So the Liberal Democrats did not get my vote in 2015.

I re-entered political activity in 2016 after the Brexit referendum. My wife (Vinny Logan) had been a critical but close companion on my long journey since 1980. But unlike me she had always voted Labour. After the Brexit vote she joined the Liberal Democrats and I followed her after a few days. It will be a long hard slog to change British politics for the better, but it is vital that we try.

My wife and I were each brought up in a social culture where the Tories and the Establishment were the enemy, and the Liberals were seen as wishy-washy waverers in the class war. Labour was the only game in town.

It takes a long time to remove these ingrained preconceptions and learn that liberalism is the greatest legacy of the Enlightenment. It is the strongest guardian of both prosperity and freedom. Although Liberals have been in a minority, they are largely responsible for the foundation of the British welfare state. The NHS was originally a Liberal proposal. The Liberal Democrats constitute the most pro-EU party in the UK.

But some Liberal Democrats do not understand that it is the job of government in a recession to increase effective demand, particularly by increasing investment and raising disposable incomes for the poor. But the party is a broad church, and I will argue my corner in favour of Keynesian liberal economic policies.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

Today, both the Conservatives (now ruled by deceitful nationalists) and Labour (where the rising hard left dominate the timid moderates) are dangerous threats to the liberal and democratic rights and values that in the past we have taken too much for granted. We must now stand up to defend those rights and values, against dogma, ignorance, intolerance, petty nationalism and deceit.

20 September 2017

Minor edits – 25 September 2017, 22 October 2017, 10 April 2018.

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Foote, Geoffrey (1997) The Labour Party’s Political Thought: A History, 3rd edn. (London: Palgrave).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1975) Trotsky and Fatalistic Marxism (Nottingham: Spokesman).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1977) Socialism and Parliamentary Democracy (Nottingham: Spokesman).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1979) Socialist Economic Strategy (Leeds: Independent Labour Publications).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1981) Labour at the Crossroads: The Political and Economic Challenge to Labour Party in the 1980s (Oxford: Martin Robertson).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1984) The Democratic Economy: A New Look at Planning, Markets and Power (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (1999) Economics and Utopia: Why the Learning Economy is not the End of History (London and New York: Routledge).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Kornai, János (1965) ‘Mathematical Programming as a Tool of Socialist Economic Planning’, reprinted in Nove, Alec and Nuti, D. M. (eds) (1972) Socialist Economics (Harmondsworth: Penguin), pp. 475-488.

Nove, Alec (1980) ‘The Soviet Economy: Problems and Prospects’, New Left Review, no. 119, January-February, pp. 3-19.

Nove, Alec (1983) The Economics of Feasible Socialism (London: George Allen and Unwin).

Nove, Alec and Nuti, D. M. (eds) (1972) Socialist Economics (Harmondsworth: Penguin).

Posted in Bertrand Russell, Common ownership, Democracy, Jeremy Corbyn, Karl Marx, Khmer Rouge, Labour Party, Left politics, Liberalism, Ludwig von Mises, Mao Zedong, Markets, Nationalization, Private enterprise, Property, Right politics, Socialism, Soviet Union, Tony Benn

August 14th, 2017 by geoffhodgson1946

Geoffrey M. Hodgson

The world is full of injustice and poverty, while the rich protect their wealth by manipulating the system of power. Consequently, many of the informed and intelligent are lured like moths to the lights of socialist revolution, promising social justice for the many not the few.

Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was a blazing light in Russia a century ago. Many intellectuals were attracted to his Soviet regime. Lenin is said to have coined the term “useful idiot” to describe the naïve among them (but no evidence has been found to support that attribution).

But in 1913 Lenin definitely did quote the old adage that “the road to hell is paved with good intentions”. This was unwittingly self-referential and rather prophetic. Lenin’s post-1917 Bolshevik regime became a hell, in part of his own making. The good-intentioned (with sufficient means or influence) were invited from abroad to visit the young Soviet Republic.

Venezuela – “another world is possible”

But first let us consider the current case of Venezuela. Its experiment in radical socialism began in 1998 when Marxist Hugo Chávez was elected as President. Using the plentiful oil revenues during 1999-2007, his government expanded access to food, housing, healthcare, and education, especially for the poor and the indigenous minorities.

Hugo Chávez

Chávez nationalized key industries and created participatory Communal Councils. He whipped up popular support against the rich elite and their perceived allies in the United States. But constitutional checks and balances slowed down his radical reforms. Criticism from the private press and political opposition countered the populist movement.

So in 1999, the new Constitutional Assembly, filled with elected supporters of Chávez, drafted a new constitution that made censorship easier and granted the executive branch of government more power.

The Constitutional Assembly extended the presidential term. It abolished the two houses of Congress. It also granted Chávez the power to legislate on citizen rights, to promote military officers and to oversee economic and financial matters.

In 2002 Chávez was briefly deposed in a coup, which probably had support from the CIA. But Chávez was restored to power by the army and popular mobilisations.

Chávez then seized control of the courts and the electoral authority, and suppressed much of the opposition media. He removed political checks and balances, seeing them as obstacles to his socialist revolution.

Accordingly, the device of populist democracy was used to push the country in the direction of dictatorship. His supporters were persuaded to approve increases in presidential powers, to protect the “socialist revolution” against its enemies. Since 2004, “defamation” of the government, including “disrespect for the authorities”, has been a criminal offence.

Chávez failed to diversify the economy and reduce its reliance on oil. He antagonised private investors. The state-centred economy was not robust enough to withstand the post-2008 oil price collapse.

Venezuela’s descent into hell

In a state-run economy, business corruption is encouraged by bureaucratic failure. Political corruption is facilitated by the gathering of powers in the hands of the ruling party and the state machine. The Venezuelan government became one of the most corrupt in the world. Serious shortages of food and medicine emerged.

“There’s no food”

Chávez died of cancer in 2013 and was replaced as President by Nicolás Maduro.

In 2015 and 2016, blaming internal “fascists” and US intervention for the severe shortages, President Maduro declared two states of emergency. These gave him powers to intervene in the economy. Arbitrary detentions of dissidents became more common.

The regimes of Chávez and Maduro wasted and misspent much of the money made in the oil boom, while over-extending the powers of their corrupt governments. The private sector was hobbled. The ultimate outcome of Venezuela’s experiment with populist socialism has been authoritarianism, destitution and starvation.

Because of a populist mistrust of liberal, pluralist institutions, Venezuela is lurching toward dictatorship. Press freedom is limited and critical journalists and opposition leaders are jailed.

Supporters of Chávez and Maduro blame the hostility of the US for Venezuela’s distress, just as it was blamed for economic problems in Cuba after its 1959 revolution. US belligerence made things worse, and will probably continue to do so.

But the major cause of economic stagnation in Cuba and Venezuela is the unchecked concentration of excessive political, legal and economic power in the hands of the overbearing state.

Los idiotas útiles

Back in the UK, Jeremy Corbyn attended a 2013 vigil following the death of Chávez, hailing him as an “inspiration to all of us fighting back against austerity and neo-liberal economics in Europe”. As late as 2015, when Venezuela was in ever-deepening crisis, Corbyn’s enthusiasm for the regime was undiminished. He remarked:

“we celebrate, and it is a cause for celebration, the achievements of Venezuela, in jobs, in housing, in health, in education, but above all its role in the whole world … we recognise what they have achieved.”

Corbyn has since been challenged to come out against the hellish Maduro regime. Maduro’s government has been accused of arbitrary arrest, extra-judicial killings and torture.

Jeremy Corbyn and Hugo Chávez

Having managed to dupe many people with the mantra that he was a “peacemaker” in Northern Ireland (rather than a supporter of the IRA), Corbyn tried the same trick with Venezuela.

First he removed all mention of “Venezuela” from his website. Then, in an August 2017 interview, he condemned the “violence done by all sides”.

The Venezuelan opposition includes both rightist agitators and defenders of human rights. By simply condemning violence, Corbyn appeared as morally neutral between the regime and its diverse opponents. He ignored the politico-economic conditions that had given rise to the violence, and the previous actions of the Chavistas in creating them.

I wonder if Corbyn could be taken back in a time machine to the 1793-94 Terror of the French Revolution, or the Soviet Great Terror of the 1930s, or the occasion of Hitler’s invasion of the Sudetenland in 1938, and be asked to condemn with detached neutrality the “violence done by all sides”.

In the same interview Corbyn called for respect for “the independence of the judiciary and … the human rights of all”. He failed to note that Chávez and Maduro were primarily responsible for undermining both.

Questioned about his support for Maduro, Corbyn fudged:

“I gave the support of many people around the world for the principle of a government that was dedicated towards reducing inequality and improving the life chances of the poorest people.”

He omitted to mention that that same socialist Venezuelan government was now responsible for widespread starvation, rampant corruption and mass emigration.

But Jeremy of Islington is in search of socialist sainthood. He does not want the blood of any regime on his hands. He wants to go down as a peacemaker. He left it to his Corbynista Praetorian Guard to make a more forceful case for the Chávez-Maduro regime.

Over to the Corbynistas

Labour MP Chris Williamson tweeted on 11 August 2017 that the violence in Venezuela is “for the purpose of overthrowing democracy, not saving it”. Unlike Corbyn, this blamed all the violence on the opposition. It also overlooked the fact that Chávez and Maduro had been more effective in undermining democracy in Venezuela than anyone else.

Chris Williamson MP & Jeremy Corbyn MP

On the following day, Williamson Tweeted: “The US and global corporations are indulging in economic sabotage in Venezuela to bring down the government”. To a degree this may be true. But the statement ignores the greater part played by Chavista populism and its power-grabbing statist socialism in bringing about the economic and political catastrophe.

Other pro-Chavista idiotas útiles include Alexis Tsipras the Greek Prime Minister, Pablo Iglesias of Podemos in Spain, Jean-Luc Mélenchon the leftist French presidential candidate, Pope Francis and the Five-Star Movement in Italy.

The erosion of civil liberties and human rights has its roots in the concentration of economic and political powers in the hands of the state, whatever the “good intentions” that originally motivated the leaders and their supporters.

Stalin the Fabian and the Stalinist Fabians

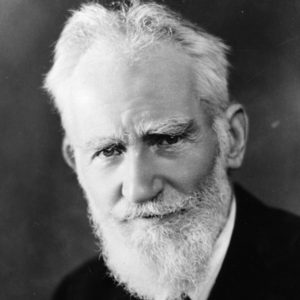

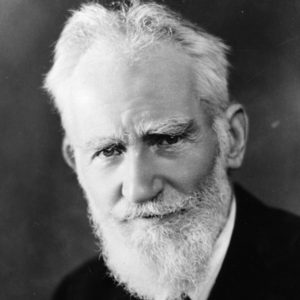

Sadly, this is an old pattern. The Fabian socialist George Bernard Shaw visited the Soviet Union in 1931 and met Joseph Stalin. Shaw declared that Russia was becoming “a Fabian society”. This was at a time of mass famine and forced collectivisation.

George Bernard Shaw

In the preface to his 1933 play On the Rocks, Shaw defended the Russian secret police’s “liquidation” of detainees who could not give satisfactory answers to queries about “pulling your weight in the social boat” or “giving more trouble than you are worth” or had not “earned the privilege of living in a civilized community”.

In a letter published in the Manchester Guardian in 1933, Shaw and others dismissed reports of famine in the Soviet Union as “slander” resulting from a “lie campaign” against the “Workers Republic of Russia”. In fact, from 1932 to 1933, about six to eight million people died there from hunger.

Shaw subsequently attempted to justify the extermination of the Russian peasantry: “For a Communist Utopia we need a population of Utopians. Peasants will not do.” In 1936 Shaw defended Stalin’s purges and mass executions. In 1948 he declared that Stalin was “a first rate Fabian”.

Beatrice & Sidney Webb

Leading Fabians Sidney and Beatrice Webb were highly influential intellectuals in the British Labour Party. In 1932 they made a three-week visit to the Soviet Union. Their generally favourable impressions were reported in 1935 in their massive two-volume study, Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation? In the 1937 edition the question mark was removed from the title.

Their assessments of the Soviet Union were more cautious than those of Shaw, but they also denied the existence of a famine in the Ukraine in 1932-1933 and they opined that the liquidation of rich peasants (kulaks) may have been necessary to collectivize agriculture and increase its productivity. Their book received favourable reviews from left writers and it played a role in nurturing sympathy in the Labour Party for the Soviet Union, at least until the onset of the Cold War in 1948.

“Humane” Mao and the “Korean miracle”

Communism achieved another victory when Mao Zedong came to power in China in 1949. Professor Joan Robinson was a leading Cambridge economist, influenced by both Karl Marx and John Maynard Keynes. An enthusiastic supporter of Mao, she visited China several times.

Despite this first-hand experience, she failed to acknowledge that Mao’s Great Leap Forward in 1958-1961 had been an economic disaster: it had led to catastrophic famine and about 40 million deaths. In defiance she wrote: “the Great Leap [Forward] was not a failure after all, but the Rightists were reluctant to admit it.”

Joan Robinson

In the 1960s Robinson lauded the Cultural Revolution, approving of attempts by Mao and the Red Guards to root out “capitalist roaders” within Chinese society. She praised Mao’s “moderate and humane” intentions. In fact, the Cultural Revolution led to at least half a million and perhaps as many as two million deaths.

Violent struggles ensued across the country and paralyzed the economy for years. Many more millions of people were persecuted at whim by the Red Guards: they suffered public humiliation, arbitrary imprisonment, torture or execution. Countless more died when the army tried to re-establish order. In China’s totalitarian system they had no refuge or legal protection.

As late as 1973 Robinson opposed “market socialism” and advocated a centrally-planned economy. She wrote of the “success of the Chinese economy in reducing the appeal of the money motive”. After extolling the virtues of Mao’s system, she reported that “Chinese patriotism and socialist ideology are pulling together”.

As late as 1973 Robinson opposed “market socialism” and advocated a centrally-planned economy. She wrote of the “success of the Chinese economy in reducing the appeal of the money motive”. After extolling the virtues of Mao’s system, she reported that “Chinese patriotism and socialist ideology are pulling together”.

But a few years later, shortly after Mao’s death in 1976, the country overturned the anti-market policies that Robinson had celebrated in her writings. After accepting markets, Chinese growth took off.

In 1964 Robinson visited Communist North Korea and extolled the “Korean miracle” in its economy. She attributed its claimed success to public ownership and central planning.

In 1964 Robinson visited Communist North Korea and extolled the “Korean miracle” in its economy. She attributed its claimed success to public ownership and central planning.

But, within fifteen years, capitalist South Korea was surging ahead of its Northern neighbour. By the 1990s North Korea was experiencing mass famines. By 2010, GDP per capita in the South was about 17 times greater than in the North.

The “human face” of Soviet Communism

E P Thompson

The historian Edward P. Thompson left the British Communist Party after the 1956 Hungarian Uprising and subsequently played a major part in the formation of the New Left Review. But as late as 1973 he had sufficient residual sentimentalism for the Soviet Union to write of the

“times when [Soviet] communism has shown a most human face, between 1917 and the early 1920s, and again from the battle of Stalingrad to 1946.”

Leszek Kolakowski

Leszek Kolakowski’s response to these rose-tinted words was devastating. He asked what Thompson might have meant by the “human face” of the Soviet Union during these years. Did it mean the “attempt to rule the entire economy by police and army, resulting in mass hunger with uncountable victims, in several hundred peasants” revolts, all drowned in blood”?

“Or do you mean the armed invasion of seven non-Russian countries which had formed their independent governments …? Or do you mean the dispersion by soldiers of the only democratically elected Parliament in Russian history …? The suppression by violence of all political parties, including socialist ones, the abolition of the non-Bolshevik press and, above all, the replacement of law with the absolute power of the party and its police in killing, torturing and imprisoning anybody they wanted? … And what is the most human face in 1942-46? Do you mean the deportation of eight entire nationalities of the Soviet Union with hundreds of thousands of victims … ? Do you mean sending to concentration camps hundreds of thousands of Soviet prisoners of war handed over by the Allies?”

Kolakowski searched for an explanation of Thompson’s incredible description of these events as “a most human face” of Communism. Perhaps this phrase is being used “in a very Thompsonian sense which I do not grasp”? A commentator on Kolakowski’s response wrote: “no one who reads it will ever take E. P. Thompson seriously again.”

Another “distortion”: the killing fields of Cambodia

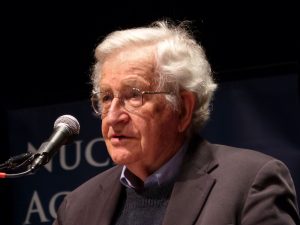

Robinson and Thompson were not the only top-rank academics to be deluded by ideology. Consider the most important linguist of the twentieth century. Noam Chomsky loathed the American war in Vietnam. For him, to hide its own acts of oppression and mass murder, the West had duped the masses with its slick corporate propaganda. The West was fascism, with a fake mask of democracy.

Noam Chomsky

But when reports emerged that the Communists were also capable of mass atrocities, he suspected an American conspiracy to exaggerate and to draw attention away from their own crimes. Then the evidence emerged of the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge in 1975-1979. Chomsky accused the publishers of the evidence of “extreme anti-Khmer Rouge distortions”.

Khmer Rouge Killing Fields

We now know that the Khmer Rouge obliterated about two million people – a quarter of the Cambodian population – in the pursuit of their Communist utopia. Chomsky’s reputation as a political thinker has never recovered.

Conclusion: what can we learn?

The first lesson is that thousands of highly intelligent people can be political idiots. We know that unintelligent people can be idiots (and even become presidents) but the task at hand is to explain intelligent idiocy. All it takes is a good dose of utopian idealism, combined with the view that the existing system is beyond reform.

Then when the likes of Lenin, or Mao, or Kim Il-sung, or Castro, or Pol Pot, or Chávez raise the red flag, the utopian intellectual flies to the light. A dose of reality may burn the wings. But the light of intellectual hope is so important that it must remained undimmed. Consequently, events as big as famines are based on the dark capitalist forces outside, or their devious agents within.

Many intellectuals are not practical people. They have lingered in their ivory towers. They know little of running organizations or state bureaucracies. Because of their well-motivated discontent and their search for hope, they can be attracted to Corbynism and other versions of leftist populism. But those lights are dangerous. They are ignited by opposition: without practical experience or feasible solutions.

Given such centralized powers, even well-motivated leaders will be tempted to curtail dissent and bully minority interests, in the name of the many against the few. Once on this slippery slope, human rights are eroded and the politico-economic system slides toward totalitarianism.

A lesson of the twentieth century is that classical socialism is a dead end. Viable democracies survive because there are countervailing, political and economic powers, which themselves depend upon mixed economies with large private sectors. Classical socialism unavoidably undermines the politico-economic foundations of democracy.

Instead we need to look to ways to making capitalism more egalitarian and inclusive, rather than chasing the dangerous dream of its abolition. Intelligent dreamers need to use their intelligence more wisely.

14 August 2017

Minor edits – 16, 20 August 2017, 27 September, 13 December 2017

This book elaborates on some of the political issues raised in this blog:

Published by University of Chicago Press in January 2018

Bibliography

Barsky, Robert F. (1997) Noam Chomsky: A Life of Dissent (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

Borger, Julian (2016) ‘Venezuela’s worsening economic crisis’, The Guardian, 22 June. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/22/venezuela-economic-crisis-guardian-briefing

Canning, Paul (2016) ‘Venezuela: The Left’s Giant Forgetting’. http://paulocanning.blogspot.co.uk/2016/09/venezuela-lefts-giant-forgetting.html

Cohen, Nick (2007) What’s Left? How the Left Lost its Way (London and New York: Harper). See pp. 157-68.

Cunliffe, Rachel (2016) ‘Corbyn looks the Other Way as Venezuela Self-Destructs’, 18 January, http://capx.co/corbyn-looks-the-other-way-as-venezuela-self-destructs/.

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2015) Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Hodgson, Geoffrey M. (2017) Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

Hollander, Paul (1998) Bernard Shaw: A Brief Biography (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press).

Jones, Bill (1977) The Russia Complex: The British Labour Party and the Soviet Union (Manchester: University of Manchester Press).

Judt, Tony (2006) ‘Goodbye to All That?’ New York Review of Books, 21 September 2006.

Kolakowski, Leszek (1974) ‘My Correct Views on Everything: A Rejoinder to Edward Thompson’s “Open Letter to Leszek Kolakowski”’, Socialist Register 11. See pp. 4-5. Available at http://socialistregister.com/index.php/srv/article/view/5323/2224#.VXBUKrFwYy8.

Minney, Rubeigh J. (1969) The Bogus Image of Bernard Shaw (London: Frewin).

Robinson, Joan (1969) The Cultural Revolution in China (Harmondsworth: Penguin). See pp. 19, 35-36.

Robinson, Joan (1973) Economic Management in China 1972 (London: Anglo-Chinese Educational Institute). See pp. 4, 13, 37.

Shaw, George Bernard (1934) Prefaces by Bernard Shaw (London: Odhams Press). See p. 341.

Staples-Butler, Jack (2017) “Starvation and Silence: The British Left and Moral Accountability for Venezuela”, 7 July. https://historyjack.com/2017/07/07/starvation-and-silence-british-left-and-venezuela/

Telesur (2015) ‘British MP Jeremy Corbyn speaks out for Venezuela’, 6 June. http://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/British-MP-Jeremy-Corbyn-Speaks-Out-For-Venezuela-20150605-0033.html.

Thompson, Edward P. (1973) ‘An Open Letter to Leszek Kolakowski’, Socialist Register 10. See p. 77, emphasis added. Accessible on http://socialistregister.com/index.php/srv/article/view/5351#.VXBrZLFwYy8.

Turner, Marjorie S. (1989) Joan Robinson and the Americans (Armonk NY: M. E. Sharpe). See p. 90.

Webb, Sidney J. and Webb, Beatrice (1935) Soviet Communism: A New Civilisation? (London: Longmans Green).

Posted in Common ownership, Democracy, E P Thompson, George Bernard Shaw, Jeremy Corbyn, Joan Robinson, Karl Marx, Khmer Rouge, Labour Party, Left politics, Lenin, Leszek Kolakowski, Mao Zedong, Markets, Nationalization, Noam Chomsky, Populism, Private enterprise, Socialism, Soviet Union, Venezuela

The consequence of this class deprivation of human rights was enshrined in law under Marxist-socialist regimes. The 1918 Constitution of the young Soviet regime distinguished between the rights of the workers and the rights of others. The Soviet state also announced that it

The consequence of this class deprivation of human rights was enshrined in law under Marxist-socialist regimes. The 1918 Constitution of the young Soviet regime distinguished between the rights of the workers and the rights of others. The Soviet state also announced that it

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

I was at the LSE student occupation in 1967 and one of the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in 1968. In that year I copied Bertrand Russell and tore up my Labour Party membership card in protest against US aggression in Vietnam.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

I am a radical liberal. I believe in social solidarity with the less-privileged, as well as in individual rights. As Charles Kennedy showed when he was leader, the Liberal Democrats can succeed when they take principled, radical positions on justice, equality and war.

As late as 1973 Robinson opposed “market socialism” and advocated a centrally-planned economy. She wrote of the “success of the Chinese economy in reducing the appeal of the money motive”. After extolling the virtues of Mao’s system, she reported that “Chinese patriotism and socialist ideology are pulling together”.

As late as 1973 Robinson opposed “market socialism” and advocated a centrally-planned economy. She wrote of the “success of the Chinese economy in reducing the appeal of the money motive”. After extolling the virtues of Mao’s system, she reported that “Chinese patriotism and socialist ideology are pulling together”. In 1964 Robinson visited Communist North Korea and extolled the “Korean miracle” in its economy. She attributed its claimed success to public ownership and central planning.

In 1964 Robinson visited Communist North Korea and extolled the “Korean miracle” in its economy. She attributed its claimed success to public ownership and central planning.